OVER the past four years, constitutional arrangements pertaining to centre-province relations in Pakistan have come under scrutiny from a growing number of quarters. Academic economists cite budgetary constraints placed by the NFC award on the federal government; the military high command, on several instances, has raised issues about the weakening of central state capacity and thus security capability; the current ruling party has called for an examination of how provincial resources are spent (citing corruption) and a rationalisation of fiscal devolution to shore up resources at the centre.

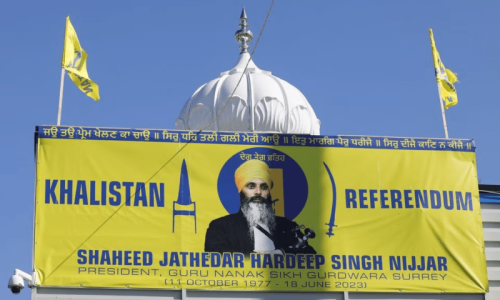

Anyone with even a cursory understanding of South Asian history would know that centre-region relations — shaped by ethnic differences — constitute a primary fault line around which politics is organised. This was true under the colonial government, when the opening up of representative spaces at the provincial level came into direct conflict with the retention of a bureaucratic and insular central government. The legacy was carried over into the post-colonial trajectory of India and Pakistan, where centre-province clashes over administrative, fiscal and cultural autonomy remain fairly frequent. Other than the secession of Bangladesh — the case that perhaps exemplifies this dynamic the most — other important cases of escalation in the region include Kashmir, Indian Punjab, Assam and Balochistan.

By passing the 18th Constitutional Amendment, Pakistan went some way towards addressing uncertainty in the country’s political blueprint. The 1973 Constitution was envisioned as a federal constitution yet it contained far too many aspects that undercut its own stated ethos. By removing many of those contradictions, and then eventually filling out the gaps created by the implementation of the 18th Amendment in issues such as environmental protection, drug regulation and taxation structures, some degree of coherence stands achieved.

The point here is not to mount yet another defence of the 18th Amendment as an unequivocal good (which others have done far more eloquently), but simply to point out that it was an outcome of political contestation and consensus. In other words, it was politics itself.

As a singular entity, the Pakistani state faces far fewer domestic pressures than in the past.

On that front, it proves itself to be a fairly successful intervention. As a singular entity, the Pakistani state faces far fewer domestic pressures than in the past. Active secessionist tendencies remain confined to the province of Balochistan, and even there — helped by demography and security interventions — the scale is far less than in the mid-2000s. All mainstream political parties practise centripetal politics. At least some of this can be traced down to the clarity that a coherent federal constitution provides. Domains are clearly demarcated and resource transfers are locked in. The basis for contestation therefore does not exist in the same way as it did in the past.

At the same time, though, to expect this state of affairs to continue unchallenged indefinitely would be to deny the nature of politics itself. Central state institutions, like the federal bureaucracy and the military, play a major part in the country’s politics and can be expected to resist interventions that limit their share of resources. The bureaucracy has been accommodated through the provision of lofty (upgraded) posts in the provinces, but the military cannot be shaped in the same way. This will continue to be a challenge in the years ahead.

Within the realm of democratic politics, challenges to the existing political settlement emerge not necessarily as a result of back-door conspiracy, but the changing nature of the polity itself. This, I contend, is based on the increasingly post-ethnic nature of politics in many parts of the country and one that advocates for provincial autonomy need to understand better.

The centre-province divide in Pakistan was one that, historically, mapped onto ethnic cleavages. First around the migrant and Punjabi elite versus the ethnic elites from other provinces, and then a central elite dominated by Punjabis (with some representation from smaller ethnic groups) versus excluded ethnic elites and their parties. The unrepresentative nature of politics for much of the late 20th century played a significant role in exacerbating these tensions.

As a result of this legacy, the 18th Amendment was also repeatedly highlighted as an ‘ethnic settlement’ — a federal arrangement that allowed for the cultural and political rights of particular groups that were spatially coeval with distinct provinces. Hence, even if the interventions it proposed were administrative and fiscal, the underlying logic was of identity-based rights.

Going forward, it is unclear whether that logic remains sufficient in a polity that is experiencing significant cultural transformation. In other terms, it is worth questioning if a defence of devolution on identity terms is sufficient in a country that has a large young and urbanising population which is increasingly (though by no means completely) consuming cultural content across provincial and ethnic lines.

It would be a folly to write off the future of ethnic politics, especially considering that it continues to shape identity-based claim-making in parts of Balochistan and ex-Fata; yet it would also be ignorant to claim that no change has taken place in how large swathes of the population associate with the Pakistani state. In particular, the success of the PTI in three distinct regions of the country — Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Karachi — signifies the ability of a non-ethnic party to incorporate different ethnic populations within its centre-facing politics. While not linear in any way, this is a trend that is likely to accelerate as populations become gradually even more integrated in national labour and media-consumption markets.

One consequence of these societal changes is that devolution will eventually have to be defended on the logic of its development and welfare potential, rather than solely on its ability to protect identity and cultural autonomy. And that shift in logic then, by its very nature, makes a case for devolving further down from the provincial tier to empowered local governments.

The writer teaches politics and sociology at Lums.

Twitter: @umairjav

Published in Dawn, August 10th, 2020