THE policy of keeping the rupee-dollar exchange rate fixed over extended periods of time, despite manifest signs of currency overvaluation, has not served Pakistan well. The parity was held around 60 during the Musharraf era, and around 100 in the recent Dar era. In both cases, unsustainable external deficits emerged, culminating in balance-of-payments crises requiring large shock devaluations and foreign bailouts to fix.

These intermittent currency crises are a major impediment to Pakistan’s long-term prosperity. They incentivise businesses to focus on short-term returns rather than long-term investments to boost the country’s economic potential. They deter foreign direct investors demanding macroeconomic stability and policy continuity as prerequisites. And, they weaken Pakistan’s geopolitical standing and sovereignty (bailouts are never a free lunch).

Yet, despite these nontrivial costs, we hardly see any ‘real-time’ opposition to this fixed rupee-dollar policy while it is in full implementation. One cannot recall any commentators (other than IFIs) clamouring for timely adjustment of the rupee during the Musharraf and Dar eras. And if this government decided to stabilise the exchange rate at 150 for the next three years, one expects few to object. Why? Because, unfortunately, the political economy is supportive of such a policy.

Pakistan’s opinion-makers are major beneficiaries of an artificially low rupee-dollar rate.

Pakistan’s opinion-makers are major beneficiaries of an artificially low rupee-dollar rate: it subsidises their spending on luxury imports (such as SUVs), children’s education abroad, and vacation travel. The masses don’t protest, as the more affordable import prices and lower inflation associated with an overvalued currency imply a quality of life improvement of sorts, albeit short-lived. Financing of the resulting higher imports/external deficits is also easier under a fixed parity as global banks generally lend in dollars.

One can ask why exporters do not protest the overvaluation policy. They probably do, but after years of import bias, the export lobby has weakened, and is overtaken in foreign exchange terms by overseas Pakistanis, whose remittances are largely insensitive to exchange rate movements.

The only way to break this unholy bias in favour of a low/fixed rupee-dollar parity is by raising awareness about its economic flaws and costs; and articulating an alternative currency regime to serve a volatile emerging market well. To this end, let’s examine why a fixed rupee-dollar parity makes little economic sense for Pakistan.

The correct measure of a country’s external competitiveness is its real, not nominal, exchange rate; the more appreciated the real exchange rate, the lower the country’s competitiveness, ceteris paribus. A percentage change in Pakistan’s real exchange rate equals the sum of: (i) the percentage change in the nominal exchange rate (where a more depreciated nominal exchange rate raises competitiveness); and (ii) the inflation rate differential between Pakistan and its trading partners (where a positive differential reduces competitiveness).

Assuming the US was Pakistan’s only trading partner, a stable rupee-dollar parity would guard against a loss in Pakistan’s competitiveness only if the inflation rates for Pakistan and the US are aligned. This is far from true: between mid-2013 (when the last IMF programme began) and end-2017, cumulative inflation amounted to 21 per cent in Pakistan vs 6pc in the US, implying a rupee overvaluation of 15pc vs the dollar alone.

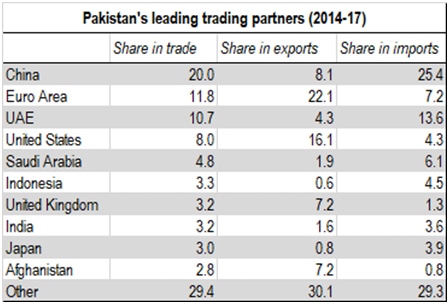

But Pakistan did trade not only with the US; 92pc of our recent trade was with other economies, led by China (20pc), the Euro Area (12pc), UAE (11pc). Unfortunately, inflation (21pc) was also higher than these other trading partners’ inflation (8pc), exacerbating the rupee’s overvaluation. Moreover, the currencies of these other trading partners depreciated on average by 9pc against a rising dollar, so with the rupee tied to the dollar, there was also a nominal rupee appreciation vis-à-vis these economies. The combined effect was a 22pc real effective (ie trade weighted) appreciation of the rupee between mid-2013 and end-2017. (A table and a chart, on Pakistan’s trade share with its major trading partners, and real effective exchange rate path, are included in Dawn’s web version of this article.)

The foregoing provides a measure of the massive external imbalance that had accumulated under the last government, and which had to be fixed. The rupee’s nominal depreciation in 2018 of 33pc should deliver a good part of the needed real depreciation, though probably not all of it. Pakistan’s non-US trading partners’ and other competitors’ currencies have also depreciated against the US dollar in 2018 (by 5pc and 18pc respectively, in median terms). Thus, the net improvement in Pakistan’s competitiveness due to the 2018 nominal devaluation of 33pc is likely to have been less than the around 22pc required to remove the overvaluation. (A table on the nominal currency depreciation of several of Pakistan’s competitors has been included in the web version of this article.)

If a stable rupee-dollar framework is not appropriate for Pakistan, what is? We can get a clue from Pakistan’s competitors. Most allowed their exchange rates vis-à-vis the US dollar to adjust early in the 2013-17 period (median depreciation was 13pc). This timely adjustment helped them avoid the cliff drop of 33pc the rupee suffered in 2018.

There’s no reason why a similar, more flexible exchange rate regime, anchored in a basket of trading partner currencies (rather than a single currency), should not work well. However, a more flexible regime will bring its own imperatives. With a more volatile currency, the private sector will need access to better instruments to hedge foreign exchange risk. The government would be well advised to develop futures and forward options that financial institutions and traders can access at reasonable cost.

Finally, a credibly independent State Bank, and clear communication are needed to regain the severely dented market confidence. If markets do not believe in the announced exchange rate policy, it is not worth the paper it is written on. Markets can bet (and win) against a currency even when the latter is in line with fundamentals. And the experience of the UK’s Black Wednesday (Sept 16, 1992) has shown that no sovereign, however powerful, can survive the market’s onslaught.

The writer teaches economics at SOAS, and is a senior research fellow at Bloomsbury Pakistan.

Twitter: @NadirCheema

Published in Dawn, January 14th, 2019