EVERY educated Pakistani (and many an uneducated one) knows that a large part of the current crisis facing our nation can be put down to the much-harped-about-and-little-done-about problem of illiteracy. Pakistan’s literacy figures indicate that the government must act now on a war footing to boost school enrolments, and improve school facilities and the quality of education.

Is it any surprise that one of the strategies employed by the Taliban to destroy the fabric of society is to target schools? In a convoluted way, they understand (perhaps better than the elected government) that if you are to change society, you should target the education system.

In many ways, successive governments are more responsible for the current education emergency than any war-mongering extremist. But first, a look at the shining promises.

Article 25A of the Constitution states that all Pakistani citizens aged between five and 16 years have the right to free and compulsory education. In addition, Pakistan is a signatory to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 26 of the Declaration requires all signatory member states to provide free education to children.

And now, a look at the bleak education landscape and the stark challenges ahead. According to a report compiled by Alif Ailaan (an alliance that is campaigning to get more Pakistani children into schools), there are an estimated 25 million children in the country, aged between five and 16 years, who ought to be attending school but are not or, rather, cannot. Of these, 11.4 million are boys while 13.7 million are girls.

Actions do not match pledges to rescue education.

In another estimate, 57pc of all children who are out of school live in rural areas. And overall school enrolments at the primary level stand at a low 73pc.

In contrast, India and Bangladesh boast enrolment figures of 92pc at the primary level. These figures highlight the urgency and the massive level at which Pakistan needs to invest in education. Otherwise, we risk condemning a large percentage of our population to a life of unemployment and poverty.

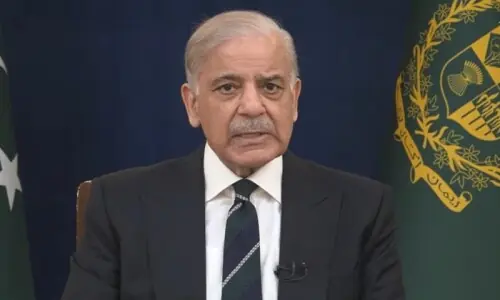

When it comes to explaining the yawning gap between the promise of education and the ground reality, it is no surprise that rhetoric abounds in an attempt to bridge the variance in the two. By now, jaded Pakistanis have really heard it all. This year in March, at an international conference in Islamabad titled ‘Unfinished Agenda in Education: the Way Forward’, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif said that for Pakistan, education is “not merely a matter of priority, it is the future of Pakistan, which lies in its educated youth”.

“It has, in fact, become a national emergency. More than half of the country’s population is below 25 years of age. With proper education and training, this huge reservoir of human capital can offer us an edge in the race for growth and prosperity in the age of globalisation. Without education, this resource can turn into a burden,” he added.

‘National emergency’, ‘human capital’, ‘edge’, ‘growth’, and ‘prosperity’, the prime minister used all the right words in his speech.

In practice, however, the actions lag far, far behind. Our government spends a measly 2.4pc of GDP on education. To add insult to injury, gimmicks such as using the precious little money reserved for education to hand out laptops (akin to doling out handouts to families of victims of terror attacks), only serve to divert focus from the real issue. The former hardly makes a dent in the literacy rate, just as handouts do nothing to prevent terrorism.

The writing on the wall is clear. An effective struggle (and it will take a struggle, no less) to increase literacy is going to be all about hard work: the hard work of building schools, the hard work of training teachers and the hard work of conceiving and undertaking effective campaigns to boost school enrolments.

We know that developing a skilled workforce is vital to sustaining a vibrant, strong and healthy economy. We also know that education is crucial if we are to achieve the dream of a healthy and tolerant society.

Yet all around us and every day, we see illiterate Pakistanis who face a lifetime of low wages and other issues related to living in poverty. They are at a greater risk for health problems, are vulnerable to exploitation and their children grapple with cognitive delays.

While there can be no one remedy that can deal with all the issues that ail this beleaguered nation, education comes close to being a panacea to our problems. For when we raise our voices and take steps to eradicate illiteracy from society, we are also raising our voices and eradicating related scourges such as poverty, hunger and disease.

The writer works for Public Interest Law Association of Pakistan (PILAP).

Published in Dawn December 14th , 2014