ABOUT two decades ago, this writer came across an elderly English couple at a hotel in Swat. We seemed to have already struck up a friendship and sat down to have a conversation over dinner the next evening.

They had been teaching at a Bahawalpur school for a brief period and had decided to visit Gilgit and Swat before heading back to their country. The old man seemed to be especially interested in Urdu poetry and asked “Is ghazal the only form of expression in Urdu poetry?” My answer was “not at all, by no means”. But it made me wonder at the extent of popularity of ghazal that had made it the only Urdu poetic genre to an unsuspecting foreigner otherwise quite learnt.

Ghazal is Urdu’s most popular poetic genre and it has been so for ages, though it is under constant threat of being dethroned by ‘nazm’, or poem, and especially in recent years the ‘coup’ seems to be quite plausible. There may be a myriad of reasons for ghazal’s prolonged and extensive popularity. But it is a fact that ghazal has prospered at the cost of ‘nazm’ though the modern Urdu poem has wonderfully expressed many a theme and idea that ghazal could not, and cannot, express because of its limited horizon imposed by its narrow space and restricted rhyming scheme.

‘Nazm’ is an umbrella term in Urdu that encompasses many genres and forms. In Urdu, a ‘nazm’ may take different names that may indicate either form or genre. For example, Altaf Hussain Hali’s famous poem Madd-o-jazar-i-Islam is normally known as Musaddas-i-Hali, although it is a ‘nazm’ and ‘musaddas’ is not a genre but just a form. ‘Musaddas’, an Arabic word, literally means having six sides or six lines. Hali’s poem has six lines in each stanza, hence the name.

Sehr-ul-Bayan by Mir Hasan and Gulzar-i-Naseem by Pandit Daya Shankar Naseem are also poems, albeit very long, composed in a different rhyming scheme and in a totally different form known as masnavi. Interestingly, both masnavi and ghazal are forms and genres simultaneously. But the term ‘nazm’ includes different forms, such as ‘musallas’, ‘murabb’a’, ‘mukhammas’, ‘musaddas’ and genres as well. Some genres, such as ‘masnavi’, ‘marsiya’, ‘qit’a’ etc are also kinds of poems. This may be confusing to some students because many a ‘marsiya’, which means dirge or elegy, written by Anees and Dabeer have six lines in each stanza but they are normally not called ‘musaddas’, though they are composed in the form of ‘musaddas’. Both Hali’s ‘musaddas’ and Anees’s ‘marsiya’ composed in six-line stanzas are poems or ‘nazms’.

In other words, ‘nazm’ or poem is a term used in Urdu quite extensively and it includes genres some of which may be written in different forms. With the arrival of new standards and critical theories in the aftermath of the British taking over in 1857, Urdu poem began to take new shape, tone and mood. Soon the poets of Urdu were writing blank verse, also known as ‘nazm-i-ghair muqaffa’ or ‘nazm-i-mu’arra’. Then arrived ‘vers libre’, a French term that means free verse. It is known as ‘azad nazm’ in Urdu.

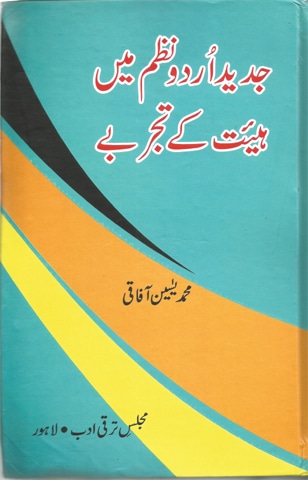

In the early 20th century and then in the post-Independent era, some new genres and forms were introduced into Urdu poetry. In the wake of modernism and post-modernism, we saw some experimentation with form and content. All these changes and developments demanded a detailed research work and Muhammad Yaseen Aafaqi just did that. His doctoral dissertation titled Jadeed Urdu Nazm Mein Haiyet Ke Tajribe (experimentation with form in modern Urdu poetry) discusses the forms or ‘haiyet’ (also pronounce hiat) and some new genres in Urdu poetry quite deeply.

Published by Lahore’s Majlis-i-Taraqqi-i-Adab, the book first explains what form or ‘haiyet’ is. Then it goes on to describe the historical background against which the writers of modern Urdu poem began experimenting and it includes the influence of the West, especially after the 1857 freedom war. The experimentation with the form by the writers of Urdu poem up to 1947 has also been discussed with reference to sonnet and the poetic works of some poets such as Noon Meem Rashid, Azamatullah Khan, Allama Iqbal, Tasadduq Hussain Khalid and some others.

Interestingly, it also takes into account some new genres and forms introduced into Urdu after Independence, such as haiku, ‘mahiyya’, ‘doha’, canto, triolet, limerick, ‘tarveeni’, ‘nazmana’, ‘kaafi’, ‘sanrio’, ‘tappa’ and some others.

The book includes two blurbs by Indian scholars, Prof Dr Abul Kalaam Qasmi and Prof Dr Shamim Hanafi, and they have admired the work quite generously. Indeed this 541-page research work, complete with ample citations and a huge bibliography, is admirable. It is a must-read for the students of Urdu literature. However, it won’t harm professors teaching Urdu at our universities if they read it, even if by mistake.

Published in Dawn, August 19th, 2019

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.