Most political pundits in the United States were left scratching their heads when results of this year’s midterm elections began to pour in. They had been projecting an outright rout of the ruling Democratic Party.

Rising inflation had badly impacted President Joe Biden’s approval ratings. Former president Donald Trump (a Republican) had predicted a Republican sweep. After Trump’s narrow defeat in the 2020 presidential election, the Republicans had been claiming that Trump was still the most popular politician in the country.

This claim was repeated over and over again by Republicans on TV news channels and on social media platforms. With Biden’s approval ratings falling and inflation rising, even anti-Trump analysts had begun to ‘accept’ the staying power of Trump’s popularity.

But contrary to what was expected, the Democrats performed rather well. Indeed, the Republicans won back Congress, but their majority in the new House of Representatives will be extremely thin. The results came as a pleasant surprise to Democratic Party supporters, most of whom were fearing a whitewash and a rout that would have made Biden a ‘lame duck president’.

As the results of the recent mid-term elections in the United States show, the perception of popularity often takes on more importance than actual popularity. But this perception is highly degradable

Republican-leaning commentators, who had played an important role in proliferating the perception of Trump’s popularity, suddenly turned their guns on him. They now think his ‘extremism’ dented the chance for Republicans to gain huge majorities in the Congress and the Senate.

Trump was allowed to handpick a number of Republican candidates. It was believed that Trump’s controversial views still held great traction and would pull in voters unhappy with inflation. Even anti-Trump analysts were taken in by these perceptions.

The apparently ‘unpopular’ Democrats focused their campaign on the claim of having taken difficult decisions to protect the country’s democratic institutions from being captured by ‘dangerous’ populists with rigid social/moral agendas and authoritarian tendencies. This perception was able to greatly neutralise the perceptions engineered by the Republicans, despite the fact that the latter had seemed to have more takers.

The results have been a setback for Trump’s ambition to run again as a presidential candidate and also for his ‘extremist’ narratives that many in the Republican Party tried to prolong, thinking they were still ‘popular’.

This seems to be a case of ‘Endogenous popularity’ (Buckley/ Marquardt/Ora John/ Tertytchnaya, V-Dem Institute, March 2022). Even though the mentioned authors were investigating perceptions of the ‘popularity’ of autocrats in non-democratic set-ups, their study just might explain how the perception of political popularity is woven in democracies as well. ‘Endogenous popularity’ is the perception of popularity that itself breeds popularity.

Favourable opinion polls or election victories can prevent voters from defecting from the perception of popularity that they build. Individuals may be more likely to express support for leaders if opinion polls and elections suggest that support for them is widespread. Contemporary authoritarian regimes try to shape citizen perceptions of the regime. Through their control of the media, electoral subversion and the suppression of opposition voices, dictators elevate their perception of popularity.

Yet, one can see similar tactics being employed by populist leaders and their parties in democratic countries as well.

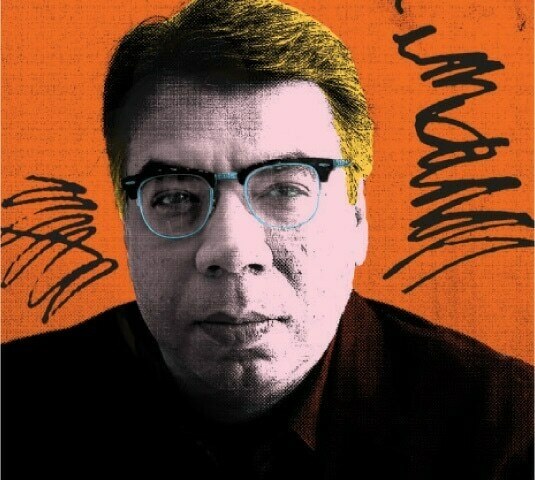

Even when they are in the opposition — as, for example, are Trump, certain far-right groups in Europe, and Imran Khan in Pakistan — they have ample opportunities to shape citizen perceptions through mainstream and social media. After being constitutionally ousted as prime minister in April 2022, Imran Khan attacked his opponents and former mentors (the military establishment) for working with the US government to engineer his ouster.

Khan’s approval ratings had plunged when he was ousted. But his accusations of having been unconstitutionally ousted at the behest of the US gained acceptance in many quarters when an alliance of anti-Khan parties formed the new government and was forced to take unpopular economic decisions to stall the country’s slide into possible bankruptcy.

Many commentators began to echo Khan’s claim that he had become the country’s most popular politician. Research in sociology shows that individuals susceptible to social pressure are willing to conform with the views held by their fellow citizens, even if this means that they have to discount personal beliefs.

The perception of Khan’s rebounding popularity — strengthened by a plethora of by-poll wins and his own oft-repeated claim of being a victim of a diabolical conspiracy who had risen from the ashes — drew in a lot of takers who didn’t want to be left behind in (even begrudgingly) appreciating his ‘resurgence’.

Yet, a closer exploration of the many by-polls that Khan’s party won after his ouster, can actually bring into question the perception of his resurgent popularity. Most of the seats that his party won were its own. And it also lost some of these.

Secondly, in another round of by-polls in which Khan contested on seven seats himself, he lost one. He only registered convincing wins in a handful of seats. Thirdly, the average turnout in the majority of the by-elections was extremely low.

This in no way substantiates the perception of resurgent popularity that he has built. It is endogenous popularity or a perception of popularity that is breeding popularity. But endogenous popularity is fragile, because it is based more on emotional appeal than on any tangible evidence that can withstand the test of time. In Khan’s case, this perception can only draw big votes if elections are held immediately. So the timing of the elections for him became extremely important.

Timing is equally important to the coalition government that replaced his fallen regime. In his book Election Timing, the political scientist Alastair Smith writes that “endogenous election timing allows leaders to schedule elections when the time is right.” In parliamentary democracies, this is the prerogative of incumbent governments. According to Smith, ruling parties often call early elections if they believe they will run into trouble in the immediate future.

But, according to the data provided by Smith, calling an early election during a peak in popularity doesn’t always transform into a big win. Instead, the decision “signals a leader’s lack of confidence in future outcomes.” This is an interesting conclusion by Smith which, if applied in Khan’s case, categorises him as a desperado who wants to quickly cash in on a highly degradable perception of popularity.

On the other hand, the besieged government is hoping that its insistence on hanging on to power and avoiding early elections will eventually begin to create a counter-perception of its confidence to pull the country out of its current political and economic crisis.

Published in Dawn, EOS, November 20th, 2022