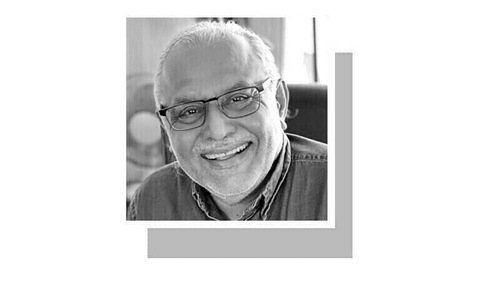

Veeru Kohli receiving the Fredrick Douglas Freedom Award in Los Angeles in 2009. — Photo courtesy Hasan Mansoor

HYDERABAD: Veeru Kohli was born to a landless Hari. From birth to now, her journey has been a tumultuous one – Veeru was married off to a family bonded to their landlord, managed to engineer a dramatic escape along with her relatives, and is now, astonishingly, running for provincial assembly seat PS-50 in Hyderabad.

On the top of her election agenda is to end bonded slavery everywhere – a cause close to her heart considering her past. Veeru lived in a small hut in the Hoosri neighbourhood of Hyderabad, along with her family of agricultural workers. Wearing a traditional ghaghra and an armful of bangles like every other Kohli woman, the 47-year-old has come a long way, she explains.

The activist, who now works tirelessly to get prisoners freed from private jails, was born to a landless Hari, a member of the scheduled Hindu caste, in Allahdino Shah village in the tiny town of Jhudo. At the age of 16, she was married into a family bound to a landlord because of a loan that was never settled.

Veeru was unable to understand why their loan continued to increase despite the fact that the family’s earnings were constantly adjusted with the landlord. Yet, she says, her ‘benefactor’ was far better than some others.

After 17 years, the family took a loan from relatives better off than themselves, and they moved on. They got a job with another landowner in Umerkot. The family had migrated with big dreams, but the man turned out to be a tyrant, and their dream turned into a nightmare.

This new landlord too had workers bonded by never-ending debts to work on the lands. They lived in tiny huts, surrounded constantly by armed guards. The guards were no less cruel, and would ogle the female workers, often openly threatening them or beating their husbands in front of them.

In the wake of this repression, Veeru decided to change things; she could no longer stand seeing brutalities around her. Seeing her son and daughter-in-law beaten on the day of their wedding, she helped the couple run away. Soon after, she overheard him ordering the guards to bring her to his place the next day. She knew she had no option but to flee the area with her infant daughter.

Veeru escaped, got onto a bus and found herself in a village safely distant from the landlord. There she had sent her son to her brothers. Her brothers and relatives helped her to collect money owed to the landlord to get the rest of the family freed but the landlord refused to free them, claiming the debt had doubly increased.

It did not let her down. She heard about the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) in Hyderabad and met its officials. They sent her to a senior police official in Umerkot to get her family freed. She was certainly aware of the threats that she could face – the landlord was influential and could have ended her life.

“Initially I was not fully prepared, but then I thought, this could be done only by me, so I went on all the way…”

Apart from eight of her family members, more than 40 other bonded peasants were imprisoned with the landlord. She went to the Umerkot police headquarters and refused to leave the place for three days, until a superintendent of police accompanied her to the virtual prison to get the labourers freed. The landlords’ guards thought it better not to resist when she came to them with a platoon of police force. Veeru’s unprecedented move came in the mid 1990s.

Following her feat, Veeru became the head of her family. It was time for her and her husband to start a new, free life. They changed location often, and finally decided to live in Hoosri, a small neighbourhood in Hyderabad district, just 15 kilometres from the city centre. Here she picks cotton and chilli in the field, while working simultaneously as a rights activist.

Unlike other Kohli women, Veeru has seen the world. She had seen most of Pakistan and been to India on peace missions. She has seen Delhi, Ajmer, Agra, Bikaner and other Indian cities. She visited Los Angeles in 2009 on receiving the Fredrick Douglas Freedom Award. She told to the audience there about some of her most horrific experiences: "The slaveholder hired men armed with guns and axes, and they guarded us the entire day," Veeru recalled. “They would fire their guns into the air at night to terrorise us so we wouldn't try to escape.”

“The slaveholder kept an eye on my daughters," Veeru said, adding that he had evil intentions with them.

Veeru’s husband died six years ago. She has 11 children – five daughters and six sons. Eight of them are married.

“Once I get elected, I will try my level best to get all bonded peasants freed. I have a dream to end slavery in Sindh for good,” she says.