Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib and Allama Muhammad Iqbal in a more regional context, and William Shakespeare in a more global one, would be turning in their graves in this era of social media. So many of the couplets and verses attributed to them were never written by them. But more than any of these greats, it is the words of Rumi — or not, actually, the words of Rumi — that are shared callously and confidently. Translations of alleged excerpts from the Masnavi-i-Masnavi of the 13th century poet, jurist, Islamic scholar, theologian and Sufi mystic Jalaluddin Muhammad Rumi — often called Maulana when mentioned with a term of endearment — have been popularised to the point that, today, it is difficult to decipher which of the quotes in social media artworks and in coffee table books actually originated from Rumi’s pen and heart, and which are mere ambitious and fictitious attributions to him. However, when Coleman Barks, one of the most famous Western interpreters of Rumi, says that a couplet is Rumi’s, it probably is.

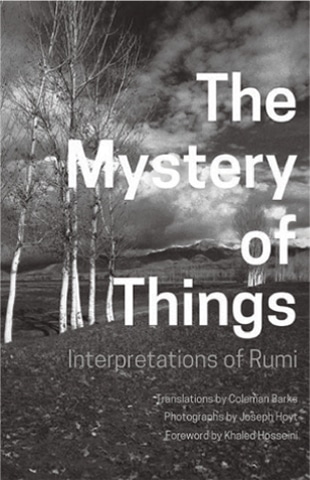

The works of Barks, complimenting some of the choicest images taken by photographer Joseph Hoyt, constitute The Mystery of Things: Interpretations of Rumi. Hardbound, visually delightful, and an easy and satisfying skim-through on a day when one is looking for nuggets of spiritual wisdom to answer deeper existential questions, the book touches just the right chords with today’s lover of Rumi’s works.

Hoyt’s earlier book, Afghanistan 1970-1975: Images from an Era of Peace, published in 2008, was when his photographs — based on the time he spent in Afghanistan — transitioned from being in exhibitions to taking form as a book. The Mystery of Things also started from being photographs on exhibit and are complemented by Barks’s writings based on Rumi’s verses.

Khalid Hosseini, author of the famed The Kite Runner, and Hoyt have had a long connection. Half of the proceeds from Hoyt’s first book went toward supporting The Khaled Hosseini Foundation to help with providing humanitarian assistance to communities in Afghanistan that needed it. It is thus befitting that the foreword of this book is written by Hosseini. In the foreword, he explains why photographs taken in Afghanistan are a suitable backdrop for Rumi’s verses: “Rumi’s soul was in the Afghan wind. It was in the air, in the water. You could hear it in the blind crooner’s song at a crowded street corner, in the extra beat he held the sorrowful notes, in the elegiac tremble of his voice. Rumi was everywhere. It is hardly surprising. Afghanistan is, after all, the birthplace of the great poet.” Hosseini goes on to call this book the perfect marriage between words and images.

The 44 images from Afghanistan in this book are simultaneously timeless in their human quality and nostalgic in the fact that they were captured by Hoyt’s lens in the 1970s, and thus remind one of an Afghanistan that has changed and evolved in many ways, owing to the many storms the country and the nation has weathered.

Perhaps that is something Rumi’s poetry also highlights in the human race. There is so much that is intransient in humans, owing to their inherent connection with the Divine. Yet the identity of humans keeps evolving. In this, there is much that is lasting and much that is fleeting and ever changing in humanity.

The selections of poetry are careful, and stirring, which is a quality archetypical to Rumi’s poems. Such as this quatrain:

Burning with longing fire

Wanting to sleep with my head on your doorsill

My living is composed only of this trying

To be in your presence

Another one, juxtaposed against a spectacular photograph of an amber-hued sunset — or sunrise — sky reflecting in still waters, is this classic piece of mystic poetry:

I keep asking, Who gives my soul

This increasing delight in what it does?

Who gave me life in the first place?

Sometimes I feel covered

Like a falcon mewed

Waiting inside its hood

Other times I can see

Then I get released into the sky

The art in the book is not limited to Hoyt’s photography. The sections are divided by selected verses from Rumi’s Persian poetry, calligraphed with a flow that is almost poetic, merging seamlessly into the philosophy that Maulana’s poetry offers. For this, calligraphers Ziaur Rehman Khan and Ali Alam deserve a special mention.

In Pakistan, the book has been published by the Bookgroup and the editors are Rakhshee Niazi and Sami Mustafa. The paper quality, layout and the touch and feel of the book, as well as the careful selection of the colour palette of black-and-white with greys, does justice to the content. It is a sensitively designed and printed book, with a gentle and aesthetic feel to it and not once does it overstep the boundaries of being in the periphery of Rumi’s mystic ideology. It is then safe to say that this is a layered book, in that it uses various media such as mystic poetry, calligraphy and impactful photography.

Yet another layer that may interest the Rumi aficionado is the fact that it is none other than Coleman Barks whose translations have been used as the main textual content of the book. To many, Barks’s work on Rumi has been the means to get introduced to the great sage’s poetry. To others, Barks’s work remains a debatable means for this introduction. For starters, Barks — according to some experts — is not known for his prowess of Persian, but rather as one who interprets existing translations of Rumi’s work, thus being the interpreter rather than the translator. But even if he is established as the translator as well as the interpreter, who is the target audience of Barks’s interpretations of Rumi’s work? The way Barks interprets Rumi’s poetry makes Rumi sound simply a mystic, and the image he paints of Rumi is what many have critically called a ‘non-Islamic Rumi’, whereas history has it clearly that Rumi — in addition to being a spiritual master and mystic poet — was a theologian, a scholar and a jurist of Islamic law as well. It is almost as if the mention of Rumi as a Muslim scholar has been erased from his works. Perhaps today’s human craves answers to the bigger questions in poems that are connecting him or her with the Divine as the Beloved, but does not wish to alter his or her lifestyle in accordance with Islamic jurisprudence. Thus, the Rumi described in Barks’s interpretation of him is one whose only creed is love. While this is very enticing to today’s audience, how close to reality it is remains debatable.

Nevertheless, Barks’s contribution to popularising and propagating the works of Rumi cannot be taken away. This book, thus, remains an important and refreshing addition to aesthetic printed renditions of the works of Rumi.

The reviewer is a Karachi-based journalist, editor and media trainer; human-centric feature stories and long form write-ups are her niche

The Mystery of Things:

Interpretations of Rumi

Translations by Coleman

Barks

Photography by Joseph Hoyt

Bookgroup, Karachi

ISBN: 978-9695503683

120pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, August 4th, 2019