LESS than a month remains for the five-year term of the present National Assembly and two provincial assemblies to end, after which elections have to be held within 60 or 90 days. But there is no dearth of sceptics who doubt that elections to the five assemblies, including those of Punjab and KP, which were dissolved in January this year, will take place according to the constitutional timeline.

This scepticism emanates from two possible sources. The Constitution requires that the election to the two dissolved provincial assemblies (Punjab and KP) be conducted within 90 days of dissolution. But the election was not held.

Both the Election Commission of Pakistan and the federal government refused to hold polls within that timeframe on more than one pretext. Even though the Supreme Court overruled the ECP timetable for holding these elections on Oct 8, and instead, directed the electoral body to conduct the Punjab Assembly election on May 14, the order was not implemented.

The National Assembly refused to approve funds for the election and the security agencies remained ambivalent about providing security personnel demanded by the ECP.

It is true that one of the key reasons for this non-compliance with Supreme Court directions and constitutional requirements was that both the ECP and federal government felt, and later expressed, that the scattered election of the five assemblies in the presence of caretaker governments in only two provinces, while a partisan government continued to rule the federation, was a recipe for unfair polls, whose results would not be accepted by the losing parties.

Despite these arguments, a sizeable body of voters remained convinced that elections in the two provinces were not held out of partisan considerations, as the PTI appeared likely to win. Public confidence that there would be strict compliance with the constitutional requirements of election dates has been shaken.

The second reason why the public is sceptical about the timely conduct of the election has something to do with our electoral history. In the past 10 instances, since the first direct national election in 1970, none of the winning political parties was allowed to assume (1970) or return to power in the subsequent election after it was removed or fell out of favour with the powers that be.

It seems that uncertainty will continue until elections are actually held.

Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, the undisputed winner of the 1970 poll, with 53 per cent of the National Assembly seats won by his party, was not allowed to assume power.

Even the Assembly was not allowed to meet because Mujib’s idea of the new constitution did not meet with the approval of Gen Yahya Khan, the president and chief martial law administrator, and West Pakistan leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Prime minister Mohammad Khan Junejo, who was appointed by Gen Ziaul Haq following the 1985 election, was dismissed after he justifiably began to assert his independence. Although the Supreme Court declared Junejo’s dismissal unlawful, he was not reinstated because, according to the court, fresh elections had been announced.

Benazir Bhutto, who was elected prime minister in 1988, was dismissed in about two years and she lost the subsequent election in 1990. Nawaz Sharif who became prime minister, heading the IJI alliance, met the same fate as Benazir Bhutto in 1993. Benazir Bhutto was able to win the 1993 election but was sacked in 1996.

The performance of her party, the PPP, in the 1997 poll was among the worst. Nawaz Sharif won the election with a two-third majority — a rare feat in Pakistan. However, he was not only dismissed but faced imprisonment and exile after the 1999 military coup. He and his party had to wait 14 years to return to power in 2013.

Even the PML-Q, headed by Chaudhry Shujaat Husain, which came to power in 2002 through the support of Gen Pervez Musharraf, failed to win in the 2008 poll. He accused Musharraf of manipulating the 2008 election to facilitate the PPP’s victory.

This electoral history of winning and losing has set a pattern. Gen Zia’s postponement of elections for eight years in order to deny victory to the PPP is part of that pattern.

In 2018, Imran Khan won the election, becoming prime minister. All was fine until he started asserting his authority beyond a certain red line. He was removed through a vote of no confidence in April 2022. He is perceived to have enhanced his popular appeal after he was voted out while his relations with the military worsened.

Today, he may be described as a party chief with one of the tensest ties with the military. Although efforts are afoot to make sure that he personally is not able to contest the next polls, and his party has been weakened through mass desertions, the project to remove him and the PTI from the electoral scene is nowhere near completion.

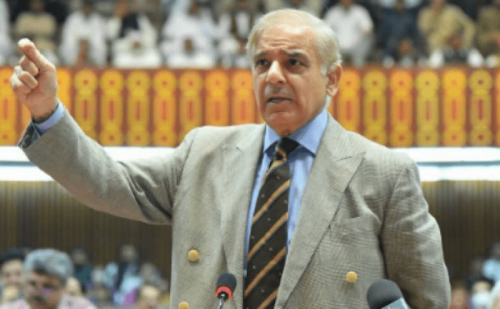

Experienced poll watchers and many voters feel, with their knowledge of our electoral history, that unless Khan is removed from the electoral scene altogether, the election cannot be guaranteed, despite the fact that Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif has categorically announced that his government would complete its term by mid-August, and other allies, including the PPP and JUI-F, have supported the holding of elections on time.

The questions about demarcation of constituencies based on census 2023 are also contributing to the uncertainty about the next election. The latest census was undertaken four years ahead of schedule so that election 2023 could be based on the new census as many parties including the PPP and MQM had expressed reservations about the results of census 2017.

Now it is not possible to undertake the fresh demarcation of constituencies based on census 2023 because the National Assembly doesn’t have the required strength to amend Article 51(3) of the Constitution which is a prerequisite for the fresh demarcation of constituencies.

It seems that uncertainty will continue until elections are actually held. That won’t be enough though; it has to be a free and fair electoral exercise.

The writer is president of the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency.

Twitter: @ABMPildat

Published in Dawn, July 17th, 2023

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.