On December 14, 2020, President Arif Alvi approved the Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Ordinance, 2020 and the Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020 to provide mechanisms for curbing sexual abuse crimes against women, transgender people and children.

Earlier, on November 7, the Cabinet Committee for Disposal of Legislative Cases approved these two ordinances to introduce harsher punishments for sex offenders, including chemical castration and the setting up of special courts to help expedite trials of rape cases.

The Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance 2020

This ordinance amends the Pakistan Penal Code, 1860 (the primary criminal law of the country) by modifying sections 375 on the definition of rape and 376 on its punishment. By expanding the definition of the offence of rape in Article 375, it widens the scope of rape and caters to as many categories as possible. The law is gender neutral, as ‘person’ means a male, female or transgender. It maintains the fact that consent from a girl below 16 years of age is irrelevant by making sex with a girl less than 16 years ‘statutory rape’. It also implies that minor marriage all over the country, including marriages of minor girls after conversion, are rape by law.

The law has introduced the new offence of gang-rape that was previously not an independent offence. By adding section 375-A, the offence of gang-rape has been added to the primary criminal law of the country, which has addressed a gap in Pakistan’s legal framework. The criminal liability of multiple offenders in gang-rape has been brought to parity and all offenders are to be punished under the principle of common intention, irrespective of the role played by each of them in the crime.

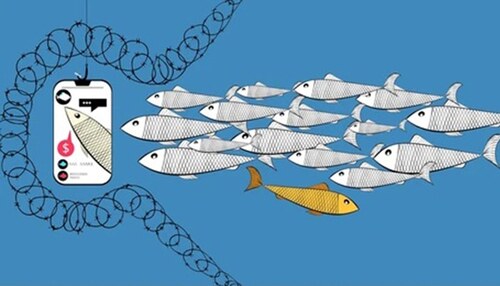

Is the new anti-rape law enough to protect society from heinous sex crimes that are on the rise? A human rights activist is sceptical about the harsh punishment it proposes for sex offenders

In addition, the new ordinance, by amending the second Schedule of Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898, has declared rape and gang rape as non-compoundable offences, where no compromise or settlement is allowed between the parties and a court must give the final decision The new law has also added section 376-B, which provides punishment of chemical castration for “exceptional first-time offender or repeat offenders” of rape and gang-rape cases. The law has removed the ambiguity regarding imprisonment for life by linking it to the “remainder of life” of an accused and clarifying that the offender has to be imprisoned till his natural death.

The Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Ordinance, 2020

Being an administrative and procedural law, this ordinance provides an administrative structure to the Anti-Rape Crisis Cells that are to be established by the prime minister throughout the country. Anti-rape crisis cells, headed by a commissioner or deputy commissioner, will be set up to ensure prompt registration of an FIR, medical examination and forensic analysis.

The law mandates medico-legal examinations of all victims within six hours of any sexual assault being reported. It can be enforced at both divisional as well as district levels and comprise commissioner/DC, district police officer, medical superintendent of the public hospital and an independent support adviser (ISA).

The concept of ISA is new in the country’s legal framework. An ISA has to be a lawyer, or a doctor, or a psychologist, or a social worker who has to accompany the victim to courts to prevent her/him from facing any duress or victimisation. The ISA has to be notified by the Ministry of Human Rights. At least, one member of the Anti-Rape Crisis Cell must be a female, according to the law.

Moreover, the Ministry of Law and Justice will appoint a special committee to take additional steps, including reaching out to any federal or provincial ministry, division, office, agency or authority, for the purposes of effectual compliance of this ordinance. The committee comprises individuals from any federal or provincial ministry, division, department, authority or office, or from members of the legal or medical profession, legislators, retired judges, serving or retired public servants, civil society or non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Under the ordinance, special courts will be set up nationwide to expedite the trials of rape cases on a priority basis. It calls for all cases to be resolved within four months. A fund to be set up by the prime minister will be used to establish the special courts designated under the ordinance. For this purpose, grants would be allocated by the federal and provincial governments, as well as international agencies, NGOs and individuals.

For first schedule offences (the law has two lists of sex crimes called First Schedule and Second Schedule), investigations will be carried out by police officers of grade BPS-17 or above, and preferably by a woman officer. The law has a provision to constitute Joint Investigation Teams for investigation of second schedule offences. Another point that relates to the police is that defective investigations have been criminalised through this law. Furthermore, if any police officer receives information about a scheduled offence or threat, they should immediately take necessary action to stop or prevent the commission of such offences, regardless of jurisdiction.

Nonetheless, to fill in the gaps related to statements through electronic means, legal provisions for an on-camera recording of testimonies of victims and witnesses have been provided. The protection of victim and witnesses in sex offences is the responsibility of the government. For this, rules are to be notified by the prime minister, but until the rules are so notified the protection can be extended through the Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act, 2017.

The ordinance also bars the cross-examination of a rape survivor by the accused. Only the judge and the lawyers of the accused lawyers will be able to cross-examine the survivor. To discourage the practice of denigrating the reputation of victims, evidence against ‘immoral character’ has been made inadmissible.

The law also abolishes the inhumane and degrading two-finger virginity testing for rape victims during medical examination and eliminates any attachment of probative value to it. The law also specifically prohibits disclosure of the identity of a victim of a sex offence and goes as far as criminalising the disclosure. On conclusion of the trial, the court may order the convict to pay compensation to the victim.

A significant feature of the ordinance is establishing a sex offenders’ registry at the national level, with the help of the National Database & Registration Authority (NADRA).

Critique

The two laws have been enacted without debate in parliament. The law also has empowered the prime minister to make the rules; this power was, in earlier legislations, vested with the federal government.

According to this legislation, the court can give the punishment of chemical castration to a sex offender, which is a process whereby a person is rendered incapable of performing sexual intercourse for any period of his life, as may be determined by the court, through administration of drugs.

No doubt, re-offending is a serious problem in sex crimes, but addressing it with such degrading punishment is arguably a matter of policy choice and may compromise Article 14 of the Constitution of Pakistan that protects the dignity of human beings even if they are offenders of the highest order. In addition, it brings the focus to retribution rather than on addressing the causes of the issues.

The alignment of this punishment with international obligations is also questionable. Article 7 of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Pakistan is a party, states: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. In particular, no one shall be subjected without his free consent to medical or scientific experimentation.” Pakistan has also ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in 2010, so the country is obliged to not bring any legislation against it, as it stands against the conception of dignity afforded to all people.

Some argue that this sort of punishment is commonplace, that Pakistan would not be the first to punish criminals this way. However, principally, this is a barbaric practice which would see Pakistan embrace vengeance and inhumanity rather than work to secure justice and improve conditions for vulnerable groups. Furthermore, in countries which have laws for chemical castration against sexual offenders, the process is intended to serve as rehabilitation for the offenders and is used as parole. The process requires a holistic procedure and is voluntary. It entails clear invasion of an individual’s person and cannot be done without consent.

Moreover, in countries where chemical castration is opted, systematic psychological counselling is also provided to the offenders. Otherwise, the offender can become more dangerous for the society after chemical castration.

Chemical castration was also proposed by a number of politicians in India after the Delhi gang rape case in 2012. The Justice Verma Committee constituted for law reform after the case, however, rejected it on the ground that chemical castration fails to treat the social foundations of rape, which is about power and sexually deviant behaviour. Sexual abuse is not just a crime of lust, it is a crime of dominance and violence and should be handled accordingly.

In 2015, when the Indonesian government added the procedure in its legislation, there was a massive protest from medical experts who refused to be part of it. They said that the act was a “violation to the country’s medical ethics.”

Nevertheless, the implementation of these two laws largely depends upon the police, which needs dire organisational and functional reforms. There is a severe gender imbalance to supply an adequate number of female police investigators. Furthermore, establishment of special courts is also a big challenge, as governments have not been able to establish juvenile courts in the past 20 years.

In addition, prosecution, forensics, and medico-legal services are being governed by the provincial governments. In order to effectively see the implementation, provincial governments have to take immediate policy and administrative measures. Training and capacity-building of all officials is a prerequisite.

The only way to stop rapes is to strengthen the criminal justice system: the police, medical, courts and jails. Instead of focusing on punishments, there is a need to work on creating sexual awareness and educating the community about rape.

The writer is a human rights activist. She works with Sanjog and is Executive Body Member of the Child Rights Movement.

She tweets @NabilaFBhati

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 10th, 2021