In this fourth installment of our ‘Crazy Diamonds’ series, we continue our tributary look at those promising Pakistanis who experienced the flip side of genius – an awkward and often torturous state of being that some describe as being a kind of madness. Previous Parts:

Crazy Diamonds – I Crazy Diamonds – II Crazy Diamonds – III

____________________________________

Waheed Murad

As if overnight, the industry started seeming like a pale reflection of its glamorous and lucrative past.

The VCR had arrived and with it Indian films (on video tapes). This machine boded well with what was happening to the film industry’s main audiences: i.e. the urban lower and middle classes.

Ziaul Haq’s reactionary military coup against the Z A. Bhutto regime in 1977 and then the military dictatorship’s strict censor policies, along with its concentrated crackdown on social activities that it deemed ‘un-Islamic’ and ‘immoral,’ began to push the urban middle-classes indoors.

The VCR fitted perfectly in this new, introverted setting. By 1984, Urdu films in Pakistan had already lost almost 50 per cent of its audiences. This was also the period when many cinemas began to close down or be converted into gaudy shopping plazas and wedding halls.

A number of once famous and rich film stars found themselves out of work. Some took to drinking and slipped into obscurity; some compromised their egos (and fee) and began doing teleplays; while others ventured into taking roles in loud, violent Punjabi films whose stock and popularity rose rather bizarrely with the strengthening of the Zia dictatorship.

This tragedy of the once untouchable and idealised film stars suddenly losing all their shine in Pakistan is most strikingly exemplified by the fate of a man who for more than a decade was perhaps the country’s leading film icon: Waheed Murad.

From the early 1960s till about 1977, it seemed that anything that Murad touched turned into gold.

His hairstyle after 1967 was repeatedly copied by young men and his lively romantic roles turned him into a heartthrob among millions of college girls and housewives.

Being highly educated also helped as he only accepted roles of ‘refined’ and gentle romantic men, who wore their hearts on their sleeves and demonstrated their optimistic disposition with an unabashed rejection of both irony and cynicism.

But when things in the industry began to experience multiple jolts after the 1977 military coup, Murad became the calamity’s first casualty.

He tried to reinvent himself as a character actor but the image of a jolly romantic attached to him was just too fresh and overwhelming for anyone to take his more grounded roles seriously.

Even though another contemporary of his, Nadeem, was still dishing out hits till 1979 (mainly due to his penchant of playing more realistic romantic roles), Murad began being ignored by the filmmakers.

The fall from where he was till 1977 was just too sudden and rapid.

Disoriented, baffled and bitter, the man whose car was once mobbed by dozens of collage girls and literally painted red with lipstick (in 1971), began to drink heavily and pop sedatives like they were candy.

When he appeared on a TV show in 1982 (Anwar Maqsood’s ‘Silver Jubilee’), Murad, by now skinny and with deep, dark circles underneath her eyes, sounded like a man on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

His wife of many years had temporarily left him when some film producers offered him to return as a hero but only if he would clean up his act. Murad agreed.

In 1982’s minor hit, ‘Aahat,’ he seemed to be playing himself. A broken man surrounded by empty whiskey bottles, medicines and the shattered pieces of what was once such a radiant life.

But destiny had marked him to fall even further. In early 1983, while driving under the influence of alcohol and sedatives, he smashed his car into a tree, giving his face a terrible scar.

After the accident, he tried to find solace in his two children and yet more (empty) promises by film producers.

They had to keep saying ‘yes’ to a man who had helped them make millions of rupees in the past. But, of course, they were in no mood to hire him again. Theirs was just a polite pitying gesture.

Frustrated and refusing to resign to his fate, in early 1984, the now 46-year-old former star, heartthrob and Midas, died of an overdose of sedatives. A film writer lamented that it wasn’t the pills and alcohol that killed Murad. It was a broken heart.

____________________________________

Atiq-ur-Rehman

Even the most passionate Pakistani cricket fans know very little or maybe nothing about a bowler who could have become the Waqar Younis or Shoaib Akhtar of the 1980s.

Those who are old enough to remember the 1983 Sri Lankan Under-19 team’s tour of Pakistan, may remember the sight of a young 17-year-old fast bowler from Karachi who was terrorising batsmen with sharp, fast and awkwardly rising deliveries even on the most placid of wickets.

Yet, Rehman failed to play in even a single Test or an ODI.

Arriving on the scene in 1982, by 1986 he was history (rather, a footnote).

Born in 1965 in Karachi, Rehman grew up playing cricket on the streets of Karachi and then on the cemented pitches of the city.

Australia’s Jeff Thomson (who, in 1975, had been recorded to have bowled deliveries that clocked up to 99 mph), became Rehman’s ideal.

Thomson’s record was finally broken by Pakistan’s Shoaib Akhtar in 2003 when one of his deliveries clocked at 100.2 mph!

At just 17, Rehman was knocking out some of Karachi’s finest club cricketers, but his rebellious and hotheaded temperament meant his advent into first-class cricket was halted by those who could have put his name up for Pakistan’s first-class teams to consider.

Nevertheless, in 1983, the then Pakistan cricket team’s manager, Intikhab Alam, while looking for bowlers who were good enough to bowl at the team’s front line batsmen in the nets, spotted Rehman playing a club game at Karachi’s Bakhtiari Youth Centre.

Impressed by Rehman’s pace, Intikhab asked him to report the next day at the National Stadium where the Pakistan team was practicing in the nets just before a Test series.

Rehman was one of the many young bowlers who were called up for the nets. However, when it came the turn for Pakistan’s two most talented and premier batsmen, Zaheer Abbas and Javed Miandad, to get some batting practice, Intikhab tossed the ball over to Rehman.

He bowled straight and fast to Miandad, who hopped around a bit, but negotiated Rehman’s pace pretty well.

He didn’t say anything and moved away to make room for Zaheer.

Zaheer too hopped around, but played Rehman’s straight, fast ones well until the young 17-year-old changed tact.

He delivered a vicious bouncer that rose and headed straight between Zaheer’s eyes. Zaheer jumped and just managed to block the ball from hitting his face with his left glove.

Shaken, Zaheer received another fast bouncer that almost knocked him off his feet.

Bruised and angry, Zaheer threw away his bat and began to hurl abuses at the young pace man. ‘Are you trying to kill me?’ he shouted.

But Rehman had had his moment. Right away he was picked to lead the pace attack for Pakistan U-19 team’s series against the Sri Lankan U-19s.

In that series he sent at least three young Lankan batsmen to the hospital, and it was during this series he caught the eye of Imran Khan who went on record to suggest: ‘This kid is bowling as fast as I am …’

Khan was out of the team at the time, suffering from a serious back injury. Zaheer had taken over the captaincy from him for Pakistan’s 1983 tour of India. Right away he insisted Rehman’s inclusion in the touring squad.

But Rehman could only get one game on the tour – a well-attended and televised day-night charity ODI against the Indian team.

After making a few Indian batmen hop and jump, Rehman got carried away and began bowling bouncers, most of them flying over the wicketkeeper’s head.

Warned by the umpires, he was taken off by the captain. Then, he got embroiled in some disciplinary issues with the team management and was sent back home.

In Pakistan he managed to get a contract from Habib Bank’s cricket team on the behest of the team’s captain, Javed Miandad.

When Imran returned as captain in late 1983 (though he was still struggling to bowl), he picked Rehman for Pakistan’s 1983-84 tour of Australia. Rehman bowled quick in some side games but broke down before the first Test.

He regained his fitness but his hotheadedness got the better of him. While visiting a club with some players in Melbourne, he got into a fight with some locals. He was immediately sent back home.

Imran suggested he start playing English County cricket to refine his talent, but the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) decided to coach him at home.

PCB’s top coach at the time, former fast bowler Khan Muhammad, was given the task of training and ‘disciplining’ Rehman. The first thing he did was to ask the young bowler to change his action. Bad idea.

Immediately Rehman lost much of his pace and bite. But the coach and Habib Bank insisted that he bowl with his new action.

By 1985 the young 20-year-old had fallen into a state of depression. Clearly losing pace and the fear factor with his new (enforced action) he tried to defy the PCB coach by reverting back to his action. But the sudden reversion wrecked his back.

In early 1986, after the end of the last day of a first-class game in Karachi, he disgustingly picked up his kit and left the ground never to come back.

He was just 21 when he decided to ‘retire’ and slip into oblivion.

____________________________________

Sikandar Sanam

Like these films, Sikandar too embraced a rather absurd and anarchic strain of the irreverence in which famous personalities and social issues were viciously parodied not just through spoofing, but by making perfectly normal looking characters deliver the most ridiculous dialogs with the straightest of faces.

Despite the immense popularity that his parody films generated, Sanam remained rooted in the social and cultural conditions from where he had first emerged.

He had surfaced from a vibrant tradition of stage comedy that mushroomed in Karachi in the late 1980s.

One Umar Sharif – a young, lower-middle-class resident of Karachi’s Lalukheth area (now Liaqatabad), and influenced by the spontaneous and witty ways of film comedians like Munawar Zarif (who died young in 1976) and Lehri – had risen to become one of the most street-smart comedians in the city.

When Sharif began doing stage plays, his scripts were entirely written in the kind of slang-ridden Urdu spoken on the streets of Karachi.

What’s more, it was his dialogues that the people came to listen to and laugh at and didn’t care much about the plot and acting.

That’s why from 1980 onwards, Sharif began creating cassette albums of comedy skits that sold in their millions.

Sharif’s audacity to bring on stage and tape the rough social wit found on the streets of Karachi began to impact and influence a number of other aspirants emerging from the same socio-economic background as Sharif’s.

They all came from lower-middle-class backgrounds and localities and were either Urdu-speaking (like Umar) or Gujarati speaking (Memon).

Each one of them reveled in using exactly the kind of lingo in their art that they did in their everyday lives.

Sikander Sanam was one such person. Sanam’s father was a struggling Gujjrati poet and the family lived in a congested locality of Karachi where Sanam went to school.

Sanam very early got involved with the street scene of such areas, where smoking, drinking, chewing paan and visiting gambling dens and brothels was a norm for young men.

Like Umar, Sanam too was a huge cinema fan and wanted to enter the industry as a comedian.

Already famous for his sharp wit among his school friends, in 1977, aged 15, Sanam found himself attending a stage play featuring Umar Sharif.

He was pleasantly shocked to see hundreds of people laughing away at Sharif’s jokes that were being delivered through a language and imagery that Sanam’s daily life was surrounded by.

That’s when he decided to become a stage actor. But his entry into the field was slow and unspectacular.

In the early 1980s he began to get bit roles in Sharif’s plays but he continued to study the master closely.

He noticed how Sharif (in everyday colloquial Urdu and Karachi’s street-speak), would brilliantly satirise, parody and mock everything from his own class background, to the ‘burger classes’ (the elite), the police and the mullahs, but then pad his mocking with a raving, rhetorical spiel on nationalism and patriotism.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s when the comedy theatre scene in Karachi hit a peak, Sanam had become an important part of Sharif’s team.

But Sanam was still just another Umar Sharif clone and sidekick.

He was also a good singer and tried to make a place for himself by releasing albums of parody songs.

It was in these albums that one began to notice Sanam trying to break away from Sharif’s influence and also getting rid of Sharif’s formula of padding his satire and parodies with rhetorical flourishes of patriotism.

Though the albums were not big sellers, they did bring Sanam close to a style of comedy that would finally turn him into a star; or someone not entirely attached to Sharif’s circle.

Influenced by Hollywood parodies like ‘Scary Movie,’ he began scripting, directing and acting in telefilms that spoofed famous Indian movies.

The idea was simple: Get actors to play characters from famous Bollywood blockbusters and then put them in the most typical social situations found in the congested areas of old Karachi.

It was like putting Salman Khan, Aamir Khan and Sanjay Dutt doing their glamorous Bollywood bit around paan stalls and rickshaw stands in Karachi.

Sanam always played the lead roles in these parodies, in which, undeterred by his paunch and skinny arms, he kept a straight face playing Salman Khan in ‘Bodyguard,’ Aamer Khan in ‘Gajni,’ et al.

The results were hilarious, and soon Sanam graduated from doing these ‘fims’ for local cable operators to doing bigger budgeted ones for the mainstream ARY TV.

Sanam had finally become a star in his own right. But just like Sharif, though loved by the ‘masses,’ he too continued to be rejected for being ‘crude’ by those more into the sophisticated comedy of men like the great Moin Akhtar and Anwar Maqsood.

It didn’t matter. Sanam had found his own style and recognition and he was now making more money than ever.

He had not only slipped from under his mentor’s nose, he had also bypassed the auto-erotic outbreak of so-called political parody shows on TV that have now become a mediocre nuisance if not an outright embarrassment!

But, alas, fate dealt him a cruel blow. Some of his ‘indulgences’ of the past took this vital and bright hour in his career to come back and haunt him.

In late 2012, when at the height of his popularity, Sanam was diagnosed with liver cancer.

Within days after the horrific diagnosis, Sikandar was dead. He was just 48 when he suddenly passed away and at the peak of his art, popularity and career.

It had taken him almost two decades to be where he wanted to be, but just two weeks to lose it all when death came calling.

____________________________________

General Rani

A muse and mistress of Pakistani dictator, General Yahya Khan, and many-a-times the main brain behind the swinging General’s regime, General Rani was the person a number of bureaucrats and politicians approached if they wanted Yahya’s attention.

Born in the Pakistani city of Gujrat into a well-to-do but conservative family, Aqleem was married off early to a policeman who was twice her age.

For years she played well the role of a good wife, bearing six children and never venturing out of the house without a burqa (veil/abaya).

Then one day in 1963, while holidaying with her husband on the cool hills of Murree, something snapped in her.

Walking with her husband among the tall pine trees of the hills, a gust of wind blew away the burqa from her face.

Enjoying the wind softly breezing across her face, she let the wind to continue making the burqa flap away and expose her face.

Agitated by her callousness, her husband admonished her. She stopped walking. She stared back at him and then casually proceeded to take off the burqa from the rest of her body.

Then after tossing it athim, she walked away, asking him to wear it himself!

She also took the couple’s six children with her but struggled to make ends meet when her parents insisted that they would only help her if she got back with her husband.

Alone, with six kids and without a job, Aqeel plotted to get close to powerful, rich men.

She began visiting those nightclubs in Karachi and other such clubs in Lahore and Rawalpindi that were frequented by the political, military and business elite.

Finding the men bored with their wives she began arranging ‘dance parties’ for them.

She used beautiful young women who had run away after facing poverty and harassment at home.

But instead of doing her ‘arranging’ business from the country’s two most famous red light districts (Karachi’s Napier Road and Lahore’s Heera Mandi), she operated from an apartment in Rawalpindi.

It was at a club that was frequented by the country’s top military men in Rawalpindi where Pakistan’s future dictator, General Yahya Khan, fell for her.

A compulsive drinker and womaniser, Yahya began an affair with Aqeel sometime in 1967. But throughout her relationship with Yahya, she kept insisting that they were ‘just friends.’

Nevertheless, when a leftist movement between 1968 and 1969 forced General Ayub Khan to resign as head of state, he installed Yahya Khan as the country’s new Martial Law Administrator.

It was at this point that Aqeel began being called (in the press), ‘General Rani.’ It is believed that apart from looking after Yahya’s ferocious appetite for booze and women, she also began ‘advising’ him on policy and political matters.

Those who met her in those days described her to be far more informed and astute in the field of politics than Yahya.

Soon she was being visited by all kinds of politicians, bureaucrats and military men, some asking her to arrange her now-famous dance parties for them, or get the General to meet them or do certain favors for them.

One of her clients was also Pakistan’s legendary singer and actress, Noor Jehan. She had approached Aqleem after the Income Tax Department had charged her for withholding thousands of rupees worth of income tax.

Noor Jehan asked Aqleem to request Yahya to intervene. Aqleem did. The General asked the income tax people to back off and then proceeded to begin an affair with Noor Jehan.

The daring woman who had rebelled against her husband’s conservative and demeaning behavior towards her, and then was left with nothing more than six hungry children and no consistent source of income, became a powerful, influential and rich woman during Yahya Khan’s short dictatorship.

The good fortune lasted till early 1972. Yahya, after leading Pakistan into a disastrous war against India and Bengali nationalists in former East Pakistan in December 1971, was disgraced when asked by the military and political parties to step down and then put under house arrest. He died in seclusion in 1980.

Z A. Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party that had won the majority of seats in West Pakistan in the 1970 election took over the reigns of power from the military.

Bhutto at once began to arrest military men, bureaucrats and politicians who had supported Ayub and Yahya’s dictatorships.

And even though it is believed that Bhutto was on good terms with Aqleem, he did not hold back and asked the police to put her under house arrest as well.

During the Bhutto regime (1972-77), Aqleem was constantly shuttled between house arrest and jail. Her cases were mostly challenged in the courts by famous lawyer, S M. Zafar.

She was finally released from house arrest when in July 1977 General Ziaul Haq toppled the Bhutto regime in a military coup.

But by then, she had lost most of her wealth and property and was back to being a pauper.

In the early 1980s someone advised her to get into a new kind of business that had begun to thrive during the reactionary Zia regime: drug smuggling and trafficking.

Though it is not known how much she got involved, but it is believed that after having a fall-out with some of Zia’s top military men, she was charged with drug trafficking and jailed.

She was bailed out by a few friends and the cases against her were quashed at the end of the Zia dictatorship in 1988.

Though, all her children had by now established themselves and become independent, Aqleem became a recluse, living alone and disallowed (by her children) to speak to the media or anyone who was not family.

She outlived most of her friends and foes, but it was largely a lonely, broken life. Suffering from cancer in the later days of her life, she quietly passed away in 2002 at the age of 70.

____________________________________

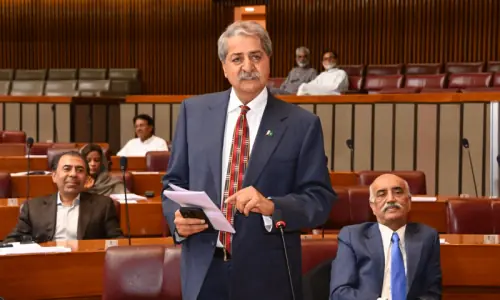

Meraj Muhammad Khan

The group’s attack was led by a fiery student leader called Meraj Muhammad Khan. The students were kicked, punched and arrested by the police and thrown in jail.

However, just four years later, the same student leader was sitting with Bhutto and a cluster of intellectuals, trade unionists, journalists and politicians all of whom became the founding members of Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).

Meraj was one of the most passionate student leaders to have emerged from the student politics of Pakistan in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Coming from an educated middle-class family based in Karachi, Meraj was a committed communist who joined the NSF in 1957 at college. He quickly rose to become an influential leader in the party.

He was also at the forefront of student agitation against the Ayub Khan dictatorship and was constantly arrested and jailed.

In the early 1960s due to the tension and hostilities between China and the Soviet Union, the NSF split into two factions, one pro-China (Maoist) and one pro-Soviet.

Meraj moved in to lead the student party’s pro-China faction along with his contemporary at the Karachi University, Rashid Ahmed Khan.

In 1965 when Pakistan went to war with India and the conflict ended in a stalemate, Bhutto accused Ayub of ‘losing the war on the negotiating table.’ He was chucked out from the cabinet by Ayub.

Of course, what Bhutto was saying was nonsense, but it did turn him into a hero of sorts for millions of Pakistanis who, during the war, had been told over and over again by the state media that Pakistan was devastating the Indian forces.

Bhutto became particularly popular among leftist student outfits that (in the 1960s) controlled the student unions and councils at most universities and colleges.

Mirroring the rise of leftist youth uprisings around the world in the mid and late 1960s, NSF’s pro-China factions fell behind Bhutto, urging him to lead a socialist revolution in Pakistan.

More a politician than a revolutionary, Bhutto instead decided to form a left-leaning social-democratic party and work towards replacing the Ayub dictatorship with multi-party democracy.

Energised by the support he got in West Pakistan for his stand against Ayub, Bhutto, along with Marxist ideologue, J A. Rahim, socialist theorists like Dr. Mubasher Hassan and Shiekh Ahmed Rashid, and ‘Islamic socialists,’ Hanif Rammay and Meraj Khalid, formed the PPP.

The party’s first convention was held in Lahore and attended by leftist and progressive intellectuals, trade unionists, journalists and politicians.

The most prominent student contingent at the convention was led by a 28-year-old Meraj Muhammad Khan who also joined the party.

Bhutto described the young Meraj to be a mirror image of himself and ‘my right hand man.’

When a widespread movement against the Ayub regime broke out in 1968, NSF factions were in the forefront, soon followed by labor and journalist unions and parties like the PPP and National Awami Party (NAP).

In East Pakistan, the movement was mostly led by the Bengali nationalists.

After Ayub was forced to resign in 1969, his replacement, General Yahya Khan, promised to hold free, multi-party elections.

During the campaigning, PPP rallies were disrupted by the members of the fundamentalist Jamat-i-Islami (JI) who had accused Bhutto and the PPP of being ‘atheistic’ and a ‘threat to Islam.’

It was Meraj and Sheikh Ahmed Rashid who, to fend off attacks by the JI, organised groups of NSF members to form the ‘Red Guards.’

The PPP won the majority of seats in West Pakistan. And when East Pakistan broke away to become Bangladesh, Yahya was forced out and Bhutto’s PPP took over the government.

At just 33, Meraj was made the Minister of Labor in Bhutto’s first cabinet. He was one of Bhutto’s most active ministers during the regime’s most left-leaning period (1972-74); and when the PPP’s leftist lobby was dominating the proceedings.

The movement against Ayub had radicalised leftist trade and student unions. The radical factor continued to grow after Bhutto came into power.

The PPP’s left-wing urged him to quicken the pace of socialist reform.

The slow pace of reforms forced trade and labor unions to begin a movement in Karachi (the most industrialised city of the country).

Factories were taken over and locked up by the unions leaving Bhutto fuming.

He saw the unions (most of whom had backed him in his fight against the Ayub dictatorship), as irresponsible.

‘How can you do this?’ He asked. ‘How can you lock up factories when we have just come out of a devastating war that has crippled our economy?’

He asked Meraj, who was close to the union leaders, to curb the agitation. Meraj refused and instead asked Bhutto to hasten industrial reforms.

Bhutto’s ego was notorious and he didn’t like the way his youngest minister was challenging his judgment.

In late 1973, Bhutto eventually ordered a severe crackdown against the trade and labor unions, and factories were forced open. Meraj resigned from the ministry.

Shortly after his resignation, Bhutto got Meraj picked up from his house by the police, beaten, and thrown in jail.

‘Bhutto’s right hand man,’ and the person who was destined to lead the PPP after Bhutto, spent the rest of the time during Bhutto’s regime in jails, and in and out of small communist parties. Suddenly he was a no-one.

Meraj sprang back to life when a movement against the Bhutto government began to take shape in early 1977.

Meraj was one of the many leftists alienated by Bhutto’s ‘betrayal of the socialist cause,’ who joined a movement that was primarily led by right-wing religious parties.

The movement created enough chaos for the military to justify its third take-over. In July 1977, the reactionary General Ziaul Haq toppled Bhutto and declared Martial Law.

Meraj after taking an active part in the movement again went into the background.

However, when the Zia regime got the courts to implicate Bhutto in a murder case and issue a death sentence against the former prime minister, Meraj now pushed to mend fences with the PPP.

Now leading his own small communist party, Meraj approached Bhutto’s widow, Begum Nusrat, to form an anti-Zia alliance of progressive-democratic parties.

But not before Nusrat demanded that he apologise for taking part in the movement against Bhutto.

Meraj was seen crying and distraught when he visited Nusrat Bhutto after Bhutto’s execution in 1979.

Nusrat finally agreed to form the alliance with seven parties (including Meraj’s). It was called the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD).

Bhutto’s daughter and future prime minister of Pakistan, Benazir, refused to work with men like Meraj, Maullana Mufti Mehmood (the father of Maulana Fazalur Rehman), and Asghar Khan, all of whom had taken part in the anti-Bhutto movement.

She is said to have barged into the alliance’s first meeting and screamed at her mother: ‘Mummy, how can you work with the people who murdered my father?’

But Benazir was made to apologise and accept the arrangement.

Meraj played an active role in all major MRD movements against Zia, and was jailed and tortured on a number of occasions.

It was as if he was trying to use the MRD as a cathartic exercise to exorcise the guilt of going against his former mentor and then watching him being hanged by a military tyrant.

After the Zia dictatorship folded when the General was assassinated by a bomb placed on his plane in August 1988, Benazir Bhutto was elected as the country’s new head of government.

It was expected that since Meraj had played an active role in the MRD, he would be taken back into the PPP fold.

But Meraj instead decided to reorganise the country’s communist parties, even though he insisted that his children stay away from politics.

Throughout the 1990s Meraj kept falling in and out of various small Marxist groups, until he realised that his political career was going no where.

In a surprising move he joined Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) in 1998 – a party that was rightist in orientation but populist in rhetoric.

Meraj, however, saw PTI and Imran as progressive. That is at least until 2003 when he stormed out of the PTI accusing Imran of being ‘dictatorial’ and a political novice.

By now in his late 50s, Meraj again went into the background. The man who could have had one of the brightest careers in politics almost vanished from the scene only to reappear briefly a few years later.

He could hardly speak and was suffering from severe health issues. Today, he lives a retired life, contemplating what could have been but wasn’t.

Many have blamed Meraj’s overtly emotional and impulsive disposition to be the main culprits behind him not realising the full potential of his political promise.

But there are also those who say that decades of activism for democracy and justice on his part should count for more than the many ministries he could have bagged in his almost 40-year career.

____________________________________

The views expressed by this blogger and in the following reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Dawn Media Group.