It is said that knowledge is power. It enlightens the masses and creates a consciousness among them to understand their environment and to improve their economic situation. In the past, in nearly all class-oriented societies, knowledge was monopolised by powerful groups such as the Brahmans in the subcontinent who did not allow the lower caste to become educated.

Education provided religious domination to the Brahmans. They conducted religious ceremonies and rituals and were appointed at high administrative posts. The privileged classes were not interested in educating the common people lest they become aware of their situation.

In early American history, slaves were not allowed to read and write by law. It was far easier to rule over the ignorant and illiterate rather than educated people. However, whenever political change disturbed the hierarchical system of society, the old aristocratic class made attempts to preserve its social status on the basis of family relations and claimed to have the same status that they had inherited from their ancestors.

In the 13th century India, the traditional society became distressed due to the introduction of new technology which brought about radical changes in the social life of craftsmen and artisans. As professionals, they acquired wealth and their social status improved. Some of them had access to education now and their intellectual talents came to light. As these changes challenged the old privileged classes, anger and disappointment grew in them against the lower classes who were now ready to challenge their established status.

Our flawed education system is deeply rooted in the history of the subcontinent

Zia-ud-Din Barani, author of Tarikh-i-Firoz Shahi and Fatawa-i-Jahandari represented the disapproval and resentment of the privileged class in his writings, in regard to the intelligent lower classes being appointed at high administrative positions on merit.

He argued that lower caste Muslims should only be educated in basic religious teachings that would make them good Muslims. They were not allowed access to higher education. In the works of Barani, higher education for common people was like putting pearl and diamond necklaces around the necks of swines and dogs.

His contempt for the lower classes was so intense that he could not tolerate their presence or company. He advised the rulers of his time to investigate the lineage of the person before appointing anyone.

Sadly, Barani’s views survive to this day. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, the great reformer and intellectual, who is regarded as one of the most important individuals to deliver the Muslim community from its decline, in fact represented the Muslim aristocracy and not the ordinary Muslim person. His interest was in educating and modernising the upper classes of Muslims who had lost their position after the fall of Mughal Empire. This trend is fully evident in one of his speeches delivered as chief guest in a madressah of Rai Breli. He was invited because he had become famous as a promoter of education among the Muslims of India. The headmaster of the madressah, addressing Sir Syed Ahmed Khan spoke proudly of the authorities being interested in not only teaching religious education to the students, but also to provide them with an opportunity to learn English.

In response to his speech, Sir Syed told the audience that he was shocked and disappointed to learn that English would be a part of the curriculum. He further said that the poor students whom he saw in the courtyard of the mosque studying religious text hardly required to be taught the English language. Accordingly to him, modern education was the right of Muslim aristocracy and not of common Muslims. To him, they should be given only basic religious education which would be enough for their livelihood. Moreover, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan was also against girls’ education. Therefore, his educational reforms were restricted to aristocrats and feudals.

The same policy continues in Pakistan even after independence. Missionary schools cater to the children of the elite classes; while there are expensive commercial schools where only elite people can afford to send their children and those who have more resources send their offspring abroad for higher education. These educated people occupy all the high government posts and rule the country.

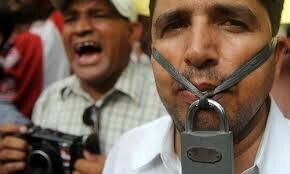

For the middle classes, there are educational institutions which train them to become clerks and subordinates to higher bureaucrats. For the boys of the poor classes the madressah is the only option where they can get basic religious education to perform different religious rituals and ceremonies. The rest of the people who have no access to any kind of education are available cheaply as domestic servants. The ruling and elite classes are not afraid of any challenge to their privileges and status because, for them, the system is perfect and should be kept intact.

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, July 27th, 2014