THERE is no doubt that the first few years of this third decade of the 21st century have been filled by unexpected calamities across the continents. Covid-19 dealt such a blow to the world’s economy that even some wealthy countries faced recessionary conditions.

The less wealthy, naturally, were beset by even more troubled times when the pandemic knocked on their door. Many had to close down factories. Slowly, however, such countries are recovering, or at least have plans in place to strengthen their economy. In other words, they have acknowledged the truth that things cannot continue as they have been and some new approaches are required.

In Pakistan, in the aftermath of a contentious election — and even before — such plans and acknowledgement seem to be missing. The aftermath of the general elections has thrown the country into a greater miasma of uncertainty and fear, as a split verdict has emerged.

Last month, the State Bank confirmed receiving $700 million from the IMF — a part of the Fund’s ongoing Stand-by Arrangement of $3 billion. However, following the turmoil over the country’s political future and skyrocketing debt, the international credit rating agency Fitch has warned that uncertainty may hinder Pakistan’s efforts to conclude a deal with the Fund for securing further funding once the current bailout package expires next month.

While the agency acknowledged that the country’s external position had improved, with the central bank’s reserves going up from $2.9bn on Feb 3, 2023 to $8bn on Feb 9, 2024, it also warned that the increase was “low relative to projected external funding needs, which we expect will continue to exceed reserves for at least the next few years”. What was also of concern was its reference to “entrenched vested interests” in the country, which could resist another package entailing “tougher conditions”.

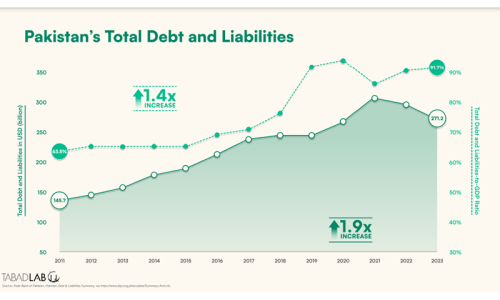

Apart from these international observations, in a well-researched report, the Islamabad-based think tank Tabadlab noted that the country’s unchecked spending and reliance on credit was simply unsustainable. The report noted that “Debt accumulation has been overwhelmingly used to continue fostering a consumption-focused, import-addicted economy, without investment in productive sectors or industry”.

One translation of this would be that successive governments have had a cavalier attitude and have done little to pull back on expenditures, allowing the same VIP culture of cars, lavish lifestyles, weddings, etc, to persist, thus creating a dumpster-fire that nobody is willing to put out for fear of seeing the ashes that will be left behind.

In the meantime, the country’s industrial sector which has fostered the growth of small-and medium-sized cities in Punjab in particular continues to suffer, battered by input costs, high interest rates, currency depreciation, energy sector woes and faulty trade policies. For the financial year 2022-2023, large-scale manufacturing shrunk by over 10 per cent in the country.

Pakistan’s poor credit performance means that its industrial sector has the region’s highest interest rate at a whopping 22pc compared to Malaysia at 3pc, India at 6.5pc and Bangladesh at 6pc. This comparison reveals that while all countries have faced the blows of similar global forces, including the pandemic, they are beginning to bounce back and are not at the dire level that Pakistan is.

The depressing prospect for the people of Pakistan is that there is no end in sight to their financial woes.

The second huge risk faced by Pakistan is related to the lethal impact of climate change. It is extremely likely that the continuing rapid rate of global warming will cause more catastrophic floods in Pakistan as glacial melt and climate conditions combine to create the certain storm. The consequences mean that agricultural production will also be severely affected, as is already being witnessed. Not only will climate change displace thousands, it will make the prospect of famine very real.

According to the report The Three Ps of Inequality: Power, People, and Policy, released by the UNDP a few years ago, approximately $17 billion were allocated for subsidies for the elite, which include the corporate sector, feudal elites and the political class. Elite privileges included tax breaks, cheap input prices, higher output prices, and preferential access to capital, land and services.

The report also found that the country’s richest 1pc own 9pc of the total income of the country and that the feudal classes who still do not pay taxes on agricultural income make up 1.1pc of the population and own 22pc of arable agricultural land. The military was mentioned as the “largest conglomerate of business entities” in the country.

The depressing prospect for the people of Pakistan is that there is no end in sight to their financial woes. No figures have emerged in the country’s history that show a plan for changing the system. And while that sort of revolutionary change is a tall order, the current concern is that even if a funding arrangement with the IMF is once again successfully concluded and the country does not default it will not end the misery of ordinary Pakistanis. If funding is approved, it will almost certainly bring more austerity measures, which have already contributed to inflation that is making it virtually impossible for millions of families to feed themselves.

There are solutions, but they will likely be ignored as they always have.

The Tabadlab report notes that “de-risking the business environment, adopting fiscal discipline and effective expenditure management, increasing foreign currency inflows for capital development through creation of special funds and partnerships to bring in capital for important projects, making internal recalibrations by management of state-owned entities and expansion of the public-private partnership ecosystem, expanding the direct tax net, establishing an export-oriented industrial policy and rethinking climate finance through leveraging debt-for-nature swaps” are all good strategies.

It is a pity that like before, like always, none of them will be adopted, pushing the country forward on a path of no return.

The writer is an attorney teaching constitutional law and political philosophy.

Published in Dawn, February 21st, 2024

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.