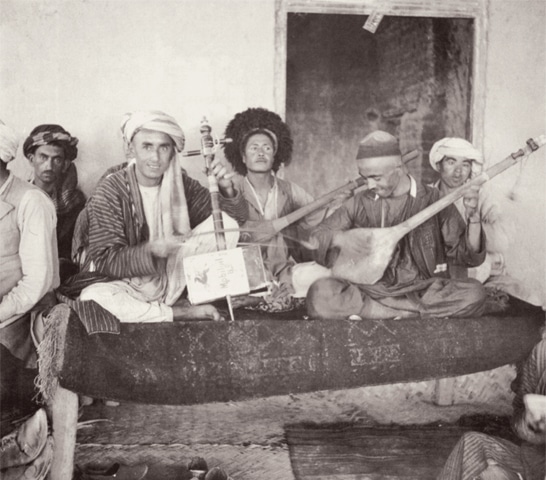

Tea is an important part of my life, particularly while travelling. On solo journeys, it gives me a reason to stop, take a break and observe life as it unfolds. In his book, A Thousand Cups of Tea, author Jürgen Wasim Frembgen writes, “Tea is a quiet drink, to feel well, enjoy something or to daydream.” As an avid tea-drinker I thoroughly enjoyed the book; it is an ideal read for any chai lover in Pakistan and anyone interested in understanding the consumption of tea in the Muslim world. The book also has some interesting photos showcasing historical teahouses, as well as the author’s observations on how tea is consumed by people in different parts of the world.

Composed in two parts, the first section comprises the history of tea, with an anthropological overview of the beverage and its consumption. The second part is a kind of travelogue that starts from North Africa and goes all the way to South Asia.

Frembgen begins his historical account with the origins of the drink in the southern parts of China from the third century BC. Initially drunk only by the elite and the rulers, tea became a public drink much later and was distributed by trade caravans as a medicinal beverage. Frembgen shares that in China, bricks of pressed tea leaves were used as a means of payment during trade, and in the Buddhist tradition tea had a religious significance as monks drank it to stay awake during meditations; such minute historical details make for very interesting reading.

In 2016, I was exploring organic tea gardens in the southeast of Nepal. Surrounded by lush green plantations in Ilam, I spent a week at the house of one of the farmers and was served freshly brewed black tea throughout. One day I asked my host if I could have tea with milk, to which he laughed and replied, “We were never under the influence of the British imperialists, hence we don’t spoil our tea with milk.” It was only then that I thought about the obsession of having tea with milk in Pakistan and India, which we call doodh patti or, as the author writes, “Milk tea, the real Pakistani chai.” Frembgen’s beautiful narration of how British imperialists aggressively marketed milk tea in the late 19th century in the region, promoting consumption through the capitalistic system of exploitation, is in a similar vein.

I found the second half of the book, the travelogue, particularly enjoyable. Frembgen takes readers on a journey beginning from North Africa, leading to the Middle East and ending in South Asia. Small descriptions add details to the places, constructing local context that helps readers visualise such things as the interior of the cafes, decorative motifs on walls, placement of tables, carpets, teapots and gardens etc. Along with describing the spaces in which tea was drunk, the author sketches out the people who were an important part of teahouses, such as storytellers who would entertain patrons with folklore as they sat sipping their cups of tea.

Again, Frembgen sprinkles his narrative with details that hooked me throughout, such as the Turkish practice of placing sugar under one’s tongue while sipping bitter tea, the cultural mores of Afghan teahouses where refusing tea is considered a great insult to the host, and that turning your glass upside down was a message to the host that you did not want any more. I was also greatly surprised to read about the observations made by Swiss anthropologists Alain and Micheline Delapraz during the 1950s that, in some parts of Afghanistan, carpets were washed in tea to make them appear older than they actually were.

However, in some places I felt that cultural sensitivities were not taken into consideration, or were lost in translation. For instance, the author mentions people in Punjab ordering tea “rudely” in their colloquial language, referring to Punjabi as a common language and generalising that customers in the region would ask for tea impolitely. In another place, I felt it was rather less anthropological and more of a Westerner’s observation of the East when the author refers to a person having tea in a café in Iran as “poorly dressed,” without providing any additional or further details.

Being a photographer myself, I was disappointed with the low resolution and poor composition of some of the photographs. The choice of words in the captions could also have been improved; for instance, the caption for one portrait of a smiling girl reads: “After tea in the mood of happiness and contentment”, implying that tea is the only solution to happiness and contentment.

At some places I felt more information was needed. For example, the tea consumption habits of people in the north and northwest mountains of Pakistan — where they prefer to drink it with salt instead of sugar — were not explained in detail. The write-up on Kashmiri chai was also far too short compared to the other write-ups; the author talks about Kashmiri chai through an encounter with a Kashmiri cook in Lahore, rather than the cafes or habits of people in Kashmir itself. While talking about South Asian inclinations, the author writes, “Most men in Pakistan and India prefer stronger tea, and most women prefer milder tea”, without explaining ‘why’ or any reasons behind such a choice.

If the author decides to write another edition, I would love to read more about the latest developments in tea culture, particularly in Karachi where high-end chai places — decorated with beautiful murals and offering space to play board games — are opening up. At such places, a cup might cost three times as much as it would in a regular teahouse, but here women and families can be accommodated in an open environment as opposed to regular chai khaanas that are usually dominated by men only. However, Frembgen does end his book with a discussion on various internet blogs and websites that are named after tea and are spaces for political and social discussion. As he points out, “drinking tea is a catalyst of conversations.”

As not a lot is written about tea culture, particularly that of Pakistan, this book is strongly recommended. As well as being a good compilation of tea consumption habits in the Muslim world, it also includes several interesting references to poets, films and books related to tea.

The reviewer is a travel writer and photographer

A Thousand Cups of Tea: Among Tea Lovers in

Pakistan and Elsewhere in the Muslim World

By Jürgen Wasim Frembgen

Translated by Jane Ripken

Oxford University Press, Karachi

ISBN: 978-0199406678

108pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, March 4th, 2018