City of Intellect: The Uses and Abuses of the University

By Nicholas B. Dirks

Cambridge University Press

ISBN: 978-1009394468

275pp.

Nicholas Dirks was the 10th Chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley (2013-2017). He decided to step down in only the fourth year of his chancellorship. The four years had been tough on him, as well as his family.

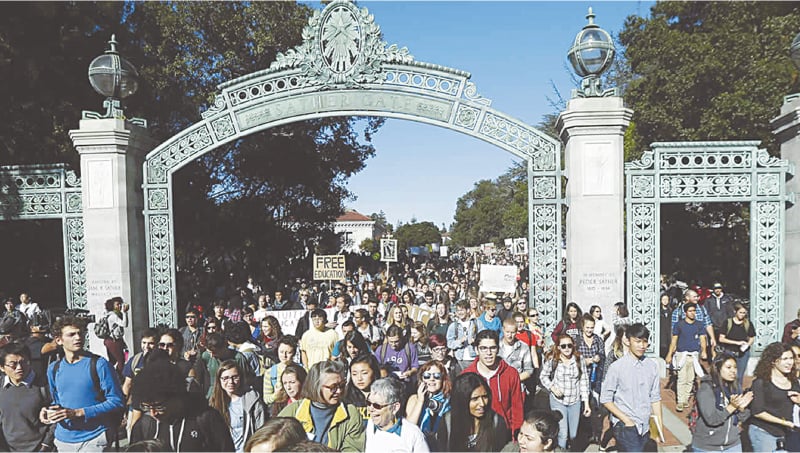

During the four years, Berkeley faced many challenging situations. There were protests around football and the status of intercollegiate sports, sexual assault and harassment, tuition fee increases and student debt, free speech and the felt need to combat hate speech, as well as budget shortfalls and consequent financial challenges.

Each of these issues came to the table of the chancellor, and each of them, though addressed, could never have been addressed to the satisfaction of all. And each of them took a heavy toll on Dirks, the trust in his leadership, his support as well as the social capital that he retained. After three years, Nicholas Dirks announced he would step down at the end of his fourth year.

His book, City of Intellect: The Uses and Abuses of the University, is part memoir, part history and part analysis of the situation that many of today’s universities find themselves in, and not just in the United States. It also includes some thinking around what issues need to be addressed to ensure the survival of the city of intellect.

A former faculty member and administrator of prestigious universities pens a book that is part memoir, part history and part analysis of the situation that many of today’s universities find themselves in, and not just in the United States…

Dirks took five to six years after stepping down to come up with this book. It has value as a memoir alone as well, but it is really the discussion around the issues universities face and what needs to be done that makes the book compelling.

By 2016-17, Dirks felt “Everyday life was weaponised and politics became polarised in ways that elicited fears that the country was headed for a civil war.” UC Berkeley has had a long history of protests. A lot of these came to a head over these years and to the point where Dirks felt that, if some of the underlying issues in higher education were not addressed, the survival of universities as cities of intellect, at least in the forms we know of, might not be possible.

Academia was home for Dirks. His father was also an academic. Dirks decided to be an academic quite early on as well. He went to some of the best institutions for his education (BA from Wesleyan University and MA and PhD from the University of Chicago), became a historical anthropologist and then worked at the California Institute of Technology, the University of Michigan and Columbia University (where he was chair of a department and then a dean), and finally came to UC Berkeley as the chancellor.

He understood the university inside out and had been a faculty member for a long time before becoming an administrator. But he was still surprised by the gulf that existed between being a faculty and being an administrator.

“Administrators have to conduct the complex balancing act of negotiating competing interests, values and choices in order to facilitate the smooth functioning of the university community, not always a recipe for purity or harmony,” he writes. “Intellectuals may think purity is available, but it can easily become an alibi for abdicating responsibility for one’s implication in institutional life. The desire for purity drives a wedge between many faculty and administrators. When talking about the university, the administrator attempts to explain institutional constraints, whereas most faculty tend to hold themselves aloof from their institutions while strongly criticising them.”

Dirks gives a nice quote from American historian and public intellectual Richard Hofstadter to make the point more strongly: “The characteristic intellectual failure of the critic of power is a lack of understanding of the limitations under which power is exercised. His characteristic moral failure lies in an excessive concern with his own purity; but purity of a sort is easily had where responsibilities are not assumed.”

If the right wing invites to the campus a speaker who represents the extreme of the right wing, and many other groups on campus oppose the coming of this person, and there is likely to be confrontation amongst the groups if the talk is held, what should the administrator do? When Dirks allowed such a speaker to come, he was criticised by all of the non-right wing groups. Despite all precautions, there was violence too, and he got blamed for that too. The accusation was that he had allowed hate speech.

At another point, when a talk got cancelled, he was blamed for imposing restrictions on constitutional rights to free speech. What is the balance here? There might be more of delineation possible on things said in class, as they have to be related to what is taught in class, but outside of class, where the university is seen as a place where debate can happen, the balance is harder to find.

Dirks’ own academic work was interdisciplinary: history and anthropology. And he was also involved, as faculty, in encouraging more interdisciplinary work at the graduate level, at both Michigan and Columbia. But it was when he became dean at Columbia and later when he was chancellor that he fully realised how difficult it was, as administrator, to have a dialogue with faculty on change and interdisciplinarity.

Change can be rejected for numerous reasons: that it is driven by commercial interests, market forces, budgetary constraints or fiscal austerity. The suspicions and lack of trust between faculty and administrators, Dirks found to be high and quite counterproductive.

UC Berkeley is a public university. When California was cutting down university funding significantly, and tuition fee increases were not allowed, administrators had to find ways to make ends meet while also protecting the core functions of the university and the pre-eminent position of Berkeley.

But the suspicions between all stakeholders — faculty, students, board as well as state officials — against each other, but especially against the administrators whose duty it was to ensure the changes, made the job all but impossible. Dirks was able to achieve a few things, but they were not even close to what he had wanted to achieve, and it took so much out of him that he decided to step down only three years into his chancellorship.

Though the story revolves around Dr Dirks’ own experiences at Columbia and Berkeley, it has relevance to the higher education sector in general, and across countries. Look at the public universities in Pakistan. Funding cuts have been severe while provincial and federal governments have been opening new universities. The older ones are having trouble meeting salary and pension obligations, while they are not allowed to increase tuition fees by much, and their ability to raise private funding, for operational, project or even endowment purposes, is just not there. And some of the same questions, about trade-offs between scale and quality, have been present in our discourse as well.

Nicholas Dirks believes that universities have a crucial and important role to play as cities of intellect. But, in changing circumstances (changes in markets, finance, technology, information, knowledge, jobs, careers, politics... you name it), the university has to change as well. And this can only happen if the various stakeholders within the university — administrators, staff, faculty, students and the community members involved — find ways of having dialogue with each other, and find ways of working with each other.

There will inevitably be disagreements and strong ones at that, but if dialogue can happen and there is willingness to change and address issues, universities could survive as cities of intellect. If they cannot, the survival of universities, as we know them currently, might not be easy.

This is definitely a book worth reading for people interested in higher education, and not just for the discussion on politics and realities of change. Nicholas Dirks’ experience and firsthand knowledge of the challenges confronting universities makes the narrative much more interesting and readable.

The second part of the book, more focused on issues in higher education, is more intense. But the discussion is quite rich and substantial. Again, for people thinking of education in general and higher education in particular, Dirks’ analysis, as well as his look towards the future, would be of value.

The reviewer is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives and an associate professor of economics at LUMS

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, June 1st, 2025