THE government must have heaved a sigh of relief on securing commitments from allies China, Saudi Arabia and the UAE to roll over Pakistan’s bilateral debt of $12bn for yet another year.

This rekindles hopes of approval of the new $7bn IMF bailout, crucial to shore up Pakistan’s official international reserves and meet its foreign financing needs, by the lender’s executive board later this month. These loans come up for a rollover at different times every year because we are unable to repay them due to a liquidity crunch. That these countries have apparently declined, or deferred, Pakistan’s request to extend the maturity period of the loans to three to five years to provide greater predictability over the tenure of the IMF programme shows that even friendly nations are hesitant to bet on us over the long term.

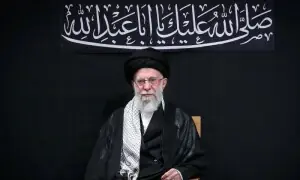

Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb, who broke the news on Tuesday, noted that our projected financial needs stood at around $3-5bn for the next three years, and that these funds could be managed comfortably. According to him, the government had received offers from foreign commercial banks for concessional loans and had hired a Chinese adviser to launch the Panda bond to initially raise $300m amid efforts to reprofile the Chinese energy debt of $15bn for a longer period to ease pressure on the fragile external account.

Indeed, Pakistan’s economy, which is characterised by a shrinking GDP, a balance-of-payments crisis and high inflation, has ‘stabilised’ in recent months thanks to the emergency loan of $3bn from the Fund. However, its short- to medium-term outlook remains uncertain. The country needs nearly $25bn annually to finance its large trade deficit and repay its foreign debt, while it has around $9bn in its reserves.

The new IMF programme is expected to help consolidate this newfound stability but the quest for faster and sustainable economic growth will remain elusive for years even if we move in the right direction. Most of us, including the policymakers, believe that compliance with the IMF’s tough conditions and its successful reviews constitute the much-needed structural reforms.

This, however, is misleading. Our deep-seated problems need tough and politically unpopular reforms beyond just securing a new bailout from the lender of last resort; the IMF loan will provide only temporary relief. The IMF is here to simply ensure that the country carries out its external financial commitments, because boosting economic growth or reforms in a client economy does not constitute the Fund’s mandate as such. Some 20 years ago, Pakistan’s economy was 18pc the size of India’s; now that figure is only 9pc. This is in spite of five bailouts from the IMF during that period. This means we must look beyond the temporary support of bailouts to overcome our crisis.

Published in Dawn, August 8th, 2024