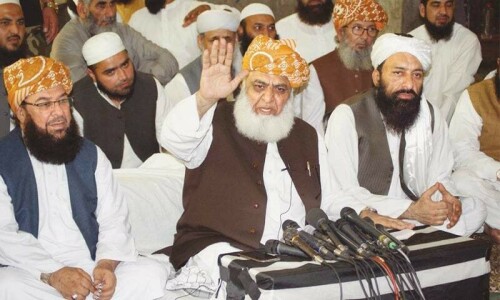

MAULANA Fazlur Rehman’s visit to Afghanistan was an ultimate attempt to repair the torn relationship with the Taliban. Pakistan hoped that maulana could help establish a direct communication channel with the Taliban’s supreme leader, Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada, who has remained secretive, like his predecessors, for enigmatic reasons. Whether maulana was successful in creating such a channel remains a mystery. However, Pakistan’s Foreign Office promptly distanced itself from his visit and his announcement about resuming talks with the banned Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

Maulana may have had several motives for visiting Afghanistan, both political and related to his personal security. The Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F) benefited significantly from the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, securing power in coalition provincial governments in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan while promising Taliban-style governance in those provinces. He may be expecting a similar outcome, hoping that a warm reception by the Taliban regime could further solidify his position in these two provinces. Additionally, maulana and other JUI-F leaders are under threat from the Islamic State Khorasan (IS-K) and the TTP. A satirical social media post by a prominent journalist aptly captures maulana’s potential ambitions, suggesting that a direct meeting with Akhundzada might deter the TTP from attacking him and his colleagues.

Maulana’s visit was surrounded by controversy from the outset. His followers in Pakistan portrayed it as an official Taliban invitation, but Taliban spokespersons denied this, stating that the visit was at his own request. Despite this, maulana attempted to appease the Taliban leadership by drawing questionable analogies between the situation in Gaza and the Taliban’s ban on girls’ education in Afghanistan. Informed sources claim that maulana might have carried a message from the Pakistani establishment, but the Taliban leadership remained largely inflexible in their stance regarding the TTP. They advised him that negotiations with the TTP were the only viable solution and should proceed without interference from Pakistani security agencies.

Pakistani journalists and religious scholars who recently returned from Afghanistan reported that the Taliban leaders are paranoid about the future of their regime, and their fingers are still hovering over the trigger. They suspect potential threats from their immediate neighbours, including Pakistan. This distrust might explain their reluctance to abandon terrorist outfits with transnational reach. The TTP, once a close ally during the Taliban resistance, has become a strategic tool in their hands, now directed against Pakistan.

Maulana’s visit to Afghanistan was surrounded by controversy from the outset.

Perhaps the Taliban aim to maintain controlled chaos along the Durand Line, keeping it volatile enough to deter the Pakistani military from blocking trade flows while still facilitating Pakistan’s access to Central Asia. However, this strategy is precarious. Such tactics are familiar to Pakistan and have countermeasures at the ready should tensions escalate.

The Taliban regime would know that conflicts rarely remain at a steady simmer. They know how quickly escalation can spiral out of control. The surprise Taliban offensive, launched while their team was still negotiating with the US, serves as a reminder of how quickly internal and external political-strategic landscapes can shift. Their initial misreading of the potential for internal resistance and the US’s response to their actions kept them at the doors of Kabul for a few days. Their entry into the capital without a fight was also a surprise for their fighters.

While some Taliban leaders accuse Pakistan of allegedly supporting IS-K, their reasoning can be attributed to a similar paranoid outlook. They conveniently overlook the fact that IS-K is just as ideologically driven as their own ranks and is actively instigating violence within Pakistan’s borders. With such a distrustful mindset, the Taliban are unlikely to offer Pakistan genuine assistance and will ultimately remain suspicious of every initiative it undertakes.

Pakistan is using all conventional channels to approach the Taliban and still believes that track two diplomacy through religious clergy can work a miracle. The belief is that if a direct communication channel with Mullah Hibatullah had been created, the state institutions would have convinced him to abandon the TTP and their vision of strategic connectivity with the region. However, Mullah Hibatullah and his close aides are very cautious and see Pakistan’s institutions through the similar lenses of common Afghans. Pakistani madressahs and clergy have come under the influence of the same perception.

Using religious scholars for diplomacy would not be helpful. Pakistani scholars may have a different take on some religious and political issues, but they believe in the Taliban narrative more than in the Pakistan state narrative. Though the Deobandi madressah and political leadership have not sworn formal allegiance to the Taliban head, in their sermons and writings, they refer to Mullah Hibatullah as ‘Ameerul Momineen’ (Leader of the faithful), and they do not waste any chance to defend Taliban policies.

Before maulana’s visit to Afghanistan, Pakistan had sent a delegation of well-respected religious scholars for confidence-building measures. They were also well-received by the Taliban, but they have yet to achieve any tangible results from their visit. Instead, the visit proved counterproductive as the Taliban and the TTP embraced them while using their religious decrees to justify their violent campaigns.

Any unsuccessful diplomatic venture through religious channels proves counterproductive as it creates a negative impression of the state and its institutions among the people inspired by the Taliban.

Maulana’s visit will likely face a similar fate and potentially increase Taliban influence within Pakistan. He might exploit the visit during his electoral campaigns, but his real test would begin if he succeeded in securing a government in Balochistan. Even a coalition government led by maulana’s representative would multiply challenges for Pakistan, including border security, visa-free movement at Chaman, the repatriation of Afghan refugees, trade, and the Taliban’s support for the TTP.

The Taliban would likely expect a similar response from maulana, which is precisely what Pakistan has been demanding from them.

The writer is a security analyst.

Published in Dawn, January 14th, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.