ON Thursday, a little after sunset, there is something more to add to routine business and the customary congestion at Surjani Town’s Sector 8 as dozens of men, women and children are lined up outside a double-storey building along the main service lane waiting for their turn to enter the recently renovated structure while a few labourers offload cauldrons of cooked food from a charity service van.

People entering the building are asked to wear face mask and those who do not have it are offered one. This is Panahgah — first of its kind in the metropolis as part of Prime Minister Imran Khan’s initiative after more than 100 such centres have already been established in different parts of the country offering free food and shelter to the less privileged segment of society.

Surprisingly, the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf-led federal government has recently launched the project in the political territory of its rival Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) without the usual media fanfare and formal inauguration. Even more surprising is the fact that the Surjani Town Panahgah is not the only one in Karachi serving those without shelter, as the federal government has identified four more sites in different districts of the metropolis to set up such facilities.

Centre to run five Panahgahs in city

“The one is already functional [in Surjani Town] and sites have been identified for four more in Korangi, Lyari, New Karachi and Sohrab Goth,” says Naseem-ur-Rehman, the focal person for the government’s Panahngah programme.

The project with an aim to provide free food and shelter to the less privileged class of society from PM Khan started gathering pace last year after appointment of Mr Rehman who along with him brought experience of specialisation in development and humanitarian issues.

Having worked with global organisations and Imran Khan Foundation as its chief executive officer, Mr Rehman says it is just the beginning of the prime minister’s social development plan.

In a little more than a year, the project has set up 135 such facilities across the country and many of them are adding value to their services with the passage of time.

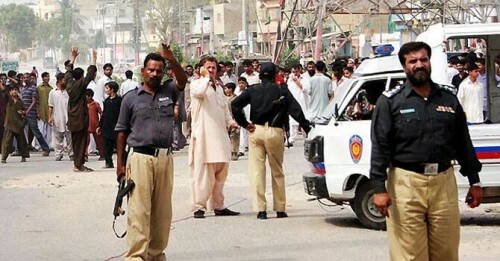

“This [Surjani Town Panahgah] is capable of providing food to some 500 people at a time,” says Ahmed Rind, an official of Pakistan Pakistan Bait-ul-Mal providing administrative support to the project, at the recently opened Panahgah while looking after the arrangements at the huge dining hall of the centre where the dinner is about to be served to the people sitting over multiple layers of chairs and tables.

With a portrait of PM Khan hanging over one of the walls, the first five rows are serving the men and the three rows behind them have been reserved for women. Just after a nod from Mr Rind, workers at the centre start serving. At each table, several dishes of rice, blended with beef, are served and refilled within no time.

“We also have arrangements for people seeking to stay overnight. Some 100 people can be accommodated here at a time, with separate beds for each individual, besides all the accessories needed in winter. The response is overwhelming as more and more people are turning up after hearing about the facility,” he says.

But how sustainable this initiative can be in a country where a change of government often results in ending the previous administration’s projects. It is hard to answer this in Pakistan but standing here at the dining hall one can witness the Surjani Town Panahgah as a timely relief for many.

Having dined for a third consecutive night, with her two daughters and a son, Hamida Bibi explains it well. For the housemaid from a rural Rahimyar Khan area, who migrated to Karachi some 11 years ago and lost her husband in a road accident in 2014, it’s a “simple math”. She says: “I have to spend at least Rs150 to Rs200 for one time meal for my family [of four]. Even if this [Panahgah] offers me a one-time meal I can save between Rs7,000 and Rs8,000 a month. This makes the salary of two homes where I work. It is more than enough for me. I only have prayers for the one who has taken this initiative.”

Asked about the money she would save from the state-sponsored initiative, Hamida Bibi does not take a second to respond: “I will get them schooling. What else?” she says, looking at her daughters and son sitting across the table.

Published in Dawn, February 8th, 2021

![A FAMILY — a father [left] and his two children — is among many who are offered meals at Surjani Town Panahgah everyday.—Fahim Siddiqi / White Star A FAMILY — a father [left] and his two children — is among many who are offered meals at Surjani Town Panahgah everyday.—Fahim Siddiqi / White Star](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2021/02/60206e3f5e592.jpg)