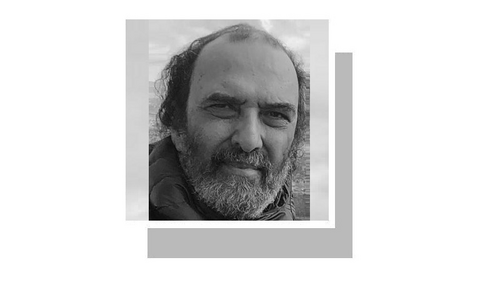

Avinash Paliwal teaches at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and is an alumnus of King’s College London and Delhi’s famed St. Stephen’s College. My Enemy’s Enemy: India in Afghanistan from the Soviet Invasion to the US Withdrawal is his doctoral dissertation in international relations.

Paliwal roots his investigation in the context of — as he and many Indian academics and policymakers see it — India’s emergence on the international stage as not just a regional, but a global power, given its two decades of significant GDP growth and its growing ties with the United States. As the author sees it, India’s rise in the global hierarchy occasions a need to understand its foreign policy formulation processes. For this, what could be more interesting, and less researched, than India’s relationship with Afghanistan, a state with which it once shared borders, whose history is inextricably linked with its own, and which now lies on the periphery of a region that India seeks to dominate?

The key question is: does India really have a legitimate role to play in Afghanistan, or is its interest in the country driven primarily by its need to contain Pakistan?

Why is India so keen to develop good ties with Afghanistan?

For most of us in Pakistan, the immediate reaction to any mention of India in Afghanistan is to contend that India is politically irrelevant to our western neighbour, and that the international community acknowledges that it is Pakistan — notwithstanding allegations of undue interference in Afghanistan’s domestic politics — which holds the key to bringing peace to that unfortunate land. India’s interest in Afghanistan is driven solely, we would assert, by its need to use any avenue it can find to destabilise sensitive areas in Pakistan. Given Pakistan’s contentious history with Afghanistan, India seems to be playing the classic game of “my enemy’s enemy is my friend.” It is this widely held belief that the author alludes to in the title.

However, Paliwal is at pains to point out that it may not be as simple as that. He posits that India’s relations with Afghanistan depend on three “drivers”: the desire to strike a balance between Afghanistan and Pakistan (and not let Pakistan dominate its western neighbour); the international political environment (and how it currently sees Afghanistan); and domestic Afghan politics. These three factors, according to him, dictate whether it is the hawks or the doves in the Indian establishment who get to dictate India’s policy towards Afghanistan. For the purposes of Paliwal’s theoretical model, the hawks are the partisans, or those who believe that all factions in Afghanistan who are even remotely sympathetic to, or allied with, Pakistan should be held at arm’s length by India. The doves in this model are also called conciliators, or those who are highly pragmatic and believe that India should attempt to have good relations with whoever is in government in Afghanistan, without consideration of their links with Pakistan. Paliwal traces the history of India’s relations with Afghanistan from the time of the former’s independence to date, using this form of analysis, ie how the three drivers of the policy were positioned, and which faction’s view gained ascendancy as a result.

The premise is interesting, but Paliwal tries too hard to make real life fit into his model. Rarely do the three drivers align, yet Paliwal explains away these contradictions by simply saying that one of the drivers was ascendant compared to the others. For instance, when explaining India’s tacit support for the Soviet invasion in spite of its strong non-aligned stance, the grassroots opposition within the country and the stance of the international community, he says that India’s policy was determined by the “evolving international political environment,” but does not make a very convincing case for why India misread the situation so badly and ended up on the losing side.

Similarly, Paliwal points to how the conciliators gained the upper hand during the early days of the Mujahideen government (1992-1996), thanks to the efforts of then prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao. But his explanation that this change of policy was influenced by India’s need to maintain a balance between Afghanistan and Pakistan tells only part of the story. In the same chapter, Paliwal himself points out that India’s recognition of former president Burhanuddin Rabbani’s government was driven by the realisation that India would have been isolated in western Asia had it not engaged with that government. India’s antipathy to the Taliban regime is explained by the regime’s international image, which is plausible, while its close engagement with former president Hamid Karzai and current president Ashraf Ghani is explained by the “keeping a balance” tack.

In effect, though, Paliwal’s first driver, the need to keep a balance between Afghanistan and Pakistan, is remarkably close to the “my enemy’s enemy” doctrine that Paliwal spends much time trying to disprove. Keeping a balance, as discussed in the book, means that India tries to ensure that successive regimes in Afghanistan gain sufficient clout and support to deflect Pakistan’s persistent interference in Afghanistan’s domestic affairs. For all the reliance on models and explanations of which drivers were operative where, the reader comes away with the distinct impression that India’s Afghan policy is heavily influenced by its Pakistan-centric lens.

Paliwal had been a journalist before turning to a career in academics and he clearly has a nose for a good story. The book is therefore written in an engaging tone that holds the interest of the layperson or the ordinary reader. By virtue of its origin in an academic treatise, it is meticulously researched and referenced. That it is not fully convincing in its central premise, ie that there are many shades and nuances to India’s policy towards Afghanistan, does not take away from its value as an interesting read for a student of contemporary politics. Paliwal did not make it to Pakistan for his research and there isn’t much information on the electronic media about his interactions with Pakistani scholars, so it will be interesting to see how the book is received in policy circles in Pakistan and amongst Pakistani academics and practitioners abroad.

The reviewer is a research and policy analyst

My Enemy’s Enemy: India in Afghanistan

from the Soviet Invasion to the US

Withdrawal

By Avinash Paliwal

HarperCollins, India

ISBN: 978-9352772681s

400pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, December 24th, 2017