The Haunting of Bly Manor

I have a problem with the way children are imagined in horror movies and series. When not stoic — which is almost never these days — they’re unusually smart and immeasurably insufferable.

So, in The Haunting of Bly Manor, a reimagining of Henry James’ classic horror novella Turn of the Screw, when we first meet Flora Wingrave (Amelie Bea Smith) — a British child of barely 10 years whose sentences end with the words “absolutely splendid” — you’d want the ghost of the story to really scare the daylights out of her.

That is, you wish it until the first 15 minutes of the first episode.

Writer-director Mike Flanagan (Oculus, Ouija: Origin of Evil), who seems to have found his niche in long-form gothic-supernatural-drama storytelling, is most certainly a master of leisurely paced, layered stories. His craft was near-perfected in The Haunting of Hill House, and gets a fine coat of sheen in Bly Manor, which clocks in at nine episodes.

That’s one episode less than the last series. And a good thing it is. At its current length, the series is crisp and to-the-point.

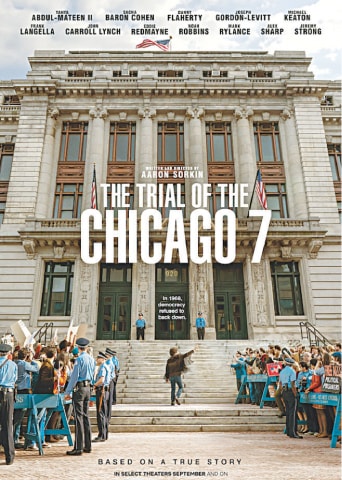

Two Netflix releases reviewed: The Haunting Of Bly Manor comes out as nothing short of brilliant; and Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7 highlights issues of war and peace, democracy and order, justice and racism in one fell sweep

While Flanagan doesn’t direct or write every story in the series (excluding him, there are six credited directors and eight screenwriters), with the way the tonal and visual ambience is set, one thinks it to be the work of one lone auteur.

Bly Manor, I suppose, could be seen as the greatest triumph of single-minded resolve in collaborative filmmaking, where every director, every writer, looked and felt like the one before and the one after. There’s certainly a welcome synchronous consistency of atmosphere and pacing in the series. However, at the same time, it makes me wonder about the worth of an individual filmmaker’s personal stamp on the project — especially if the overall mood of a singular vision is this staunchly preserved in the series. To put it bluntly, would Flanagan adhere to, say, Steven Spielberg’s style of directing and camera movement throughout the series, if the series was shepherded by the former — and if he did, would he personally not feel constricted?

But there are always two sides to everything, and this conversation is best left for another day, because despite the control (or because of it) Bly Manor comes out as nothing short of brilliant.

As the story goes, a woman in her mid-50s and with smartly dyed white and black hair (Carla Gugino) attends a rehearsal wedding of a young couple. When select members of the family sit in the lounge, the woman tells them a story, forewarning them that it would be a long one.

In 1980s London, a young American named Dani Clayton (Victoria Pedretti) applies for an au pair’s position in a newspaper advertisement (an au pair is a foreigner working as a governess-cum-helper for the host family). Her interviewer for the job is the businessman Henry Wingrave (Henry Thomas; The Haunting of Hill House, the young lead from E.T. — The Extraterrestrial). Henry, who prefers solitude in his office, is the children’s uncle, and there’s something peculiar about him.

Eternally shaken as if fighting his own inner demons, Henry initially rejects Dani for the position, only to hire her later in the day when he meets her at a pub. Here she asks him the million-dollar question: why has an easy-to-fill position for a wealthy business family remained open since the last six months? “What’s the catch?” she asks — a question he forced on Dani during the interview. As it turns out, there are two.

For Henry, the catch is superstition. The children’s parents have died while vacationing in India, and their last governess, a beautiful young woman named Rebecca (Tahirah Sharif) was found dead in a lake by the house. For Dani, the catch is that she doesn’t want to go home. Dani, it also seems, is a magnet for the occult. Every so often she is haunted by the spectre of a dark silhouetted man wearing big, bright, circular-rimmed glasses, who appears behind her whenever she looks at the mirror.

The children, the aforementioned Flora and her older, shockingly mature, brother Miles (Benjamin Evan Ainsworth), contend with their own set of hauntings. Still, like the adults in the house, they’re mostly cool about it.

Flora, who is first seen talking to the air near a marsh, leaves small crudely made dolls everywhere in the house. When asked, she often responds by saying everything is “absolutely splendid.” When not loitering, her gaze is transfixed behind the people she is speaking to.

Miles, on the other hand, has been rusticated from his school for brawling with sympathetic classmates, and killing a pigeon on the church’s altar.

While Flora’s quirks are evident, Miles’ mannerisms require the audiences’ attention.

Actually, there are many small things that either require or capture one’s attention throughout the nine-episode run.

Ambiguousness and mysteries, however, aren’t the screenplay’s forte, nor is it the intent of the producers. Answers are spelled out very clearly to nearly every question the narrative sets up, and, as if that weren’t enough — and it isn’t — uniformly perfect performances by the cast gets the message through, no matter how simple-minded the viewer is.

At first the people in the series seem stereotypically thought up, and morally black and white; they’re not.

Peter Quint (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), is Henry’s ambitious assistant and, from his first entry, we know he has his own interests in mind. Meanwhile, at the house are three supporting characters — a housekeeper, a cook and a gardener (T’Nia Miller, Rahul Kohli and Amelia Eve). One assumes them to be supporting characters, that is. But each character has its own emotional arc that intertwines seamlessly with the overall story, as if they’re a part of the same DNA strand.

As in the case of The Haunting of Hill House, every character, even the ghouls, get ingeniously made dedicated episodes to flesh out their end of the story.

With every passing episode, the series creates a bigger gap between its perceived and actual genre. By its fifth episode, Bly Manor forswears its guise of a horror series by embracing the gothic-romance-drama setting of the story.

As the series reaches its highpoint, and time and space start folding in on characters (a carryover trope from Hill House), we somehow begin sympathising with the children and adults. Even though everything seems dire and ghastly, the way Bly Manor is made — and especially with the way it climaxes — the only thing this writer can say is that “it is absolutely splendid.”

Streaming on Netflix, The Haunting Of Bly Manor is rated 16+. There are brief scenes of romance, and some harrowing scenes of dread, but nothing frightful

The Trial of the Chicago 7

Intention and obstacle. These two words are the fuel that drive screenwriter — and now director — Aaron Sorkin’s craft. Highlighted in Sorkin’s screenwriting lectures on Masterclass — an education website where professionals Ron Howard, David Mamet, Martin Scorsese and Steve Martin off-handedly teach their craft during interview-esque sessions — we get to see both intention and obstacle in unabashed, glorified vivacity in every passing moment of The Trial of the Chicago 7, streaming now on Netflix.

The idea of this screenwriting principal is this: every character has an intention, and every intention is faced with an obstacle. Although a drama — and a historic real-life event from 1968 at that — it would be unwise to think that real people’s lives from recorded history could use a bit of creative writing, but here it is. Rich, over-the-top and filled with one zinger of a dialogue after another, yet rarely fabricating stuff out of thin air (FYI, Sorkin wrote A Few Good Men, The West Wing, The Social Network and Moneyball, so the brilliant dialogues were always a given).

Originally commissioned by Steven Spielberg in 2007, who had an interest in the idea as a director, the project was shut down amidst budget concerns, and resurrected recently with Sorkin taking over the directorial duties. The years of rewriting may have made the screenplay tighter, and pointedly political.

In 1968, eight individuals were accused of a conspiracy to incite riots that had broken out during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Amongst the eight, five really mattered. Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne), one of the founders of the Students for a Democratic Society, the notorious founding members of the Youth International Party (aka Yippies) Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin (Sacha Baron Cohen, Jeremy Strong), the pacifist leader of National Mobilisation Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE), David Dellinger (John Carroll Lynch), and Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), a leader of the Black Panther Party.

It takes mere minutes to know that both the government of the United States at the time, and Sorkin, mean business. The group, with their own differing ideologies of protesting the Vietnam war, had gathered in a public park with a crowd of 10,000. As the film boomerangs between the group’s trial a year later and the past, one could see from their cases’ opening argument by the federal prosecuting attorney (a brilliant Joseph Gordon-Levitt), that they were set up by the justice system.

Judge Julius Hoffman, the presiding judge (Frank Langella, deserving an Oscar nod), is a racist who doesn’t care to listen to reason, no matter how hard, or how legally sound the defense attorney makes up the case (Mark Rylance, another pitch perfect performer in the ensemble).

Sorkin’s film is unrelenting and serious, highlighting issues of war and peace, democracy and order, justice and racism in one fell swoop. Every argument is built on hard-hitting punches that shake and rattle the justice system — and every bit synchronises with the current parallels in America. The story, however, rarely looks into the character’s personal lives. Sure, the case itself is mesmerising enough to fill in the entire two-hour-long running time, but some fleeting personal moments would have grounded the story much more than the political hoo-ha.

Still, The Trial of the Chicago 7 is a mesmerising account, whose shortfalls — no matter how trivial — only creep up on you long after the credits roll.

Streaming now on Netflix, this Oscar hopeful is rated R for mature themes, brief displays of alcohol, drugs and violence and gore

Published in Dawn, ICON, November 1st, 2020

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.