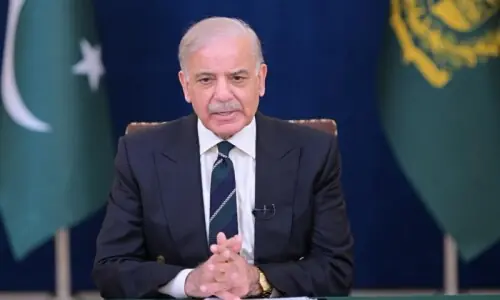

PRIME MINISTER Nawaz Sharif has perhaps done all that he could to draw the international community’s attention to the Kashmiri people’s ordeal. He and members of his large entourage spoke of India-held Kashmir to whoever they met in New York.

By all accounts offered by our media services, the Kashmir mission, carried out with unusual vigour, went off well — this despite a slight slip while drafting the press release on the meeting with US Secretary of State John Kerry and the attempt by Pakistan’s enemies to sabotage its efforts by attacking the Indian military camp at Uri.

But was the world listening?

The question is unavoidable in view of, among other things, the international community’s decision some years ago to delete the Kashmir issue from the list of its concerns. While voices may continue to be raised here and there in sympathy with the victims of oppression in any part of Jammu and Kashmir, the issue has been left to be resolved bilaterally by India and Pakistan. For many years now, the friends of India and Pakistan , and also of the people of Kashmir, have not gone beyond offering help to facilitate a negotiated settlement.

Pakistan’s establishment has traditionally held the view that large-scale disorder in the Kashmir valley, gross violations of human rights, or a popular uprising there will oblige the world community to intervene and help the Kashmiri people gain their rights. Despite being tested several times this thesis has not been confirmed. What will happen in future cannot be foretold, but political realism cautions against putting excessive reliance on the international community’s capacity to intervene effectively.

The whole of South Asia is paying heavily for the India-Pakistan confrontation.

Now that bilateral talks offer the only way to settle the Kashmir issue, Pakistan cannot but continue to give priority to efforts in that direction.

That India has responded with frenzied sabre-rattling, belatedly tempered with guile, is not surprising.

New Delhi justifies its horrible record in India-held Kashmir by arguing that it can make agitation in the valley prohibitively expensive. Further, it claims to possess the resources needed to absorb the cost of the Kashmiri operation. These arguments from the colonial rulers’ manual do little credit to India (or Pakistan, for that matter) after nearly 70 years of independence.

What India needs to ponder is the cost it is accepting for its policies in the long-term. It is asking its own people to sacrifice their rights to peace and prosperity for their state’s haughtiness or vanity. The whole of South Asia is paying heavily for the India-Pakistan confrontation. The hate campaign unleashed by irresponsible jingoists is threatening to destroy whatever is precious in the legacy of India’s sages and saints and in its forgotten creed of non-violence. Above all, India is ignoring the possibility that a genuinely reconciled Pakistan could support its bid to acquire its due place in the comity of nations instead of opposing it.

Notice must also be taken of India’s stock excuse for evading negotiations with Pakistan. Who, it is said in mock despair, should India talk to in Pakistan? The argument was irrelevant when Mr Nehru advanced it 50 years ago and it is irrelevant when it falls from Mr Modi’s mouth today.

What the sneer means is that, while in India the locus of authority is known and a relatively less privileged defence minister can sack a service chief, the government in Pakistan, even if it enjoys a large majority in parliament, is subject to the military’s veto.

This simplistic formulation may not always be valid, but assuming that it is a true reflection of Pakistan’s power structure, the inescapable conclusion is that India’s reliance on this argument in fact undermines an elected Pakistan government’s capacity to act for its people. It should not be difficult for the Indian politicians to realise that a democratic, non-theocratic Pakistan is the best neighbour they can ask for, just as a secular, democratic India is what Pakistan should wish to have by its side.

If Pakistan must do everything possible to find, through a peaceful and uninterrupted dialogue, solutions to its differences with India — because it needs its closest neighbour’s goodwill to a much greater extent than that of the ineffective religious groupings or self-centred big powers across the oceans — the argument is applicable to India too.

The writing on the wall is quite clear. Both India and Pakistan should scrape their conscience and ask themselves as to how long they want to see the flower of Kashmir cut down brutally in the street or entered into the list of enforced disappearances — and all this for the sake of their confrontation.

And should rethinking be limited to Kashmir?

The other day, four retired champions of the diplomatic processes pleaded, and rightly so, for reviewing Islamabad’s attitude towards Kabul and Washington. Perhaps the Pakistani people’s cup of misery needs to be filled up a little more to enable citizens of goodwill to call for a review of the policy of confrontation with India, which is becoming costlier and more meaningless by the day.

It is not necessary to enter into a controversy with Mr Modi over his threat to isolate Pakistan if we can stop isolating ourselves. What Islamabad should be worried about is the fact that international public opinion is increasingly losing confidence in Pakistan’s ability to manage its affairs. Why is the world bent upon painting Pakistan as a pariah? What is it that has made our foes more strident in their hostility than ever before and reduced our friends to offering superficial platitudes in our favour? The consequences of thoughtlessly wallowing in self-righteousness will be too grave to be entertained by any rational person.

Instead of waiting for the world to come to our rescue, we must resolve to pull ourselves out of the quagmire we have created by rearing the monster of bigotry and irrational violence within our polity. That is where the entire process of rethinking should start.

Published in Dawn September 29th, 2016