Desi adaptations of Jane Austen’s work are usually hit-or-miss. That Regency-era England’s gender and class structures bear significant similarities to those of contemporary South Asian society is fairly obvious. But a good adaptation of Austen’s work would move beyond this generalised observation to offer the kind of witty and thoroughly nuanced social commentary that is Austen’s signature. Last year, an anthology called Austenistan was published in Pakistan, which was, frankly, atrocious. Partly because it didn’t engage in any meaningful way with Pakistani society’s intricate system of social class beyond the sliver of the uber-rich strata, or the way in which this system of class intersects with other axes such as caste and gender. Because of this, I went into reading Pakistani writer Soniah Kamal’s Unmarriageable, an adaptation of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, with not a small amount of trepidation. But I am happy to report that despite my scepticism, Kamal’s novel managed to charm me with the clever way in which it updates Austen’s plot and commentary to contemporary Pakistan while also being witty and enjoyable to read.

The major plot points of Unmarriageable can be neatly traced back to Pride and Prejudice: Alys Binat is the second-eldest daughter of the Binat clan, a family that came from landed wealth before the family’s head was cheated out of his inheritance by his brother. Cut off from the family business and the lavish ancestral home of the Binats in Lahore, Mr Binat, his wife and his five daughters have been living in the backwater town of Dilipabad. Here, 30-year-old Alys and her older sister Jena (the female characters’ ages have been appropriately upgraded for a contemporary Pakistani context, as the age when a woman becomes truly unmarriageable has fortunately shifted ever so slightly from Austen’s time) work as schoolteachers at a local branch of an English-medium school franchise. Their mother is eager to orchestrate advantageous marriages for her five daughters, but Alys is perfectly content in her singledom (or her growing unmarriageability, given her gender, age and class status), her ability to earn her own living teaching English literature and her illicit excursions to the graveyard behind her house to smoke with her best friend Sherry. Sherry has been updated from the 28-year-old Charlotte Lucas to a 40-year-old middle-class, single woman who has recently learned that she cannot have children, to underline the direness of her situation.

When the small town’s wealthiest couple throw a lavish, multiple-event wedding, the Binat clan is thrown into the orbit of the rich and charming Fahad “Bungles” Bingla, his two snobbish sisters and, of course, his taciturn, arrogant friend Valentine Darsee, all of whom are visiting from Lahore. The plot kicks off thereafter, with other notable characters making appearances, such as the pompous and annoyingly self-righteous widower Farhat Kaleen who tries his luck with Alys before eventually settling for Sherry, and Darsee’s estranged hunk of a cousin Jeorgeullah Wickhaam (I’ll admit, all the names made me chuckle) who, it turns out, has a penchant for seducing and impregnating unsuspecting young women — including maids — before absconding from their lives, and who (spoiler alert) eventually attempts to go off with Alys’s sister Lady to do the same without marrying her.

A contemporary Pakistani adaptation of Pride and Prejudice works because of its attention to detail when it comes to situating characters within a specific class context

The biggest strength of Unmarriageable is that the world in which Kamal situates the updated characters of Pride and Prejudice feels specific and realistically detailed instead of being vague and broadly sketched, and the characters themselves fully realised instead of empty homages to Austen’s originals. Alys, for example, is the right mixture of snarky, sensible and judgemental, and the novel even deepens Mrs Binat’s character (most adaptations tend to take the easy route of mocking Mrs Bennet). Her hysteria to marry off her daughters to wealthy men is treated less with ridicule and more with a wry empathy. Alys’s younger sisters — Mari, Qitty and Lady (real name Bathool) — are also fleshed-out characters who engage in the kind of banter and bickering that immediately feels lived in: in one of the funniest on-going jokes of the novel, the sisters take turns playfully accusing each other of making “you-you” eyes at the handsome boys in their orbit.

The Bennets’ world of Longbourne and Netherfield is transplanted to the small, fictional town of Dilipabad, which is a few hours’ journey away from bustling Lahore and which had been renamed after Dilip Kumar during a national craze to adopt home-grown names after colonial independence. This mixture of sly, tongue-in-cheek humour with a clear sense of the details of the novel’s world is also deployed when exploring the intricate ways in which wealth and lineage — or caste — intersect in determining each character’s position in the social hierarchy. This is reminiscent of Austen’s world, but feels, at the same time, very Pakistani. The Darsee family is described thus: “Although the Darsee clan had accumulated an immense fortune via the army, they did not come from noble stock. They were neither royalty, nor nawabs, nor even feudal landowners like the Binats. The Darsees descended, Mrs Binat announced, from darzees — tailors — and at some point their tradesman surname of Darzee had morphed into Darsee.” We also find out that Mrs Binat, before her marriage, was the daughter of a railways bookkeeper and herself worked in a beauty parlour and that the Binglas were the kind of highly educated but newly moneyed elite that divided their time between the United States and Pakistan.

There is, in Kamal’s novel, notable attention to detail when it comes to situating characters within a specific class context that Anglophone Pakistani fiction rarely manages to accomplish. Alys commutes everyday via the school’s vans, the Binat sisters get their clothes stitched from a trusted tailor instead of buying designer ready-to-wear lawn suits, and Alys’s secret indulgence of smoking doesn’t make the Binat sisters feel less awkward at the boozy, drug-laced parties the rich Binglas and Darsees frequent.

The novel also has interesting things to say about the way women in Pakistani society are allowed limited ways of being in the world, and how these options become even more limited the more time they spend being unmarried. Sherry’s decision to marry the much older widower Kaleen — who has children of his own and a hard-to-tolerate personality and who she does not love — in order to avoid the scorn of her brothers and of society at large, seems plausible when she outlines the things she stands to gain from the marriage: “Children. Hel-lo: S-E-X. Car, driver. And he’s a British citizen because of which I will become a British citizen. And then I will be able to sponsor my parents ... I’ve been working outside the home ever since I can remember, as well as inside cooking and cleaning, and I want to be in a relationship where duties will be shared.”

As Austen does in the original, Kamal juxtaposes Sherry’s views with Alys’s, both of whom are angered by the way in which their singledom restricts their lives, but who have very different views of how to live their lives in such circumstances. Alys is more outspoken in her perceptions and more unwilling to give in to what society dictates. “It is a truth universally acknowledged,” she says, “that hasty marriages are nightmares of bardasht karo, the gospel of tolerance and compromise, and that it’s always us females who are given this despicable advice. I despise it.” At times, her name-dropping of works of literature and her commentary on gender and post-colonialism become a little too pointed and overwrought but, given the fact that she is a literature teacher (who, let’s face it, can be slightly pretentious), it is not too difficult to let it slide.

All in all, Unmarrigeable works as an adaptation of Pride and Prejudice because it doesn’t let the romance overtake the social commentary, but also doesn’t allow the social commentary to be too sweeping and obvious. It walks the tightrope of reminding the reader of the best of Austen’s novels while also being an enjoyable narrative in its own right.

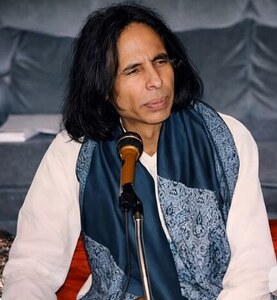

The reviewer teaches comparative literature at Habib University

Unmarriageable

By Soniah Kamal

Penguin Random House, India

ISBN: 978-1524799717

352pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, February 17th, 2019