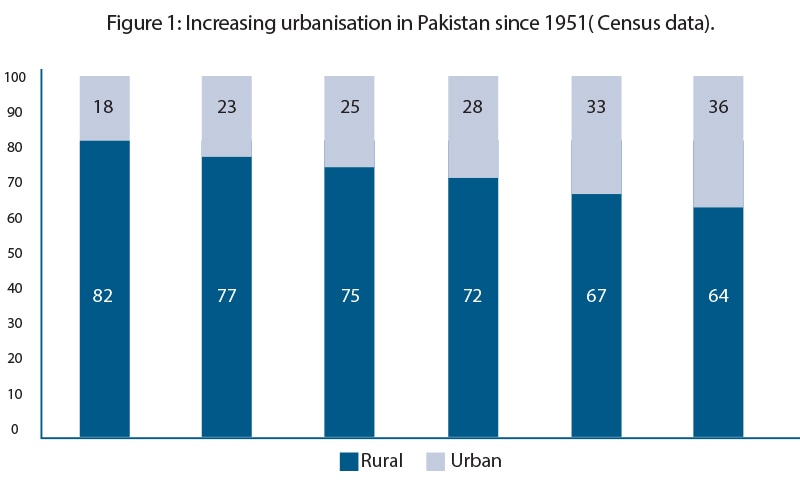

RURAL-urban migration and urbanisation are two sides of the same coin. The urban share of population in Pakistan more than doubled between 1951 and 2017; the years between the first and the most recent census (Figure 1). The rate of natural increase in urban areas in Pakistan was less than in rural areas and, therefore, increasing urbanisation was because of rural-urban migration.

Between 1998 and 2017, the years of the two most recent censuses, urban population increased by about 33 million and, based on the rates of natural increase in urban and rural areas, it is estimated that about 44pc of this increase was because of rural-urban migration. In other words, 14.5 million people migrated from rural to urban areas during this period; about 750,000 persons per year.

The census understates the level of urbanisation in most developing countries, primarily because the urban population in the census is for areas that are ‘administratively classified’ as urban, and the efficiency of local governments in reclassifying rural areas as urban is generally poor and varies across provinces.

The most glaring example in the 2017 census is that of Karachi. It seems to have grown on average by only 2.4pc per annum between 1998 and 2017, which is less than the average national population growth rate. If Karachi had grown at Pakistan’s average urban population growth rate of 4.4pc, its population in 2017 would be around 21 million.

Dr Navaid Hamid argues that although Pakistan’s urban population has spiralled, governments have failed to address the civic problems stemming from rapid urbanisation. An independent local government system is the only way forward.

In addition, ribbons of development along the highways in densely populated districts have been transforming the country’s landscape. For example, as you drive out of Lahore or any other major city, you see construction — including shopping malls, marriage halls, banks, hotels and restaurants — along the roadside for many miles. While these strips are not ‘administratively classified’ as urban, people living in them have access to health and education facilities, commerce and occupations similar to those in an urban area.

Development and urbanisation

In developed countries, the share of urban population has increased continuously for more than 300 years. At the beginning of the 18th century, urbanisation in Britain and western Europe was around 10pc, and by end of the 20th century it was 70-80pc in most developed countries.

South Asian countries are experiencing a similar process of urbanisation during the last 50 years (Figure 2). Bangladesh has had the fastest rate of urbanisation, while the pace of urbanisation in Pakistan and India remained similar until 1998, when the latter started urbanising at a faster rate. The rate of urbanisation in different countries and periods seems to be in line with the pace of economic growth in each country during that period, with Pakistan lagging behind on both counts.

Reasons for internal migration

An individual’s decision to migrate is motivated by pull and push factors. Higher incomes and better prospects in terms of access to health, education, infrastructure and jobs in urban areas — i.e. pull factors — are the main drivers of internal migration. The urban-rural gaps in income and social indicators are a measure of the pull factors, which are large in Pakistan.

For example, in urban areas, on average, income and literacy rates are 40-50pc higher and the gender gap in literacy, child and maternal mortality and poverty is 20-60pc lower than in rural areas (Figure 3). People in urban areas also attain significantly higher levels of education. Those in appropriate age groups having 12-years-or-more and 10-years-or-more education in urban areas is 75-120pc higher, and those who never attended school is 50pc lower than in rural areas (Figure 4).

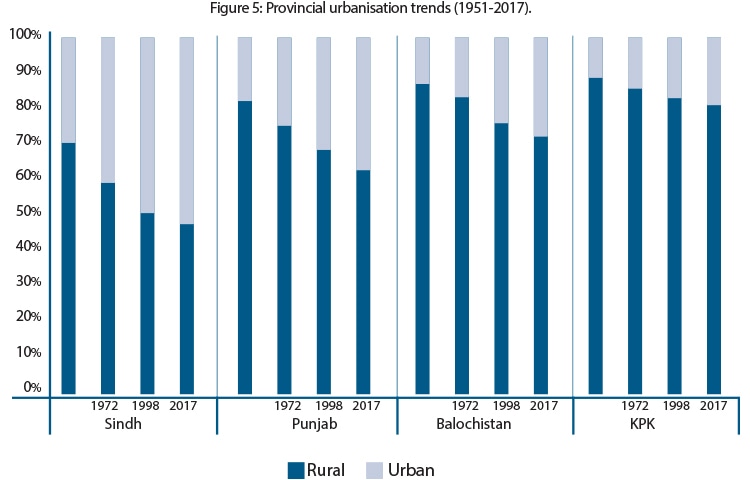

Patterns of urbanisation differ across the four provinces. Sindh was the most urbanised province in 1951 as it is today, with more than half the population residing in urban areas in 2017 (Figure 5). It seems that the rate of urbanisation in Sindh slowed considerably post-1998, but this is probably because of the underestimation of Karachi’s population and, adjusted for that, Sindh’s urbanisation rate is only slightly less than Punjab.

The rate of urbanisation has been most rapid in Balochistan, followed by Punjab, with the share of urban population in each province more than doubling during this period. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) had the slowest rate of urbanisation in the country in 2017. This is probably because of a combination of lack of industrial development and the readiness of the people to look for jobs and business opportunities outside the province.

The pattern of urbanisation in Sindh is unique, as one city, Karachi, dominates the urban landscape, with over 60pc (or 68pc, if adjusted for underestimation) of the urban population. In Punjab, Balochistan and KP, the urban population is much more evenly distributed with the largest city in each province, i.e. Lahore, Quetta and Peshawar, accounting for 27pc, 29pc and 34pc of the urban population of that province, respectively.

In Punjab, the next four largest cities (all with over a million population) account for 23pc of the urban population of that province, while the corresponding value in Balochistan and KP is about 20pc. Thus, in all the three provinces, about half of the urban population lives in medium and small cities.

Inter-provincial and external

Rural-urban migration within the province has been highest in Punjab (6pc), followed by KP (4pc), Sindh (3pc) and Balochistan (2pc). Inter-provincial migration in Pakistan has been quite limited: only 2.3pc of the population in Sindh, 1.5pc each in Punjab and Balochistan, and less than 0.5pc in KP were born in a different province.

Among the major cities, Islamabad has the largest proportion of migrants (36pc), followed by Lahore (15pc), while Karachi, Quetta and Peshawar are all about 12pc (Figure 6). However, almost 90pc of Lahore’s migrants came from within the province, while Karachi and Quetta attracted migrants from across the country, with 45-55pc of the migrants coming from a different province.

Pakistan has about nine million emigrants settled around the world and there are major differences in the provincial pattern of emigration. The proportion of the emigrants from Punjab is about the same as its share in the population, but the proportion of emigrants from KP is about two-and-a-half times its population share, while for Sindh it is less than half its population share (Figure 7). The high emigration rate in KP is probably because of the lack of decent employment opportunities within the province and historical tradition of long-distance migration.

It is estimated that 14.5 million people migrated from rural to urban areas within Pakistan during between 1998 and 2017, and, if we assume that two-third of the people who reside outside Pakistan emigrated during the same period, we can conclude that over 20 million people migrated during that period. Of these, 70pc migrated within the country and 30pc moved abroad. Thus, if it were not for external migration, urbanisation in Pakistan today would have been much higher, particularly in KP.

The share of urban population in Pakistan has more than doubled in the last 75 years and it is likely to at least double again by the end of this century. Rural-urban migration could accelerate in the coming years because the impact of global warming on water availability and agriculture production will push those in the worst affected communities to migrate to the cities.

However, urbanisation can be good because, by concentrating population and economic activity in a geographical area, it yields benefits in terms of increased productivity and higher standards of living. But to realise these benefits fully, it is important to address the problems associated with urbanisation. So far, Pakistan has failed to do so.

Most of our cities have poor basic urban services, such as clean water supply, sewerage system, solid waste management and public transport. In addition, our cities suffer from urban sprawl, traffic congestion, air pollution and a lack of low-cost housing. To make our cities more liveable and become engines of growth, we need to empower local governments and make them financially independent and accountable to their residents.

Dr. Naved Hamid is director CREB and a professor at the Lahore School of Economics. Ms Hijab Waheed is a teaching and research fellow at Lahore School of Economics.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.