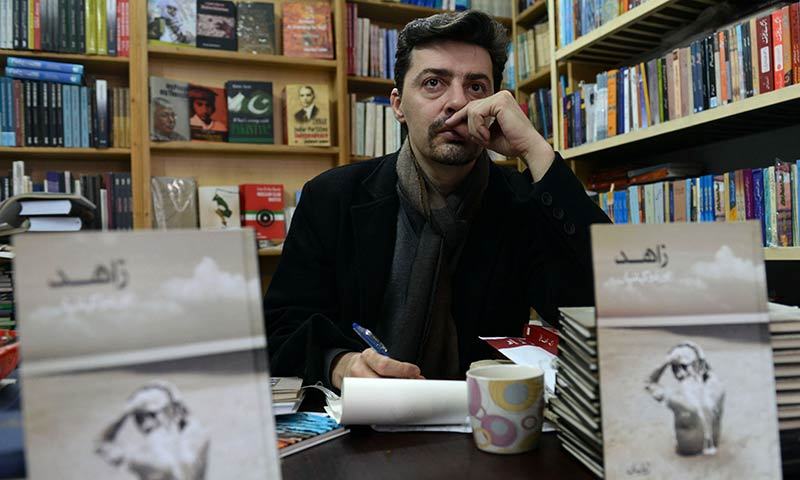

LAHORE: Frenchman Julien Columeau came to Pakistan at the age of 30 as a humanitarian worker - but a knack for languages and love for books have made him one of the country's most innovative Urdu novelists.

Writing mainly historical fiction with a prose described as vivid and forceful, critics say that Columeau, now 41, has injected fresh life into a scene considered to have grown stale.

His works have featured at the country's most prominent literature festivals with three novels published and more in the pipeline.

Originally from Marseilles, Columeau left France to study Hindi in India in 1993, but quickly grew disillusioned with the “clerical” form of the language he was being made to learn, and switched to Urdu two years later.

“I learnt it on my own - by then I was conversant in Hindi so there was a book which was about how to transliterate Urdu to Hindi,” he told AFP.

“Then I was practising my reading. After about one year I was able to read books,” he said.

He later moved to Pakistan with the International Committee of the Red Cross where he worked primarily as a translator in troubled areas.

Poets and martyrs

Columeau's first Urdu short story, Zalzala, or “earthquake”, came out after the catastrophic quake of 2005 and was set between a girls' school in Pakistani Kashmir and an apartment tower in Islamabad.

But it was when he turned his attention to Pakistan's iconic 20th century poets that Columeau's writing came into his own.

He became fascinated with 1950s poet Saghar Siddiqui, who fell into ruin and destitution and acquired a saint-like following among common people before his early death.

“I wanted to explore why he became a malang (a wandering mystic) despite the fact he was a successful poet and wrote songs for movies,” Columeau said of his first novel, “Saghar”.

“I used the gaps in his biography in order to construct my own fiction.”

After his death Siddiqui's legend grew and a shrine was built for him in the eastern city of Lahore, now mostly frequented by the working class and those looking for blessings and inspiration, including Columeau himself.

His second book on vagabond street poet Mira Jee was positively reviewed by 90-year-old Intizar Husain, widely seen as the greatest living Urdu writer, who is hailed for his works around partition and the 10-year dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq.

Husain told AFP Columeau's prose, which includes explicit sex scenes and details drug abuse, was a break from Urdu literature's usual euphemistic style. “His expression -- it goes beyond what we normally say,” said Husain.

Over the past decade or so, Pakistani English-language writers have become increasingly prominent and have helped expose their country on the world stage with works like Mohsin Hamid's “The Reluctant Fundamentalist”, which became a Hollywood film, and Mohammed Hanif's “A Case of Exploding Mangoes”.

Urdu is renowned for its beauty and poetry, but its literature has diminished in recent years and become primarily the domain of Pakistan's less visible lower-middle classes.

Novelty factor

In addition to pushing boundaries in terms of acceptable prose, Columeau has also been willing to tackle hot-button subjects such as sectarian violence between Sunni and Shia Muslims.

His third novel, “Martyr Munir Jaffry” concerns a firebrand Shia preacher whose father is killed by militants.

The book is written as a stream of consciousness with references to the Battle of Karbala, a seminal event in Shia history that many modern adherents view as a metaphor for present-day tragedies.

His latest collection of short stories meanwhile feature a cast of eclectic characters: a militant who later becomes a brutal pimp, an evangelical Islamic preacher from Kashmir who ends up lost in the jungles of the Amazon where he has gone to convert tribes, and a young Baluch insurgent who migrates to France after a series of tragedies.

It may sound difficult to pull off with authenticity, but Columeau proves himself up to the task, perhaps informed by his travels around the country for the ICRC meeting people from marginalised backgrounds.

“Nobody gets Pakistan's sub cultures like he does. Riveting,” Hanif, the English-language author tweeted about the collection in January.

His publisher and editor Amjad Saleem said that Columeau's status as an outsider looking in may be an advantage.

“There is a difference of civilisation, so Julian's observations about Pakistani society, his ways of understanding it and expressing it, are fascinating things for us,” he said.

Initially regarded as a novelty for being a foreigner writing in Urdu, Columeau says he used to feel patronised by some readers.

“That was an obstacle I had to overcome. The fact that people would not tell me about my book, its structure, its quality or defects, they would tell me about my language,” he said.

Now he says he hopes to turn stereotypes on their head.