Modern cultural historians have usually defined the 1970s as being one of the most implosive decades of the 20th century.

Their fascination with the 1970s has continued to this day — they describe the era as a period in modern history in which various contemporary ideologies of the left and the right fought their most decisive battles.

The 1970s were no different in Pakistan as well.

Flamboyant and edgy, here too, the prominent veneer of freewheeling cultural brashness and populism of the decade finally mutated and triggered social profligacy and economic downturns that (by the late 1970s) eventually gave way (around the world) to the emergence of starker forces of the ‘New Right’. Who, in turn, would go on to redefine global politics and society from the 1980s onwards.

The cultural and political flamboyance of the 1970s eventually collapsed on itself.

Incidentally (and rather aptly), the 1970s in Pakistan were dominated by one of the country’s most enigmatic, flamboyant and contradictory politicians ever: ZA Bhutto.

On December 9 and 17 of 1970, Pakistan held its very first elections on the basis of adult franchise.

Political parties had been campaigning for the event ever since January 1970, and Z A Bhutto’s left-wing/populist Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), and Mujibur Rehman’s Bengali nationalist party, the Awami League (AL), were drawing the largest crowds in West and former East Pakistan respectively.

This did not seem to deter General Yahya Khan’s military regime. Yahya had been handed over power by the Ayub Khan dictatorship in 1969, after Ayub resigned due to pressure implied by a widespread students and workers movement.

Yahya did not trust either of the two parties (PPP and AL). But even though Yahya’s intelligence agencies had predicted a ‘slim victory’ for Mujib’s AL in East Pakistan, the same agencies had almost entirely rubbished the idea of Bhutto’s PPP ever sweeping the polls in West Pakistan.

Hopeful that the elections would at best generate a hung verdict (that would be in the interest of the military regime), Yahya, nevertheless, decided to not only support various conservative factions of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML), but it also gave a nod of approval to some right-wing religious parties that had been at odds with Ayub’s supposedly ‘secular’ regime.

During the PPP election campaign, new-found youthful, middle-class infatuations such as radical politics and revolutionary posturing connected with the street-smart vibes of the pro-Bhutto working-class milieu.

One of the most prominent connecting points in this context was Sindh and Punjab’s rural and semi-urban ‘shrine culture.’

The shrine culture, pertaining to the devotional, recreational, and economic activity around the shrines of Sufi saints, had been around in the region for over a thousand years.

Till about the late 1960s, urban middle-class Pakistan was either only nominally connected to this culture or many from the class had simply dismissed it as being the realm of the uneducated.

However, just like the hippies of the West (in the 1960s) — who had chosen various exotic and esoteric Eastern religions and spiritual beliefs to demonstrate their disapproval of the ‘soullessness’ of the Western capitalist system; and of the ‘exploitative ways of organised religion’ (mainly Christianity), young, middle-class rebels of urban Pakistan too, increasingly looked upon Sufism and the shrine culture as a way to make a social, cultural and political connect with the ‘downtrodden’ and the dispossessed.

Such a connect became more interesting when liberal and radical leftist youth supporting the PPP came into direct contact with the boisterous masses of rural peasants, small shop owners and the urban working classes at PPP’s election rallies.

The latter group brought with it the music, the emotionalism and the devotional sense of loyalty of the shrine culture.

The cultural synthesis emerging from such a fusion of ideas was a major reason behind Bhutto’s image graduating in leaps, and he was now perceived by his supporters as being the embodiment of a modern Sufi saint!

When the Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV) began showing clips of various election rallies, standing out in vibrancy and uniqueness were the PPP gatherings.

Though dominated by Bhutto’s animated populist oratory, these rallies also became famous for almost always turning into the kind of boisterous and musical fanfares witnessed outside the many shrines of Sufi saints across the country.

The country’s middle-class youth had blossomed in the mid-1960s as Pakistan’s reflection of the era’s youthful romance with leftist ideals.

But it was yet to be fully impacted by the ‘counterculture’ of the hippies making the rounds in the United States and Europe at the time.

That started to change in 1970 — and fast. Though the beginnings of the hippie phenomenon in the West can be placed in San Francisco in 1966, middle-class Pakistan’s knowledge of the phenomenon (till about early 1968) was at best superficial.

But when Pakistan became an intermediate destination of the famous ‘Hippie Trail’ — an overland route that thousands of traveling hippies (from Europe and the United States) started to take on their journeys towards India and Nepal — cities such as Peshawar, Swat, Rawalpindi, Lahore and Karachi in Pakistan became important hippie destinations.

After entering Iran (from Turkey), the Trail curved into Afghanistan, from where the hippies entered Pakistan (through the Khyber Pass in NWFP).

They traveled down to Rawalpindi and then to Lahore from where they entered India (by bus or train).

Many hippies also traveled all the way down to Karachi to visit the city’s sprawling beaches.

Popular destinations for these traveling hippies in Pakistan were the various large Sufi shrines in Lahore and Karachi.

About the same time, the middle-class Pakistani youth had also started to frequent shrines more often, especially on Thursday nights when numerous shrines held musical events dedicated to the traditional Sufi devotional music, the ‘Qawaali.’

It was at the shrines of Lahore; on the beaches of Karachi; and at the bus stands of Peshawar, where young Pakistanis came into direct contact with the passing hippies.

And as portrayed by the flashy (and flowery) attire of TV personality, Zia Mohiuddin, in 1970’s famous PTV ‘stage show’, The Zia Mohiuddin Show, the so-called ‘radical chic’ and ‘hippie attire’ developing in the West started to also catch the fancy of young urban Pakistanis.

By the early 1970s, young men’s hair, that had remained somewhat short till even the late 1960s, started to grow longer (along with the side-burns), and women’s kameez (shirts), became shorter.

Sure of triggering a political and cultural revolution in Pakistan, young West and East Pakistanis joined a large number of their countrymen as they turned out to vote in the country’s first ‘real elections’ in 1970.

These elections, though held under a military dictatorship, are still hailed by a majority of Pakistani political commentators as being the most free and fair ever held in the country.

The results were stunning.

Bhutto’s PPP (in West Pakistan) and Mujib’s Awami League (in East Pakistan), almost completely eclipsed the old guard of Pakistani politics.

Also swept aside by the populist tide of both the PPP and the Awami League were various religious parties.

In fact, the only religious party to perform well was the progressive faction of the Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI-H), which did well in the semi-rural and rural areas of NWFP and had originally wanted to get into a political alliance with the PPP.

The results of the elections were certainly a shock to the regime of Yahya Khan and the so-called ‘establishmentarian’ parties.

Winning around 160 seats in the National Assembly (out of a total 300), Mujib’s Awami League should have been invited to form Pakistan’s first ever popularly elected government. But since Mujib and his party were squarely made up of Bengali nationalists, Yahya hesitated.

Next in line to form the government was Bhutto’s PPP, which had won 81 seats.

What happened next is a thorny and controversial issue in the country’s political history.

Some political commentators have blamed Yahya for pitching Bhutto’s ego against that of Mujaib’s, while others accuse Bhutto of manipulating Yahya for keeping Mujib out in the cold.

Pakistanis have yet to decide upon a convincing closure on the issue.

Charged by the election results but frustrated by West Pakistan’s apparent reluctance to hand over power to the Bengali-dominated majority in the Parliament, militant Bengali nationalist groups started to violently agitate against the military regime of Yahya Khan.

As the drastic situation in East Pakistan rapidly turned into becoming a full-fledged Civil War, scores of refugees from East Pakistan crossed into the Indian state of West Bengal, drawing India into the conflict.

The turmoil soon mutated into an all-out war (in December 1971). But unlike the 1965 Pakistan-India war that had resulted in a stalemate, this time the Pakistani troops lost out.

Mujib was released from a West Pakistan jail to travel back to East Pakistan (via London), and take charge of the newly created Bangladesh and Bhutto took over the reins of what now simply became the Republic of Pakistan.

Bhutto reiterated his party’s commitment to introduce sweeping socialist reforms and give the country a proper constitution.

If one even skims through the economic stats of Pakistan between 1972 and 1974, the Bhutto regime (till then) did a rather remarkable job, considering that he had inherited an economy ravaged by an exhaustive war.

It is also true that during the first few years of the Bhutto regime, the nation’s mood had successfully transformed, as the country looked forward to a better Pakistan.

Of course, political skirmishes between Bhutto and the opposition parties continued making the news, but by and large, Pakistanis had decided to settle down and do whatever they could do to restore their pride after the East Pakistan debacle.

For example, on the youth front, university and college students, most of whom had been in an agitation mode ever since the late 1960s, returned to the campuses, willing and ready to conduct their politics through annual student union elections.

In fact, regarding campus politics, the Bhutto era (1972-76), is remembered to be one of the most stable, in which regular student union elections kept the students in a more democratic frame of mind.

More so, the political and social changes taking place in post-1971 Pakistan can clearly be gauged by observing the shifts and pulls witnessed in various universities and colleges in Pakistan during the Bhutto era.

For example, even though leftists were still a force on campuses, they lost the unity that they had exhibited in the late 1960s (during the anti-Ayub Movement). The country’s leading left-wing student outfit, the National Students Federation (NSF), broke into various factions.

By 1973, there were at least five NSF factions operating on Pakistan’s university and college campuses. Their influence was further diluted by the emergence of the PPP’s own student-wing, the Peoples Students Federation (PSF), and by the advent of various leftist-ethnic student groups such as the Baloch Students Organisation (BSO), and the Pashtun Students Federation (PkSF).

In response to the fragmentation of leftist groups, many progressive student leaders (in Karachi) formed the more moderate Liberal Students Organisation.

This fragmentation of the left on campuses was reflective of the (albeit quiet) sense of ambiguity growing within urban middle-class Pakistan.

The feeling seemed like a numbing hangover from years of playing a driven and confrontational political and cultural role in the late 1960s that had quite literally changed the map of the country (Ayub’s fall, the 1970 election, and ultimately the East Pakistan debacle).

Large sections of this class suddenly became apolitical, deciding to simply call themselves ‘liberal’ while the other half — especially in the wake of populist politics and Bhutto’s socialist reforms — tried to find a place for themselves in the changing political and cultural milieu by tentatively extending their support to politico-religious parties that had been swept aside by progressive and leftist forces during the anti-Ayub movement, and then during the 1970 election.

The latter tendency was also reflected in the time’s student politics. As progressive votes (during student union elections) started to split between various NSF factions, PSF and the liberals, the biggest beneficiary of the split was Jamat-i-Islami’s student-wing, the Islami Jamiat Taleba (IJT).

Remaining well organised and united, the IJT became a powerful electoral force on campuses in the 1970s — especially after 1973, when some of Bhutto’s economic policies and his confrontational style of politics started to alienate the country’s urban middle-classes.

In fact, as the opposition parties got bogged down by the PPP’s overwhelming majority in the Parliament and its burgeoning street power, the only worthwhile middle-class opposition faced by the Bhutto government came from the IJT.

However, there are still those among former student leaders of the left who claim that the IJT’s rise was actually encouraged by the Bhutto regime!

Bhutto faced desertions from what was once his natural constituency (the students), when between 1973 and 1974, he launched a purge in the PPP, expelling a number of the party’s leading leftist ideologues.

Leftist student groups (except the PSF) became opponents of the regime and some of the student leaders of the time suggest that to neutralise the opposition to his regime coming from far-left groups, Bhutto ‘allowed’ the rise of the IJT on campuses.

However, what such theories fail to take into account is that from the late 1960s, there was a two-fold growth in the number of students from conservative small towns and villages joining universities and colleges in the country’s main urban centres.

Such students became natural constituents of groups like the IJT.

Also, whereas the left groups had begun to split, the IJT remained united.

But the shift in the ideological mood of student politics did not in any way affect the populist cultural activity for which the Bhutto regime is fondly remembered.

The Pakistani society maintained a liberal aura.

Night-clubs, bars, horse racing, and cinemas continued to thrive and mushroom, and religiosity largely remained a private matter, even though the government and state of Pakistan started using religious symbolism more often than before — especially as a way to drown out an emerging post-1971 notion (among some sections) suggesting that Jinnah’s ‘Two Nation Theory’ that had given birth to Pakistan had collapsed after the separation of East Pakistan.

Pakistan’s tourism industry also witnessed an unprecedented boom during the Bhutto era, and the country’s Urdu film scene reached a commercial peak, a feat it would struggle to repeat in the future.

By now, flamboyant fashions that had been rapidly taking shape in the West — ‘bellbottoms,’ colorful shirts, long hair, heavy neck chains, platform shoes — arrived in full force and were enthusiastically embraced by urban middle-class youth.

Even though Western fashion and countercultural antics became all the rage among the urban young men and women, the youth’s desire to have a spiritual and cultural connect with the masses (discovered in the late 1960s) through the shrine culture too remained afoot.

Along with beer-serving roadside cafes in Karachi and Lahore, shrines too became a favorite haunt for students, and well known theatre artistes and painters.

For the Pakistan film industry, the culturally radiant times of the Bhutto regime produced a commercial bonanza as the industry managed to generate dozens of ‘super hits’ between 1970 and 1977.

To accommodate the large number of films being produced (mainly in Lahore), the number of cinemas also increased across the country, with the largest one (and the only cinema in Pakistan at the time to have a 70mm screen), appearing in 1976 in Karachi and appropriately called Prince Cinema.

A study of the Pakistani cinema of the 1970s in comparison to the Indian cinema of the period makes for an interesting case of contextual contrasts.

Both the industries at the time were generating films of similar production quality but (after 1973), when Indian Prime Minister Inidra Gandhi’s ‘heavy handed’ policies and the rising incidents of corruption in her government triggered a full-fledged protest movement (the ‘JP Movement’) against her, Indian films became more socio-political in context, throwing up Bollywood’s version of the ‘angry young man,’ epitomised by actor Amitabh Bachan’s brooding roles in various Salim-Javed scripted films.

Nothing of the sort happened in the Pakistani films of the time.

In comparison to India, which eventually went into a convulsive political turmoil when Indira declared a state of emergency in 1975, Pakistan’s economy remained comparatively stable and its politics were firmly in the hands of a Prime Minister who was hardly ever challenged by a disunited and fragmented opposition.

Even an armed insurgency by various nationalist Baloch groups in the mountains of the arid province of Balochistan (1973-77), remained somewhat in the background in the major cities of Pakistan.

So what were Pakistani films about during the 1970s — a time when the local film industry had hit a commercial and creative peak?

One of the major themes in the Pakistani cinema of the 1970s that managed to attract large urban middle-class audiences was class conflict explored within a romantic affair between a man and a woman; and the ‘Women’s Lib’ movement raging in the West at the time and its effects on the Pakistani society.

Thus, the Pakistani film heroines started appearing in roles reflecting a more independent and outspoken streak to the point of rebelling against their conservative parents by getting involved (and then marrying) middle or lower middle-class men.

1974’s ‘Samaj’ and 1977’s ‘Aaina’ are stark examples.

‘Samaj’ squarely blames the inflexibility of the conservative society at large for the quixotic rebellion of young couples going astray, and ‘Aaina’ offers a similar statement in which a trendy and rich young woman (played by Shabnam), falls in love with a lower-middle-class, albeit educated man (played by Nadeem), and after defying her disapproving father, marries the man.

The father eventually comes around to finally approving the union, but keeps offering gifts to her daughter (furniture, TV, air-conditioner, etc.)

This leaves the not-so-rich hero feeling as if his young wife’s father is mocking his lowly financial status. In between, the couple have a child (a son), but soon he is without a mother when the woman walks out, accusing the husband of being close-minded (if not downright paranoid).

Though, till now, the film is sympathetic to the whole idea of a modern young Pakistani woman using her own mind and will in social and domestic affairs, the sympathy turns into a question when we see her walking out on her man and that too without the son.

The question now was, whether such a display of independence (especially by women), may also end up making them behave selfishly?

After a lot of histrionics, in which we see the proud proud husband trying to raise the stranded child without a mother, and the mother gradually coming down from her contemporary pedestal of independence (thanks to maternal instincts now kicking in more often than before), the couple is finally reunited.

However, the film maintains its attack on social conservatism (especially the kind that stems from financial wealth), when it is revealed that the woman’s father had been trying to sabotage the marriage all along.

The revelation inspired the exhibition of an unprecedented scene never before dared in a Pakistani film. When the heroine realises how her father had destroyed her marriage and kept her away from her son, she lands a tight slap on the father’s chubby cheeks.

It was a daring statement by the director, Nazrul Islam. No South Asian film till that point had dared to incapacitate the sacred concept of fatherhood to such an extent.

The slap also expressed the modern, young Pakistani youth’s more aggressive retaliation against social conservatism, even though the heroin had to become a married woman and a young mother to be able to make such a drastic move.

‘Aaina’ was a massive hit. Opening in various cinemas in March 1977, the film ran for a staggering 400 weeks! It played for the last time at Karachi’s Scala Cinema in 1982 — a full four years after it was first released.

The other reason behind Aaina’s impressive performance at the box-office was its soundtrack. It was studded with catchy/moody songs composed by Robin Ghosh (Shabnam’s husband).

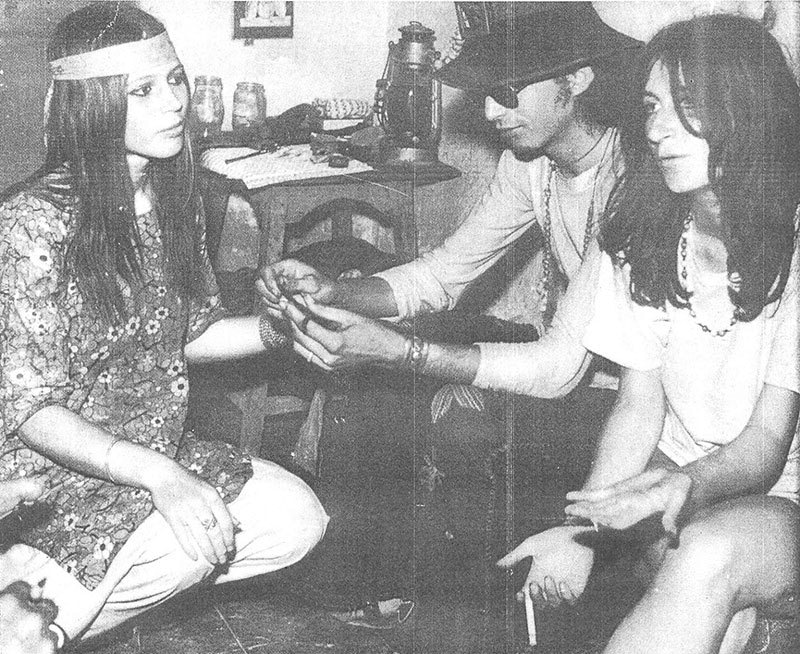

The first signs of the emergence of local hippies had started to appear in Pakistan in the early 1970s.

A report in a 1974 issue of The Herald suggested that the usage of hashish among young Pakistanis and college and university students had grown dramatically.

Interestingly, though, even till the late 1960s, hashish (among the middle-classes) was looked down upon as an intoxicant of the poor and the fakirs, by 1974 (according to the report), it had become increasingly popular on campuses.

But, whereas, (by 1974) in the West, the hippie and the counterculture movement had started to be ravaged by the rise in the use of deadly drugs such as heroin, in Pakistan, heroin was almost an unknown entity in the 1970s.

In fact, the first official case of heroin addiction in Pakistan was registered in 1979 (at Karachi’s Jinnah Hospital), many years after the drug had already become a serious problem within the youth cultures of the West.

The ‘swinging’ dynamics of 1970s’ romance with various social aspects of liberalism (in Pakistan) generated a rather crackling cultural aura when it came together with Bhutto’s populism.

However, at the same time, this fusion set in motion an anxious discourse (especially among the urban petty-bourgeoisie), who began to question the limits of the emerging liberal trends within the country’s middle-class youth.

This discourse too is clearly present in many of the time’s Pakistani films, most of which were scripted and directed by people with strong petty-bourgeois backgrounds.

The first shot in this context in Pakistani cinema was fired by 1974’s ‘Miss Hippie.’

The so-called ‘social revolution’ that the hippie counterculture eventually achieved in the West was largely seen as a cultural threat (by filmmakers) in both India and Pakistan.

The overall message of ‘Miss Hippie’ suggests that a patriarchal society is superior, and thus, when a patriarch fails, especially due to his liking for certain ‘decadent’ western abominations, the whole family/nation collapses.

That’s what happens to veteran actor Santosh in ‘Miss Hippie.’ He is a rich man with a taste for whisky and partying at nightclubs. He is thus a bad example for his impressionable young daughter (played by Shabnam) who too becomes a drunkard and a frequent ‘keelub’ (Urdu slang for nightclub) visitor.

Scolded by her hapless mother (played by Sabiha), Shabnam runs away from home, only to be picked up by a friendly ‘love guru.’ The guru is leading a group of hash-smoking and shake-shacking hippies.

Of course, this means an attack on the pure traditions of the ‘mashriqi mu’ashira’ (eastern culture); a threat that gets worse when we find out that the guru also runs a drug smuggling ring.

Enter Nadeem, playing an undercover cop who infiltrates the junkie-hippie group to report on how hippies plan to ‘contaminate innocent young Pakistanis’ with hashish and free sex.

Of course, true to form, the film passionately puts forth the breathtaking idea that it is the adoption of alien culture that is harming Pakistan, whereas ‘local culture’ (as interpreted by the urban petty-bourgeoisies), is its savior.

In the end, Nadeem destroys the sinister hippie group and rescues Shabnam from the clutches of drugs, decadence and assorted displays of nation-breaking obscenity.

‘Miss Hippie’ came with a funky soundtrack too, liberally laced with sonic allusions to the early 1970s’ ‘glam-rock’ (Garry Glitter, Marc Bolan, etc.).

The film also flaunted some of the most outrageous moments of the time’s ‘chic attire’ and overblown sense of fashion with Shabnam exhibiting a chunky metallic ‘Peace’ sign, platform boots, and bellbottoms with flares almost as wide as a Yosemite Park camping tent!

Taking the same route also was 1975’s mega-hit, ‘Muhabbat Zindagi Hai’. The film follows a modern young woman (actress Mumtaz) frequenting nightclubs and other such places of unparalleled wickedness, and having no respect for her own sacrosanct culture.

In comes actor Waheed Murad, playing an England-returned Pakistani who is also the fiancé of the independent-minded (and thus sleazy?) Mumtaz.

Waheed, however, is the epitome of eastern virtue and is shocked to see what has become of his old sweetheart. He decides to enter the ‘club life’ to have a shot at slowly making Mumtaz realise the follies of western culture. (Wonder what on earth he was doing in England?)

However, when he finally succeeds in making Mumtaz see the light, he himself falls prey to the manipulative ways of the club, as if it wasn’t a nightclub but a cult of brainwashed zombie alcoholics!

The reformed Mumtaz at once switches from wearing jeans to adorning shalwar-kameez, and from spouting free-for-all-English (“Eeeevverrrybaady, let’s enjeeayaayysss!”), she suddenly starts speaking in top-notch rhetorical Urdu.

The message of the film reeks of the convoluted formula upon which most of Pakistan’s ‘social films’ of the era were made in the 1970s; smugly suggesting that the Pakistani culture is sacred, whereas the western culture is like quicksand, sucking you in towards addictive immoralities such as booze, drugs, dance and rape! Of course, booze, drugs, dance and rape are all what westerners did all day long in the 1970s.

Though populist-liberalism was at its crest in the Pakistani society of the 1970s, films like ‘Ms. Hippie’ and ‘Mohabbat Zindagi Hai’ were portraying an undercurrent of anxiety boiling beneath the many liberal pretensions of urban society.

This anxiety (mostly affecting the middle and lower-middle-class sections), reflected a concern that saw society getting carried away by the liberal tides of the time and in the process, eroding the comforting economics and sociology of the ‘joint family system’ which, many feared, was gradually being replaced by ‘Western’ notions of social and domestic independence.

The liberal zeitgeist was also blamed (mainly by the more conservative sections of the urban middle-classes), for encouraging the youth to undermine the ‘importance of faith’ in the Pakistani society.

But such concerns and fears remained largely hidden underneath the bombastic antics of the populist-liberalism of much of Bhutto’s regime and era, and only surfaced onto the mainstream either through certain ‘social films’ — that, nonetheless, remained highly flamboyant in look — or through the concerned rhetoric of religious outfits.

However, the Bhutto regime’s take in this context too was rather ambiguous. Because in spite of the fact that the cultural policies of the government clearly encouraged and plumped the liberal aura of the period, some of the regime’s political maneuvers actually ended up strengthening the emerging anti-liberal narratives.

For example, after the 1971 breakup of Pakistan and the war with India, educational discourse of nation-building in Pakistan became much more introverted.

The shock and horror of the defeat in East Pakistan led to the refrigeration of the country’s ideological boundaries, making them narrower than before.

As author Rubina Saigol has noticed, a militaristic nationalism, which saw enemies on every border, was constituted.

This nationalism was not so much for progress or development as much as against Pakistan’s myriad enemies now presumed to be lurking behind every door.

Saigol goes on to explain that this new nationalism required a re-ordering of the past. Those unacceptable to the newly formed national self, had to be expunged. The pages of time had to be cleansed of the enemy’s presence.

Such narratives would eventually become integrated into larger state policies under Ziaul Haq in the 1980s, but one can also suggest that these early reactive maneuvers by the Bhutto regime — though also undertaken to neutralise the regime’s right-wing opponents — actually gave weight to the same opponents’ anti-liberal narratives which they would then, ironically, use in their first widespread movement against the regime in 1977.

The ambiguity of the regime in this context was also apparent on the state-owned PTV.

Though the 1970s are remembered as the ‘Golden Age of Television’ in Pakistan, in which the institution generated a series of high quality drama serials and music programming, many of the popular serials also addressed the same anxieties highlighted by certain ‘social films’ of the era.

Many of these serials either insinuated the Bhutto government’s populist-socialist overtones (Sonay Ki Chirya; Khuda Ki Basti); or were an apolitical celebration of various liberal notions of the time (‘Kiran Kehani’; Zair Zabar Pesh).

But there were also plays that indirectly addressed the dichotomy that emerged when the government-sponsored populist-liberalism clashed head-on with the new reactive historical narratives being built by the state after 1971.

The frontline player in this respect was intellectual and popular playwright, Ashfaq Ahmed.

A serial based on his teleplays called ‘Aik Mohabbat, Soh Afsanay’ (1975-76), celebrated the liberal signs of the times and the sense of freedom being exhibited by the middle-class youth; but the bottom-line of almost each and every play of his in the series was always a plea to balance modern notions of liberalism with the country’s traditional religious lineage.

Though on the surface the above may reflect a plea for moderation, the problem was, nobody was quite sure exactly what this traditional religious lineage constituted anymore.

Pakistan was (and is), a diverse population of various ethnicities, Islamic sects and sub-sects, so much so, that one’s ethnic roots start mattering more than the generalised concoction of a singular brand of faith — as proven by the Bengali nationalist movement in former East Pakistan.

Ashfaq’s balancing pleas emerged from his ‘Sufi’ bent, and since for a while he was a supporter of Bhutto’s socialist initiatives, Ashfaq had to rip into the ‘hypocrisies of the modern bourgeoisie’ before advising a balance between modern materialism and traditional spiritualism.

The above example is clearly visible in one of his most popular TV plays, ‘Dada Didada’ (1975), directed by Muhammad Nisar Hussain.

It is a story of a loving and liberal grandfather and his favorite young grandson who (with his long hair, charming personality and liberal ideas), is the stereotypical 1970s middle-class Pakistani youth.

The grandfather (Dada), also loves to drink (mostly whisky), and the family is happy radiating within the comfort of their liberal bourgeois cocoon, until the grandson falls seriously sick.

The vulnerability of the ‘liberal’ belief system is then ‘exposed’ when the doctors fail to cure the grandson and the family (especially the dotting grandfather) starts to crumble.

Ashfaq alludes that the glue that was keeping the family happy and together (liberalism and materialism), was of superficial quality because it had detached the family from its traditional spiritual moorings.

In a scene inspired by Mughal Emperor Babar’s sacrificial undertaking — in which, to save his son Humayun’s life, Babar is said to have given up alcohol — the grandfather prays to the Almighty that his life be given to the grandson and for this he is ready to give up drinking.

The grandfather then smashes all of his bottles and enters the grandson’s bedroom where the young man lies dying. There the old man starts to walk in circles around the young man’s bed until he stops and sits on the edge of the bed.

The next thing we see is the young man opening his eyes. He is cured. But in a tragic twist, when he approaches the grandfather, the old man is no more.

Ashfaq Ahmed’s TV plays of the era were a lot more literary and intellectual compared to the hyperbolic tenor of the time’s ‘social films;’ but the question is, was Ahmad also critiquing Bhutto’s populism, blaming it for encouraging the disengagement between Pakistani youth and faith?

The Bhutto regime saw Ashfaq as critiquing bourgeois-capitalist values, whereas Ashfaq was sure he was simply ordaining ‘Sufism’ in the ideologically vulnerable mindsets of modern young people.

The bulk of what emerged as art during the Bhutto regime remained celebratory, rejoicing it as soft expressions of the government’s populist overtones. But the dichotomy such a process was generating was unmistakable.

Perhaps it was the year 1975 in which one can place this process (and resultant dichotomy) reaching a peak; a year in which the success of ‘social films’ such as ‘Mohabbat Zindagi Hai’ (with its conservative undercurrent), was matched by the mammoth success of the notorious ‘Dulhan Aik Raat Ki’.

British and American ‘Adult films’ had become a hugely successful outing for young middle-class Pakistanis and couples, and by 1974-75, cinemas (especially in Karachi) that had signs saying ‘For Adults Only,’ were doing roaring business.

Karachi’s Rio Cinema and Palace Cinema became known for running such films. These films were mainly American romantic farces in which nudity scenes and voluptuous content were allowed to be shown by the censors, thus the tag: ‘For Adults Only’.

Inspired by the period’s ‘Adult Film’ phenomenon, director Mumtaz Ali Khan helmed Pakistan’s first Urdu film that was ‘For Adults Only.’

It was appropriately called ‘Dulhun Aik Raat Ki’ (Bride for one night). Staring the ‘Charles Bronson of Pakistani (and Pashtun) cinema,’ Badar Munir, the film was a raunchy meat fest of quivering female bodies and swinging muscular men.

The film was unapologetic in its gaudy, blood-splattered settings and amorality, spinning a story of unabashed hedonism, decadence and revenge, consequently giving birth to the prototype of the Pakistani cinema’s angry-young-man.

Badar Munir’s angry role was quite unlike that of Indian cinema’s angry-young-man of the time (Amitabh Bachan).

Where Amitabh’s role in this context was street-smart, brooding and ideologically charged, Munir’s role was that of a man steeped in the rugged and earthy myths of Social Darwinism, honour and revenge.

The character would eventually be perfected by Punjabi film actor, Sultan Rahi, in many Punjabi films of the 1980s, a majority of them based squarely on the formula first discovered by ‘Dulhan Aik Raat Ki.’

On the one end, the unabashed amorality of films such as ‘Dulhan Aik Raat Ki’ and, on the other end, the hit status of reactive ‘social films’ such as ‘Mohabbat Zindaggi Hai,’ clearly demonstrates the contrary nature of society and government in Pakistan under Bhutto.

Pakistan’s post-1971 liberal setting and energy had perhaps begun to exhaust itself.

There was a rise in ‘ghoondagardi’ (scoundrel behavior) in the streets and campuses of urban Pakistan, where flamboyantly dressed young men fought pitched battles with hockey sticks, chains, knuckle-dusters and bare fists, sometimes over ideology and sometimes over women.

Then, by 1976, the fruits of Bhutto’s socialist reforms (especially nationalisation), started to go soft, exposing the weakness in the ways of the regime’s reformist and populist economy.

But confident of being reelected as Prime Minister, Bhutto announced new parliamentary elections in early 1977.

Though by now aware of the urban middle-classes’ growing disenchantment with his regime, Bhutto was sure of his popularity among the urban working classes and the peasants and small farmers of rural Pakistan.

However, it was the urban middle-classes who had the most influence in the private print media and in student politics.

The once pro-Bhutto left (in urban Pakistan and on campuses) who had started to raise the tone of their grumbling against Bhutto’s ‘autocratic’ ways and his ‘betrayal of PPP’s original socialist agenda,’ and the conservative sections of the same class who had remained subdued during much of Bhutto’s regime, suddenly found themself gathered on the same platform.

This platform came in the shape of a 9-party political alliance between the country’s various politico-religious parties (led by Jamat-e-Islami), and some small anti-Bhutto secular groups (such as Asghar Khan’s Thereek-e-Istaqlal). The alliance was given a simple name: The Pakistan National Alliance (PNA).

Subsequently, PPP’s manifesto for the 1977 elections was a far cry from its manifesto for the 1970 elections.

To begin with, the word ‘Socialism’ now played only an obligatory role in the document.

Though still calling itself an ‘egalitarian’ and ‘poor-friendly’ party, the term faith now took up more space in the party’s manifesto and rhetoric than before. The political and social milieu of Pakistan had certainly started its gradual shift towards the right.

PNA’s manifesto however, not only attacked the ‘economic and political fall-outs of the regime’s socialist policies,’ its leaders vocally denounced the Bhutto regime for ‘spreading obscenity’ and ‘drunkenness’ among the youth.

The PNA aggressively stated its goal to replace Bhutto’s policies with those based on what it called, ‘Nizam-e-Mustapha’ (Sharia).

Thus, it was ironic that the PNA also included some overtly secular and leftist groups, though they were much smaller than the alliance’s religious outfits.

The bottom-line, however, was that the PNA was first and foremost a desperate alliance of various anti-Bhutto/anti-PPP parties and politicians who managed to capture the paradigm shift taking place in the ideological make-up of the urban middle-class and petty-bourgeoisie of the country.

The left-to-right shift is apparent in certain examples emerging in the country’s cultural milieu as it stood in late 1976.

The private print media started to run regular pieces by conservative columnists, and at times (especially the popular Urdu newspapers), published rumors (mostly about Bhutto’s supposed sexual and alcoholic escapades), as news items.

Certain Urdu magazines were suddenly ripe with exaggerated versions of ‘lecherous behavior’ driven by ‘immoral alcoholic frenzy’ that these magazines claimed were taking place in nightclubs, beaches and on campuses.

A paradigm shift in urban middle-class Pakistan’s ideological and political make-up was certainly afoot and economics had a lot to do with this shift.

Soon after 1974, the Bhutto era was replete with difficulties and challenges, particularly in terms of economy.

The period’s economic trends were hardly conducive for any third world economy to grow and prosper. A number of events that took place outside the control of the government were largely responsible for the poor performance of the economy after 1974.

Devastating floods in 1976 and an international recession between 1975 and 1977 due to the OPEC’s unprecedented hikes in oil prices severely depressed the demand for Pakistani exports, affecting industrial output.

Unlike the Ayub regime, the Bhutto government (and the state), did not play the role of sugar-daddy to the industrialists, and consequently, the gap between Bhutto’s economics of socialist reformism and the interests of the industrialists grew even wider.

By 1976, the industrialist and business classes started to pose themselves as being the economic muscle of Pakistan’s bourgeois and petty-bourgeois professional classes, so it was not surprising to see large and medium level traders, businessmen and industrialists putting all their weight behind the PNA.

The Bhutto government’s own ambiguity regarding its stand on socialism and its understanding of faith too contributed to the rhetorical attacks that he received from the PNA’s leadership.

For example, when in 1967, PPP ideologues, inspired by Nasser’s ‘Arab Socialism,’ had devised ‘Islamic Socialism’ as a ‘third way’ between Western capitalism and Soviet communism, Bhutto (in 1974) decided to demonstrate this on an international level.

He held an impressive International Islamic Conference in Lahore, where a number of heads of states of various Muslim countries were invited.

Though the speeches made at the well-attended conference described modern Muslim regimes and societies as being progressive, the tone of these speeches gradually became jingoistic while attacking Israel and the United States.

The conference also captured the imagination of the common Pakistanis who saw the proceedings on PTV.

The speeches made by Libyan head of state, Col. Qaddafi, and PLO leader, Yasser Arafat, received the biggest applause and were repeatedly aired by the state-owned channel.

The razzmatazz of the conference also saw PTV commemorate the event by producing several songs dedicated to the theme of ‘Muslim unity.’

One of the most popular songs in this respect was Mehdi Zaheer’s impassionate ‘Hum Mustaphavi.’

Though many of the ‘national songs’ aired by PTV and Radio Pakistan during the Bhutto era had socialist overtones and sang passionate praises of the country’s working classes, ‘Mustaphavi’ became the first Pakistani national song that used faith and Muslim as central catch phrases.

In Pakistan’s context, however — a country containing various distinct ethnicities, Muslim sects and sub-sects — this song was invoking a singular notion of Muslim nationhood.

Even while the Islamic Conference was taking place, and PTV was airing grand songs on Muslim unity, Pakistan was facing an insurgency in Balochistan by disgruntled Baloch, and had already witnessed vicious language riots between the Sindhis and the Urdu-speaking ‘Mohajirs’ (Muslim refugees from India) in Karachi (in 1972-73).

What’s more, the same year that the Islamic Conference took place (1974), the Bhutto regime decided to concede to the demands of the politico-religious parties and declared the Ahmadiyya community as non-Muslim.

In spite of the fact that the PPP clearly started to undermine its socialist credentials in its 1977 election manifesto, the party’s opponents in the PNA during their election rallies continued to attack Bhutto and its regime as being ’un-Islamic’ ‘oppressive’ and ‘obscene.’

In a number of rallies, PNA leaders asked their supporters not to vote for a Prime Minister who drinks alcohol.

In response, during a PPP election rally in Karachi (January 1977), Bhutto shouted to his listeners: ‘Yes, I drink. But I do not drink the people’s blood!’ (Haan mein peeta houn, laiken logoun ka khoon nahi peeta …!).

In this dramatic declaration, Bhutto was alluding to the industrialists who were said to be backing the PNA. But he couldn’t ignore the fact that PNA rallies were almost as big as those of the PPP, with the majority of the urban middle-classes now clearly supporting the PNA.

In March 1977, the people of Pakistan once again went to the polls (the first time after the historic 1970 elections). Initial results showed the PPP sweeping the National Assembly elections. However, the PNA leadership accused the regime of mass rigging.

Even though Bhutto agreed that there had been some incidents of rigging, the PNA boycotted the Provincial Elections, and announced a series of protests.

Just as left-wing student organisations had triggered the anti-Ayub movement in the late 1960s, the movement against Bhutto was set off by the right-wing student outfits, followed by their mother parties.

Most of the country’s campuses that had been bastions of leftist politics till about 1974, now erupted to the call of the right-wing groups.

PNA protests were mostly driven by students, small traders and shopkeepers. The bourgeois and the petty-bourgeois youth, who had overwhelmingly supported the PPP’s socialist maneuvers in the late 1960s and early 1970s, had now turned right, looking for the imposition ‘Nizam-e-Mustafa’.

The young protesters, upset by a recession and accompanying inflation, also attacked bars, nightclubs, wine shops and cinemas, denouncing them as symbols of the ‘depraved Bhutto regime.’

PNA leadership maintained that not only had the Bhutto regime’s socialism undermined Islamic culture and law, it had also failed to offer equality and relief to the poor.

The PNA leaders insisted that only ‘Nizam-e-Mustapha’ could guarantee justice and economic wellbeing to the poor — even though, ironically, the PNA alliance and movement was being financed by anti-Bhutto industrialists and, as some political commentators claimed, by the Jimmy Carter government in Washington.

Fearing a toppling and, more so, a military coup by the Army, Bhutto decided to hold talks with PNA leaders and if need be, hold fresh elections.

For this, he also agreed to close down nightclubs and bars and outlaw gambling at horse racing, and make Friday a weekly holiday instead of Sunday.

But just as a compromise between Bhutto and the PNA was in sight, Bhutto’s own hand-picked General, Ziaul Haq, toppled the regime in a military coup and imposed Martial Law on 5th July, 1977.

As they had done the late 1960s (against the Ayub regime), Pakistan’s urban classes had once again triggered a drastic change that was not necessarily constructive.

Even though this time, the country would not break-up, society as Pakistanis had known for many years, would, however, begin to change in the most unprecedented manner, even to the extent of its socio-political and cultural evolution facing a deep strain of socio-political retardation which it is still to recover from.

Resources:

• Syed, Anwar: The discourse & politics of Z A. Bhutto: Macmillan Books (1992)

• Khan, Muhammad Asghar: Islam, Politics & the State - The Pakistan Experience: Zed Books (1985)

• Ahsan, Atizaz: The Indus Saga: Oxford University Press (1997)

• Schimmel, Annemarie: Islam in India & Pakistan: BRILL Publishers (1982)

• Coleman, James William: The New Buddhism - The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition: Oxford University Press (2001)

• Miller, Timothy: The Hippies & American Values: University of Tennessee Press (1991)

• Paracha, Nadeem F.: Before the lights went out: Feature in DAWN Newspaper (July 10, 2008)

• Qureshi, Regula B.: Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali: Cambridge University Press (1987)

• Hall, Michael: Remembering the Hippie Trail: Island Publishers (1990)

• Khan, Lal: Pakistan’s Other Story - The 1968-69 Revolution: Struggle Publications (2008)

• Baxter, Craig: Pakistan Votes: University of California Press / JSTOR (1971)

• Burki, SJ.: Pakistan Under Bhutto: McMillan Press (1980)

• Bangladesh Documents Vol: 2: Ministry of External Affairs, India (1971)

• Kaiser Bengali interview by I H. Butt (2008)

• Student Union Elections Report at KU: HERALD (June, 1975)

• Farrukh, Nilofur: A Master Revisited: NEWSLINE (April 2004)

• The Pakistan Film Magazine

• Gazdar, Mushtaq: Pakistan Cinema - 1947-97: Oxford University Press (1997)

• Kazmi, Nikhat: Ire in the Soul: HarperCollins Publishers (1996)

• Khan, Adeel: Politics of Identity -Ethnic Nationalism and the State of Pakistan: Stage Publications (2005)

• Mughal, Owais: Pakistan’s greatest blockbuster

• Shakur, Anis: Voice of the Wind

• Pastner, Stephan: Baloch Fishermen in Pakistan: Asian Affairs, Vol:9, Issue: 2, (1978)

• Hashish Usage Rises on Campus: HERALD (June, 1974)

• Campbell, Richard S. & Freeman, Jeffrey B.: The Hippie Turns Junkie: Substence Use & Misuse Vol:9, Issue: 5 (1974)

• Clarke, Robert Connell: Hashish! - Red Eye Press (1998)

• Saigol, Dr. Rubina: Curriculum in India & Pakistan: South Asian Journal (October 2004)

• History of PTV

• Easterly, W.: The Political Economy of Growth Without Development: NYU (2001)

• Walpert, Stanley: Zulfi Bhutto of Pakistan: Oxford University Press (1993)

• Ahmed, Nesar & Sultan, Fareena: Popular Uprising in Pakistan: Middle East Reaserch & Information Project (1977)

• Richter, William L.: The Political Dynamics of Islamic Resurgence in Pakistan: University of California Press (1979)

• Zaidi, Akber S.: Issues in Pakistan’s Economy: Oxford University Press (1999)

• Manji, Irshad: Bhutto failed to Modernise Pakistan - CNN-Asia (2007)