Rashida lives with her family in a dirty, polluted area. Rats have begun to proliferate in the waterways, largely because of food remains discarded by nearby hotels.

Out on the streets, there are just too many people.

“When school finishes,” Rashida says, “there is such a rush and so much noise, people taking selfies ... it is hard to walk home. There is no space to move. We have to hold on tight to our children. There are just so many strangers everywhere.”

Tourism tends to be seen as a panacea for economic ills but it can have terrible fallouts for local communities

Rashida is a schoolteacher in Murree, a tourist-friendly hill station north-east of Islamabad.

Just a 1.5-hour drive away from the capital, Murree is a popular and quick getaway for long weekends for domestic travellers. This year on Eid-ul-Fitr, around 111,000 vehicles reportedly visited the area. Murree’s economy is almost entirely fuelled by tourism, generating revenue and creating thousands of jobs each year, but all at the expense of disrupting the daily lives of the residents there. The advent of tourism brought numerous problems for the locals, says Rashida, but people who run businesses welcomed it.

Almost universally, the thrust of tourism projects is on reordering local landscapes and cityscapes to suit the touristic imagination while ignoring the lived reality of the area for its inhabitants. This often means that the local infrastructure of schooling, medical facilities, energy provision and garbage removal, which affects the daily lives of communities, is not improved and the focus of development remains on creating entertainment for tourists.

While major tourist spots, such as Murree’s Mall Road, are kept clean, behind the buildings on the road, piles of garbage fester and filth and untreated sewage flows into streams and groundwater. Water pollution has become a serious problem for the inhabitants. In the recent monsoon season, Rashida had to buy bottled water for her family because of apprehensions about drinking water being unsafe for consumption.

Women and children living in Murree, in particular, have reduced mobility because of the hordes of strangers on the streets. Frequently, locals are not even able to access the entertainment or facilities provided for tourists, because they cannot afford them, or access is denied to them. They lack access to entertainment facilities within their own localities. Rashida recounts taking her children and visiting family members on a rare trip to a local picnic spot, but coming back disappointed because the area was clogged with tourist traffic.

In fact, Murree exemplifies the problems that result from large-scale tourism. Locals cite rapid urbanisation as the primary cause for deforestation in the area. In just the last 19 years, Murree’s constructed area has increased by around 22 percent, resulting in deforestation, rising temperatures and severe water shortages as levels of groundwater have fallen, according to a research paper on water policy by IWA Publishing. Many buildings sprang up to serve the needs of tourists and, at the same time, led to the area’s dwindling forest cover.

Increasing domestic tourism in the mountain valley of Hunza in Gilgit-Baltistan also raises concerns that the area will face the same ecological degradation that has occurred in Murree. The manner of growth of local business and unplanned urbanisation reveals the state’s neglect of local needs while tourist agendas are prioritised. Architect Sabuhi Essa, a native of Hunza’s Karimabad area, says, “Tourist business returns have blinded people to the long-term outcome of a massive growth of tourism.”

When communities enter the race for cash and abandon practices of agriculture that previously gave them a measure of independence, corruption and conflict inevitably follow. Essa says, “We never imagined that the people of Hunza, who are so well educated, would act so recklessly. Unmindful of the harm to the environment, they are building shoddy hotels.”

Frequently visited by international tourists before 9/11, Hunza has already experienced the impact of tourism on its society and culture. According to Essa, the locals in Karimabad largely abandoned their primary livelihoods and farming practices as their dependence on tourism increased. In Murree too, as in other places exploited for the tourist industry, locals have abandoned farming and are now caught in a bind. Wasif, a grocery store owner in Murree, says, “People used to grow their own food, wheat and other things in Murree, but no one can do this anymore.”

Zaheer Khan, a resident of Gilgit, another scenic spot in the north, has a pragmatic outlook on how tourism has changed the area. The growth of domestic tourism has created new possibilities for livelihood for countless households, he says. Khan points out, “The tourist season only lasts for four months but if people earn well in summer, they can get through the winter months comfortably.”

The downside, he concedes, is that the growth of the industry is unmonitored and unregulated. This leads to haphazard construction of hotels and entertainment spots in the scenic areas. As more and more tourists are drawn to these areas, the amount of garbage irresponsibly left behind by them grows more and more, marring the pristine views and environment.

According to Essa, Karimabad’s social fabric too has changed irreversibly because of the tourism industry.

Post 9/11, Gilgit and Hunza faced a tourist drought. International tourists became wary of travelling to Pakistan as the country was viewed as dangerous. As Hunza was left deserted, young and educated Hunzais, who could not return to the pre-9/11 lifestyle, preferred moving out of Hunza in search of opportunities. Hence, the wave of tourism has been a major factor contributing to a diaspora and the unravelling of communal ties. “I feel overwhelmed walking on the streets in my own hometown which is full of strangers,” Essa says.

In some instances, the impact of tourism in the long run has tarnished the original charm and economic prosperity of a place.

Tourism engenders a drive to upgrade or gentrify places, making them more suitable for visitors by cleansing them of ‘undesirable elements’ (including, at times, the people who have populated that space previously) and carrying out a process of restoration and improvement. Ultimately, it excludes the poorer people. Examples of tourism-related gentrification abound globally. In the Caribbean Island of Antigua, for instance, waterfront development aimed at enticing cruise ship passengers to spend money has displaced people from their homes, as well as businesses and recreational spaces where young people previously played sports.

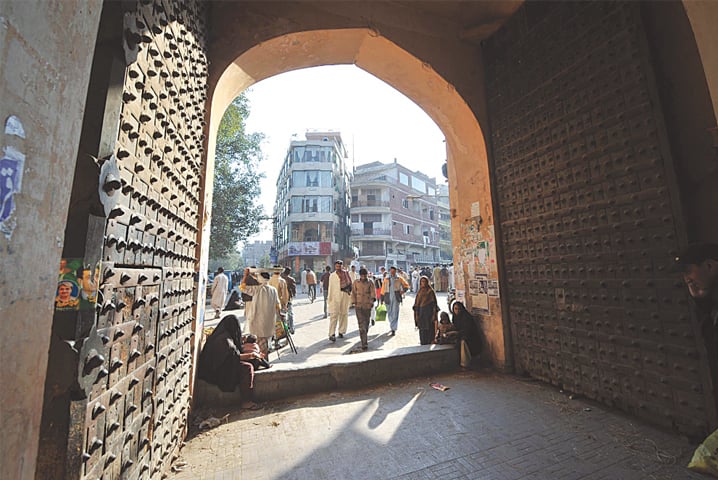

Looking closer at home, in Lahore’s walled city, residents describe the Fort Road food street as “ameeron ki jaga [a place for the rich].” Buying dinner for a family at one of the high-end restaurants costs as much as a month’s salary for a working-class person. Older residents wax nostalgic of the past when access was easy to the nearby monuments and Minto Park for morning walks before the development of the area for tourism.

Women and children living in Murree, in particular, have reduced mobility because of the hordes of strangers on the streets. Frequently, locals are not even able to access the entertainment or facilities provided for tourists, because they cannot afford them, or access is denied to them.

Despite growing tourism in the cultural heritage site of Lahore’s walled city, many residents of the area have experienced loss of independent livelihoods. As a project of heritage conservation, the well-designed interventions along the historical Shahi Guzargah or ‘Royal Trail’ inside Delhi Gate are commendable. Planners and authorities believed that the project would create economic well-being for the entire area. But most businesses catering to the increased flow of tourists — such as restaurants, tour operators, guides and photographers — and making the most profits are not run by residents.

“Yeh sub surkhi powder hai [All this is just cosmetic improvement]” is a common refrain one hears from the mostly poor residents as they struggle with unemployment, inflation and the cost of electricity bills. Vendors and shopkeepers have relocated or lost businesses both in the process and aftermath of the development of the Mughal era trail inside Delhi Gate. One of the vendors removed from the gate entrance remarks, “Hum arsh say farsh par aagaye hain [We have been left destitute].”

A recent article on Dawn.com posited that if Pakistan made exceptional advances in tourism, the possible gains to GDP could be in the region of $3.5 billion. Despite the potential benefits tourism holds for our economy, these are purely utilitarian calculations that do not take into account the idea of social justice. In a world that has changed irrevocably, there seems to be no going back to old practices for most communities — partly because this is what the communities belonging to cash-poor populations have also chosen for themselves. Economics provides careful cost-benefit analyses but it does not treat pollution, threats to privacy and the disruption of life as costs because many of these side effects of tourism are not easily measurable.

Global lessons from places which have experienced the often irreparable fallout of tourism demand that we go beyond advising caution. Tourism will only work as a long-term strategy if strong programmes for the uplift of local communities and the conservation and renewal of natural resources, such as forests, run in tandem.

“Murree ka husn khatm ho gaya hai [Murree has lost its beauty]” says Wasif. Some locals observe that tourism has declined slightly in the last two years (except on Eids), partly because of Murree’s degraded environment. As a consequence, tourists have begun to head to cleaner and greener resorts. This is potentially a worrying situation for people like Wasif, whose earnings depend mainly on tourism.

States and communities worldwide are designing programmes for ecotourism or cultural tourism but the results are mixed. Attempts at curbing the excesses of tourism require an independent state policy guided by the interests of people, local culture and the environment.

The state is obligated to improve the lives of the locals by focusing not only on projects that will provide facilities and entertainment to tourists, but to carry out structural improvements which will bring long-term benefits to the people of the area independent of tourism. Income flowing from tourism into the area does not absolve the state of its responsibility to every community and habitat in the country.

Zaheer Khan relates “the horror” of driving through Babusar Pass. The magnificent glaciers are littered with used diapers and plastic debris. These are the signs of tourists now visible in all areas in Pakistan frequented by tourists. Gilgit, which is already struggling to regulate its internal traffic, was “choked” in the summer with tourist traffic. While he is optimistic about the opportunities that tourism holds for Gilgit, Khan urges the government to strictly regulate tourism, particularly with regard to the construction and protection of natural habitat. Even if communities benefit economically, the onus remains upon governments to develop areas not only to facilitate tourists but to improve local lives.

Anika Khan is a faculty member at the Centre of Biomedical Ethics and Culture, SIUT, Karachi with an interest in education and environmental issues

Rabia Nadir is an assistant professor at the Lahore School of Economics, Lahore who is involved in research related to urban environments and conservation of architectural heritage

Published in Dawn, EOS, October 20th, 2019