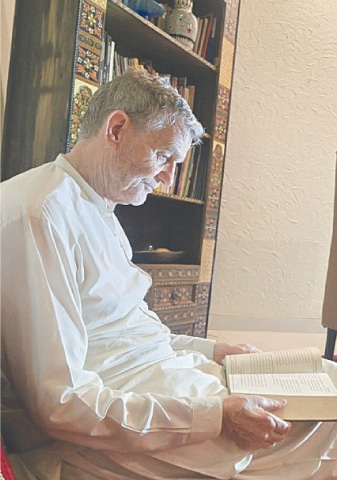

British scholar Dr Robert Sampson has dedicated his life to teaching and learning from Pakhtuns. An educational consultant in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Dr Sampson is a strong lover of the Pashto language and Pashto literature. He has also taught as an O- and A-Level science teacher at the Edwardes College Peshawar from 1989 to 2009.

Dr Sampson is known for his work on Pashto language and literature, particularly his translations of the Sufi poet Rahman Baba’s work. He has co-authored, with Momin Khan, a translation of Rahman Baba’s collected works. He has also written other books on Pashto language and culture, which includes a dictionary of spoken Pashto, Popular Pashto Proverbs, Reading Pakistani Pashto and Gauntlet, a novel in English based on the first Anglo-Afghan war, fought from 1838 to 1842.

B&A recently had a chance to speak to him. Following are excerpts from the interview.

What prompted you to explore Pashto and the Pakhtuns?

I had the joy to be offered to take a job at Edwardes College and School in 1989. I realised that, to work in the excellent context of the college [started in 1900], I needed to better understand my students. So the first day I gave them a ‘quiz’ about their families, their goals and their first language. It was clear to me from the start that I had better know how to communicate with my students in Pashto. Good teaching is a lot about respect — respect for the teacher by the students and the teacher’s respect for his students. Later, in 2009, I left Edwardes College Peshawar to pursue my projects on the Pashto language and Pakhtun culture.

What aspect of Pakhtun life impressed you and why?

I had taught in three different countries before coming to Peshawar. At first, it took me a little by surprise to have my students stand up when I came into the class. Now I understand the deep courtesy in Pakhtun culture. It means that seniors are seen in high esteem. I had arrived in a world where community and family counted. I reflect on the way my own four children were raised in the best of society.

Do you think the portrayal of Pakhtuns by orientalists is genuine?

When living in another country, the best orientalists feel a tenderness towards their new home. I am reminded of 1855, when Padre Hughes chose to help with those sick in the city with cholera. It was his character to genuinely care for those who were dying — while other foreigners moved out of Peshawar to avoid becoming sick.

Tell us about your first impressions about Pakhtuns?

When I first arrived in Peshawar in 1976, I stayed in the old Spogmai Hotel in the Old City. There was a feel, a delight in making conversation with Pakhtuns in the city. It is that initial impression that held me for more than 10 years, until when I was invited to teach in Peshawar. I also told my wife that the people in the area carried an enchantment.

Have reading and writing about Pakhtuns changed your perspective?

A lot has been written about the Pakhtuns but the tired stereotypes of violent extremism have ignored the affectionate and witty nature of a tribe who are far more likely to brandish a proverb than an AK-47. I’ve learned as much about hospitality and friendship from them, and this has enriched all my relationships in life.

What is your take on the thinking that the colonialists exploited Pakhtuns?

I love to take friends to the Old City for historical tours. You can still see the old 1923 fire brigade, the old dancing building [Peshawar Museum now]. One place I always make sure to visit during these tours is the spot in Qissa Khwani [bazaar] where the British soldiers machine-gunned the unarmed Khudai Khidmatagar protesters, in a massacre on April 23, 1930. There we can lament the history of the criminal behaviour of colonists. As an ordinary citizen, the only thing I have been able to personally do is meet some of the grandchildren of the Khudai Khidmatagar and say ‘sorry’.

Having lived among Pakhtuns for decades now, how would you define them as a community?

I have enjoyed the community feel in villages like Swat and Mardan. Staying with friends in the hujra provided me a glimpse into the powerful traditions that hold the community together. But maybe the Pakhtun community is in crisis, balancing tradition and modern lifestyles. Many Pakhtuns are moving to urban areas or abroad for work, leading to cultural transitions.

Why did you choose Rahman Baba for translation into English?

Every culture has a few deeply respected ‘superhero’ father figures. As soon as we listen to Rahman Baba’s amazing poetry, it is clear that his poems stand out from the other poets of his era. He has an uncanny power and his pithy turn of phrases make his poetry unique. Rahman Baba’s words have a fiery energy. His popular lines encourage us to be generous and sow flowers so that our surroundings turn into a garden instead of sowing thorns that will prick our feet.

What response did you get from the English-speaking community regarding your translation?

When my friend Momin Khan and I decided to try and translate the Diwan of Rahman Baba, we wondered if anyone would read the translation. But we were pleasantly surprised. After its first publication in 2005, the Diwan was republished in 2010. Besides, my other publications on Rahman Baba’s poems, such as Vision of Love [2012], have also remained popular. A most recent book, with Momin Khan and Ali Khan Yousafzai, Tuning the Heart: Best-Loved Pashto Poetry of Rahman Baba [2023] is also doing well. Our translations of Rahman Baba’s poetry have been used in an opera in Canada.

Would you like to divulge your current and future projects?

I am still learning new things about the Pakhtun language and culture. One area of interest I have not studied is the way landay [Pashto tapas] are used. I hope to publish a book on the popular landay, to help document the heritage of modern oral poems. Right now, more than 30 friends are doing a survey on around 3,500 landays, collected from different sources. We will see what we will learn.

I am encouraged that there is a push by the young. For example, a recent landay video by Gul Panra [a popular Pashto folk singer] on YouTube has been watched 26 million times. I have been privileged to enjoy the language, friendship and hospitality of the people. And I hope that others can see and understand the beautiful heart of the Pakhtun.

The interviewer is a Peshawar-based contributor.

X: @Shinwari_9

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, August 10th, 2025