While the national population and housing census is long overdue and much needed, there is great flux in the three smaller provinces due to the influx and movement of refugees and displaced people

Small pie, big bites

The federal government’s overbearing involvement in the census and bypassing the CCI betrays the spirit of the 18th Amendment — once again, provinces and districts are being excluded from counting decisions despite a pressing need to document newer demographic trends and phenomena

Perhaps the Babylonian planners in Ancient Mesopotamia were better strategists than Pakistani bureaucrats of the 21st century. About 6,000 years ago, they not only conducted regular censuses but also kept records of all people on clay tiles. The main objective of this gigantic exercise of conducting a headcount was straightforward: growing enough crops to meet the food needs of the population.

Pakistan’s statistics about its people — linked with power-sharing in legislatures, resource distribution among federating units, preparing electoral rolls and urban planning — are often perceived to be unreliable. Indeed, the last census conducted in 1998 was delayed by seven years, and this time too, the lapse has been about 18 years.

The lack of an accurate database, in turn, causes lopsided development as population figures are a prerequisite for egalitarian power-sharing, equitable distribution of resources among the federating units and urban planning. In the absence of accurate statistics, a population census can be manipulated to maintain the demographic hegemony of one region over the others, or at achieving a larger chunk from an ever-shrinking pie of resources.

But the 2016 census is important for another reason: the state is gradually taking a new shape, realignment of state institutions is also underway, and the provinces’ relationship with the federation is also being recrafted. In a situation of such flux, there are great opportunities to set things right.

Present-day Pakistan sees lopsided development: very high in certain areas (on the basis of their population) but underdeveloped and marginalised in others, irrespective of the fact that those areas might be serving as a revenue-generating engine for the country. Put another way, the advantage of being able to generate revenue has been converted into disadvantage.

With the enactment of the 18th Amendment in April, 2010, 17 ministries were devolved to the provinces, thereby also increasing fiscal pressures on provincial administrations. In the six years since then, provinces are finding it difficult to run matters that were earlier the responsibility of the Centre.

For this reason, provinces want more financial support from the Centre but money in the Federal Divisible Pool — the fund where national revenue is stored — is also limited. Provinces can only lay stake to more money if they show that their population has increased.

But why the focus on population?

In modern day Pakistan, perhaps the greatest determinant of population increase at a macro, provincial level, is internal migration. It is for this reason that experts believe there is a need to strike a balance between rural-to-urban migration and provincial fiscal matters.

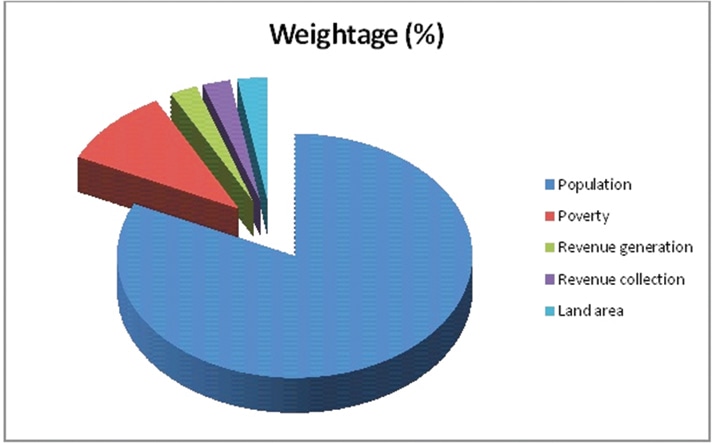

“Everyone presents an increased estimate of their population in order to get a major share in the Federal Divisible Pool. All groups want to show their majority,” explains Arif Hasan, founder of the Urban Resource Centre (URC). “For that reason, other categories such as population density, underdevelopment and revenue regeneration should also be given weightage in the Federal Divisible Pool.”

“Censuses in Pakistan have been politicised and there seems to be no plan to settle the demography issue through political will and intelligence work. There can still be technical flaws in the database, but the very nature of controversy needs to be settled politically in the true spirit of federalism,” argues Prof Syed Jaffar Ahmed, director of the Pakistan Study Centre at the University of Karachi.

According to the professor, the roots of the demographic controversy in Pakistan lie in the formative phase of the country, when the founding fathers sat down to chalk out power sharing mechanisms.

Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Bogra had presented a solution calling for a bicameral system, with the federal legislature comprising equal seats for the two wings. But just before the Bogra formula was to be passed by the National Assembly, Governor-General Ghulam Muhammad dismissed his government.

The controversy continued with the One Unit plan. All four provinces in West Pakistan were merged into a single unit in March 1955 as the government sought achieve “political parity” between the two wings of the country. Historians have argued that the plan sought numerical strength for the western wing, and convert the demographic majority of East Pakistan into a minority.

“The 1956 Constitution centred on the idea of political parity and the unicameral legislature was elected with 150 MNAs from East Pakistan and the remaining 150 from West Pakistan. The Bengalis created an uproar and agitated against the parity. The uproar resulted into the imposition of first martial law in the country,” says Dr Ahmed.

The PSC director was of the view that population became the sole criteria in the distribution of the NFC Award after East Pakistan parted ways with the western wing. Before 1971, he says, the distribution of resources was not carried out on the basis of population because that would have resulted in a larger share for East Pakistan.

“When East Pakistan was part of Pakistan, revenue generation was the criteria for resource allocation and not the population. It continued to be so under the same system till the 1973 Constitution, which handed over resource distribution to the National Finance Commission (NFC),” he says.

“Pakistan is a country where massive demographic shifts have reshaped the socio-economic structure. It has also provided unelected leaders with an opportunity to exploit. Instead of understanding shifting demographic dynamics and to tackle it in a prudent way, bureaucrats who had taken over as rulers let the matter become a problem,” concludes Dr Ahmed.

Centre versus CCI

The landmark 18th amendment abolished the Concurrent List, devolving the administrative responsibility of 17 ministries, departments and divisions to the provinces. But holding a census was never decentralised even though it should be carried out in collaboration with local authorities. Even today, the entire process is finalised in Islamabad.

Perhaps it is for this reason that the late prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, while commenting about the 1998 census in the National Assembly, once quipped: “When things come to Islamabad, they are cooked up and somebody else takes the broth.” It is because of the excessive centralisation of collecting data that past censuses were deemed controversial.

But the matter isn’t just about the centralisation of data collection; it is a larger issue about the role envisaged for provinces in the federation as well as about how various provinces interact with each other on questions of scarce resources and limited finances.

Human rights activist Humerah Rehman, who is pursuing a case in the Sindh High Court about the Council of Common Interests (CCI) being given permanent oversight of the census process, says that no effective forum exists for provinces to debate their issues and reach a conclusion.

“First of all, a permanent secretariat of the CCI needs to be set up because it is a constitutional requirement. The census should be conducted thereafter, because this is the one way in which the fears of Sindh and Balochistan can be allayed,” argues Rehman.

“Almost all the past censuses remained controversial because they were conducted under dubious motives: that who should be counted and who should not be counted. For that reason the census results caused intra- and inter-provincial crisis,” she says.

Rehman was of the view that the people from other provinces are earning in Sindh, getting all benefits, jobs and using the province’s resources but sending their remittances to their ‘home’ provinces.

In the mainstream and often through the media, an impression has been created that the population census is an essential yardstick to determine the provinces’ share in the national divisible pool, in the allocation of seats in the National Assembly and provincial assemblies, quotas in educational institutions and jobs, and allocation of seats for women and minorities.

“The very impression created by the federal government that under the Constitution, resources are dependent on a census is tantamount to hoodwinking and defrauding the people of Pakistan,” says constitutional expert Barrister Zamir Ghumro. Instead, he leans on the side of Rehman’s argument about the CCI.

According to the 1973 Constitution (schedule IV, item no. 9 of the Federal Legislative List Part II) the census is the CCI’s subject; the CCI is the constitutional and legal body to supervise the process of census. “For this reason,” says Barrister Ghumro, “the promulgation of the General Statistics (Reorganisation) Act of 2011, which transferred the control of census to the federal government away from the CCI, amounts to the subversion of the Constitution.”

In essence, despite the fact that the 18th amendment devised a mechanism for resolving inter-provincial disputes, the federal government has failed to abide by the true spirit of the amendment. The Centre has also failed in resolving disputes under the CCI mechanism, choosing instead to arbitrarily impose decisions upon various provinces.

“Under Article 160 of the Constitution, it’s the NFC that must fix the share of tax revenue to be used by the federal government while the rest is returned to the provinces,” says Barrister Ghumro. “Distributing 82 pc resources on the basis of population is in flagrant violation and subversion of the Constitution.”

Because a major workload was shifted to the provinces through devolution — the subjects of education, health, law and order, criminal justice administration system, industries, agriculture and irrigation, water and power, housing, population, planning and development, trade and commerce within provinces, lands, excise taxation, works and services — it is obvious that the census data has to be largely utilised by them and hence the respective questionnaires’ are to be prepared by them.

“Censuses in Pakistan have been politicised and there seems to be no plan to settle the demography issue through political will and intelligence work. There can still be technical flaws in the database, but the very nature of controversy needs to be settled politically in the true spirit of federalism.

The federal government, meanwhile, only needs the headcount data for adjusting seats in the National Assembly, which could be provided to it by the CCI through the provinces.

Article 51(5) of the Constitution reads: “Seats in the National Assembly shall be allocated to provinces, federal territory of Islamabad and Federally Administered Territorial Areas (Fata) on the basis of the last census.” Similarly, Article 51 (3) calls for the delineation of constituencies in accordance with the preceding census.

Barrister Ghumro explains that nowhere does the Constitution provide provisions for increasing or decreasing the number of National Assembly seats. “The federal government, as per the current constitutional scheme, should have six ministries and for such a meagre number of ministries, the number of National Assembly members must be restricted to 100, instead of 342,” he says.

Meanwhile, Arif Hasan offers the solution of devolving resource distribution at the district level. “This would result into development of districts and people would not need to migrate to urban areas” he says.

Hasan explains that migration is taking place because of underdevelopment of certain areas. He wants to see special funds for underdeveloped areas so as to bring them at par with developed areas. When asked about the percentage of district funds, he says it should be negotiable and assemblies should pass law about allocating budgets for districts.

“The unjust allocations of funds at the central and provincial level obstruct development at the local level,” he contends.

Refugees and illegal immigrants

The Supreme Court observed on Sept 19, 2013 during the Karachi case that over 2.5 million aliens were living in the city. It also pointed out a mechanism for registering aliens, but the government took no action to register them. There are always concerns that illegal immigrants have been counted as citizens while the indigenous people have been ignored.

All the governments during the past six censuses compromised an objective reality at the altar of political expediency. It has been noticed that some parties patronise these illegal immigrants and get CNICs for them as they can vote for them.

“The issue of migrants can’t be resolved merely by excluding them. They need to be registered and dealt as per the law,” says Arif Hasan. “There are concerns for all communities living in Karachi; those that migrated and those who were already living in Sindh in 1947. But to allaying Sindhi fears, it is important to note that the latest migration trends show a massive influx of Sindhis and Seraikis into urban areas. In the coming decade, Sindhis would comprise a sizeable population of Karachi.”

A high-level meeting attended by the officials of the National Database & Registration Authority (Nadra), National Aliens Registration Authority (Nara), Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), the Ministry of Interior, Sindh Home Department, Sindh Police and other departments concerned says that there were about 1.3 m illegal Bengalis and Burmese in Karachi. “The estimated number of Bengalis, mostly settled in Karachi, was said to be 1.1 m, while reportedly, there are 0.2 m Burmese.”

The Supreme Court and parties summoned during the Karachi case agreed that knowing exact number of aliens is necessary because some criminal gangs survive among them. Later, it was established that all attackers, facilitators and financiers involved in PNS Mehran, Jinnah International Airport, Safoora, French engineers and Daniel Pearl cases had come from other provinces.

Because of past enrolments of aliens as citizens thousands of aliens, according to sources in Nadra, have obtained CNICs. The separate enumeration of refugees and illegal immigrants has always been ignored and their registration as citizens in the census has allowed them to get CNICs and passport.

“Excluding outsiders from the census should have been the most worrying part for the government. But there seems to be no arrangement for enrolling aliens separately,” says Rehman.

Even the UN laws say the aliens be counted as refugees, migrants and immigrants and not as citizens. During 1998 census, secret lists were prepared by home departments of all provinces and an attempt was made that all outsiders would be excluded from the database for citizen.

“Demography is sacrosanct. There can’t be unchecked flow of aliens into historic lands and rights of indigenous people can’t be trampled upon,” says Rehman. “Across the world, there are rules stipulating illegal immigrants’ separate enrolment, since they are using resources allocated for indigenous people. They should only be registered and not given citizenship or permanent residence.”

There are suggestions that a separate census be carried out for migrants and refugees to know their exact number. In 2004, a tripartite agreement was signed between Afghan Commissionerate and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Population Census Organisation. According to census report for refugees compiled in 2005, over 3m Afghans resided in Pakistan.

There are two types of refugees; one registered as refugees and others who have not been registered. Those not registered can be identified with the help of Nadra by tracing their family tree and B-forms. When they are identified their CNICs and passports can be forfeited under the law.

Trans-provincial migration

Concerns have been expressed about the double registration of citizens — one at their place of origin and the second in their adopted abodes, when they move to urban areas. There are calls for excluding people from other provinces from the upcoming population census. However, if they are not counted in Karachi for example, they will still be using the resources of Sindh.

Sindhi nationalist parties say that there should be no citizen and voting right for all outsiders who have migrated to Sindh. They should not have the right to own properties, as is the case in India. Otherwise, they fear, non-Sindhis will be deciding the fate of Sindh.

The counter-narrative by some other parties is that if they are excluded from the census and not counted as the citizen of Sindh, it will affect the allocation of resources and wheat for the province. For example, the federal government allocated 896,000 tons of wheat for Sindh as per the 1998 census on the basis of the province’s 29.99 m population. It was 50,400 tonnes less wheat than the previous year. This caused a price hike and flour crisis in Karachi.

Arif Hasan says that urban problems have amassed because of the lack of the decision making on the part of the political parties. Political consensus is needed through negotiations. Rejecting the notion of conflict among different ethnicities, he claims that “only a sense of deprivation and inferiority complex of communities create fears. And this fear needs to be removed by giving special funds to underdeveloped areas and marginalised communities.”

There are also demands that the provinces be given a constitutional guarantee like those given by Indian Constitution Articles 370 and 371 to Kashmir, Goa and Nagaland about stopping the unchecked influx and buying properties by the aliens. In India, for example, non-Assamese are not allowed to vote in the state. “Such an arrangement can be made in Sindh and Gwadar,” resolved participants at a recent multi-party Sindhi nationalists’ conference in Karachi.

“In Pakistan, people’s mobility is free and lawful. There are no legal restrictions on migration,” explains Arif Hasan. “But the demography issue needs to be tackled seriously. Karachi is a non-Sindhi city and capital of Sindh. There should be rights of all with a legal cover. Even immigrants have their rights. Here the citizens have no rights.”

About increased tension among Karachi’s communities, he says: “Bombay is a non-Marathi city. There is a sizeable Punjabi population in Delhi. There were also ethnic issues but the political leadership in India resolved these issues. Similarly Karachi’s demography has changed. What’s lacking is that the province’s political leadership has not resolved people’s issues related to health, housing, education and transport.” He suggests digitising databases in order to maintain accurate population records.

Dr Jaffar also seconded the concerns expressed by the nationalist groups about attempts to show the indigenous people into a minority. “There can’t be ethnic cleansing to get rid of a problem; issues related with demographic changes need to be settled amicably,” he concludes.

Another major controversy is that who should conduct the census. A multi-party conference (MPC) called by the Sindh government says that “a census commission is supposed to have equal representation from provinces. As such, the commission is controversial.”

It is important to note here that all members but one in the National Census Commission’s governing body belong to Punjab. The MPC demanded that the provinces be given representation in the body because Sindh is getting a lesser share for want of census. “A just distribution of national resources is possible only when census is held in a transparent manner,” Chief Minister Qaim Ali Shah said at the occasion.

The MPC says that “if true figures are collected, Sindh would show a population many times higher than had been established through a flawed census.” The conference also resolved that three days was insufficient time to conduct a census and suggested 10 days for house count and 30 days for the headcount.

The writer is a staff member.

He tweets at @manzoor_chandio

Tug of nationalisms in Balochistan

The tussle in Pakistan’s largest province revolves around whether the Baloch are still a majority in their land

Much like in 1998, a tug of war is again taking place between Baloch and Pakhtun nationalists over holding the census in Balochistan.

Baloch and Pakhtun people have historically lived side by side in Balochistan for centuries; the two communities can be said to have a rivalry with each other but not a conflict. The census, if it goes ahead, will decide three key matters that are often the bone of contention between the two communities: competition for jobs, political power and economic opportunities.

This time around, it is not only the hard-line Baloch nationalists and resistance groups that are adamantly opposed to the census but also moderate Baloch nationalists and political parties. Terming it a conspiracy to convert Baloch population into a minority in their own province, they cite three reasons behind their opposition to the census.

First, they argue, there are four million Afghan refugees in Balochistan who arrived in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. More refugees have poured in after the American invasion in 2001. Besides the Pakhtun-dominated districts and Quetta, the provincial capital, Afghan refugees are also settled in two Baloch-dominated districts, Chaghi and Nushki.

“Baloch nationalists claim that over 80 pc of Afghan refugees have Pakistani national identity cards; they are registered on the voting lists; they have the passports; they have become the citizens of the country,” explains Shahzada Zulfiqar, a senior journalist based in Quetta.

According to some media reports, Afghan refugees have also been issued national identity cards and local domicile certificates. In 2015, Provincial Home Secretary Akbar Hussain Durrain presided over a meeting where it was decided that Afghan refugees’ identification cards and domicile certificates will be checked again.

Baloch nationalists fear, therefore, that Afghan refugees will be counted as an indigenous part of Balochistan in the upcoming census, thereby skewing demographics.

The nationalists’ second argument against the census revolves around displaced Baloch: in the 2010 floods, thousands were displaced from Nasirabad and Jafferabad, both predominately Baloch districts. People were forced to migrate away from Dera Bugti too after the military launched an operation in 2006. The fate of the displaced hangs in the balance.

Third, they fear that the Baloch will not be counted in volatile districts of the province, including Kech, Panjgur, Turbat, Gawadar, and Mastung. This apprehension is based on voter turnout in the 2013 general elections, which remained low Moreover, Baloch people have reportedly also left their abodes in Makran division, Awaran, and Kharan due to the prevailing security situation.

On the other side — the ones in favour of conducting a census — are Pakhtun nationalists from the Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party (PkMAP), the largest Pakhtun-nationalist party in Balochistan, and parties hailing from predominantly Pakhtun districts in northern Balochistan. Most complain that they do not get equal rights in Balochistan; they argue instead that “everything in Balochistan” should be divided equally between the Baloch and Pakhtun.

A case in point is Maulana Abdul Wasay, who is from the Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam - Fazl (JUI-F)and opposition minister in the Balochistan Assembly. He recently stated in a Quetta-based local newspaper, “We are in favour of a census so that Balochistan may get its rights; Baloch people should not become obstacles in its way.”

Notwithstanding the irony in that statement, the tussle between the Baloch and Pakhtun is rooted in history and is often politically charged.

The refugees question has implications beyond the Baloch and particularly for the Pakhtuns: if Afghan refugees in Pishin, for example, are counted as Balochistan nationals, the Pakhtun population numbers might increase. But simultaneously, they will eat into resources and seats allocated for Pakhtuns settled in Balochistan.

The rivalry commenced in the 1970s, when Pakhtun nationalist leader Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai was given a cold shoulder by the National Awami Party leadership in Balochistan. Achakzai did not enjoy cordial relations with Mir Ghous Bakhsh Bizenjo, who became Balochistan’s governor, and Sardar Attah Ullah Mengal, who became the chief minister. To this day, the rivalry finds new ways to reinvent itself.

In 1998, when Sardar Akhtar Mengal was Balochistan’s chief minister, the PkMAP resisted and opposed the census. They had reportedly said that the coalition provincial government in Balochistan, which was led by Sardar Akhtar Mengal, would not conduct census in a transparent way. They boycotted the census, only to realise later that their boycott dented Pakhtun interests in the province as they were under-counted in the census.

In recent times, PkMAP chief Mehmood Khan Achakzai took to task the chief of National Party, Mir Hasil Khan Bizenjo, at a CPEC meeting in Islamabad. Bizenjo had said that he feared more Pakhtuns would come to Balochistan in search of jobs, squeezing the Baloch population even further. He had also wanted the issue of Afghan refugees and unregistered Pakhtuns to be settled before the census.

But Mehmood Khan Achakzai interjected Bizenjo over the question of Afghan refugees, sarcastically quipping, “By repatriating Pakhtuns to Afghanistan, you mean to say all of us Pakhtuns sitting in the meeting should also leave the country?” Pointing towards Asfandyar Wali Khan, Aftab Sherpao and Pervez Khattak, Achakzai had said all had their roots in Afghanistan; did Bizenjo want to send all of them back to Afghanistan?

But the refugees question has implications beyond the Baloch and particularly for the Pakhtuns: if Afghan refugees in Pishin, for example, are counted as Balochistan nationals, the Pakhtun population numbers might increase. But simultaneously, they will eat into resources and seats allocated for Pakhtuns settled in Balochistan.

It is important to note here beyond the bickering, Pakhtuns have had representation in government since long and have always shared power with the Baloch. For example, in present times, the governor is a Pakhtun who belongs to the PkMAP while the chief minister is a Baloch from PML-N.

Interestingly, a district-wise analysis of Balochistan’s Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) shows that in terms of land area, Pakhtuns are settled in about 10 pc of Balochistan. Every PSDP, however, allows the Pakhtuns a greater share in resources than the Baloch. Similarly, the status quo in Balochistan is that Pakhtun share in public jobs and opportunities is also more than that of the Baloch.

And yet, with the CPEC opening new debates around who stands to benefit, Baloch voices have provided the stiffest opposition to the project, fearing that they’ll become a minority in their own province.

For the development of the Gwadar port project, argue Baloch nationalists, a large number of people might come to Balochistan from other provinces and will outnumber the local and adjoining Baloch populations. Senate Chairman Raza Rabbani had acknowledged the apprehensions, and proposed that it was needed to explore possibilities to make legislation to the effect that the new arrivals will not be able to vote in Gwadar.

Meanwhile, sources close to PML-N claimed that Mehmood Khan Achakzai, before the installation of Sanaullah Zehri as chief minister, had told him that his party will only back his candidature if he conducted a census in the province. CM Zehri had acknowledged this condition back then.

The census is also the reason why Achakzai started showing his opposition toward former CM Dr Abdul Malik Baloch, because he had been writing letters to the federal government to cancel holding the census in Balochistan since the situation was not suitable.

But ultimately, the responsibility of removing reservations of the Baloch people about the census lies squarely with the federal government. It is unreasonable to expect a historical dispute to be settled by the very people who are party to the dispute. An external arbitrator is needed, and the federal government needs to play its role in making Balochistan count.

The writer is a journalist and researcher.

He tweets @Akbar_Notezai

Count Fata out

by Zulfiqar Ali

With Operation Zarb-i-Azb still in progress, any meaningful census in Fata cannot be conducted until the displaced return to their homes and lives

Debates over the intricacies of the census are a luxury in the remote, war-torn Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata).

While the rest of the country mulls over the merits and demerits of how the census is being conducted, Operation Zarb-i-Azb is still in progress in North Waziristan Agency. Many areas of South Waziristan, Khyber, Orakzai and Kurram agencies are grey areas. Several pockets in Bajaur and Mohmand agencies along the Afghan border continue to be troubled.

Despite the pressing need for a census, the current situation in Fata has turned the issue into a non-starter.

Officials of the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) have also received a categorical answer from military commanders that holding a census in Fata in the present circumstances is not possible.

“The army’s response was not encouraging and they (commanders) believed that the current security situation was not favourable towards a headcount in Fata,” says one official in PBS office, who recently attended a meeting with security officials in Peshawar.

“Without the army’s support, a census is not possible in Fata; but involving soldiers in the exercise may pose threat to enumerators, so we are in double jeopardy,” he says.

In the embers of a war that has spanned more than a decade now, massive displacement has already taken place and is only slowly reversing. Till now, the government has managed to send home around 285,000 displaced families but more than 162,139 registered families (1.2 million individuals) are yet to be repatriated to their areas in Fata. These displaced families are still living in various towns and cities of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, Punjab and Islamabad.

A large numbers of tribal people who did not get themselves registered with government agencies as internally displaced persons have either temporarily or permanently migrated to the country’s urban and semi-urban areas due to insecurity or economic disparities.

While they have been away, settlements have been destroyed and commercial properties turned into rubble. The civil administration has been left handicapped, and security concerns still loom large.

In the embers of a war that has spanned more than a decade now, massive displacement has already taken place and is only slowly reversing. Till now, the government has managed to send home around 285,000 displaced families but more than 162,139 registered families (1.2 million individuals) are yet to be repatriated to their areas in Fata.

Roughly 7,000 shops have been demolished in Miramshah Bazaar and around 4,000 in Mirali, the second largest town of North Waziristan Agency. Areas of South Waziristan Agency, in Kurram, Orakzai and Khyber Agency, which were dominated by the Mehsud tribe also show the phenomenon, where thousands of houses and villages are now just rubble.

“How will an enumerator verify ownership of a house in Miramshah or Mirali when the owner is residing in Bannu, Peshawar or Karachi?” argues an official in Fata Secretariat. As he explains, enumerators could not reach all areas to collect housing data in 2011 either, as security and logistical problems made it impossible to do so.

Were the government choose to go ahead with a census in Fata, the first problem it’d encounter is house listing. Years of military offensives in the area have resulted in widespread destruction of property; there simply isn’t much to count.

The decade-long strife due to militancy has altered both the landscape and the demographic structure of the tribal borderlands. Millions of people were forced to flee their homes and move to settled areas of the country; in addition, over 100,000 people of North Waziristan Agency took refuge in Afghanistan when the last operation started in June, 2014. The UNHCR reports that 21,000 Pakistanis are still living as refugees in Afghanistan.

“The entire population data will be faulty if the government goes for conducting census in Fata in these circumstances,” observes one senior functionary at the Civil Secretariat Fata. “You need to repatriate all IDPs, rehabilitate in their areas, reconstruct infrastructure, restore civil administration and then go for a census; otherwise, it will all be just a formality.”

Times were different in Fata when the house listing and population census was last conducted in 1998. There wasn’t any militancy, there was no displacement of civilians, no security problems nor was there any military operation.

And yet, the 1998 population census report became a laughing stock in official as well as political circles when Fata’s total population was reported as 3.18 m, with 2 pc annual growth rate. Due to logistical and administrative problems, enumerators were unable to reach every nook and corner in Fata to collect accurate data about the people living there and the number and kinds of houses they lived in.

Large scale displacement from the conflict-ridden parts of Fata also proved that the concerns and reservations raised over the 1998 census figures were not off the mark.

Take the example of the North Waziristan Agency: its total population in the 1998 census report was 361,246. At a steady 2pc increase in the last 16 years, the population should have stood at around 500,000. But presently, the National Database and Registration Authority (Nadra) has verified 104,002 registered families (approximately 832,000 individuals) who were displaced from only two out of eight tehsils of North Waziristan.

Clearly, the numbers involved are much greater and can only be ascertained through a fresh and comprehensive census in Fata.

A former governor was even moved to criticise the census report and reject figures from 1998. The previous population census report is not considered reliable in official circles either. Much like the 1998 census, officials admit that the house listing survey conducted in 2011 was faulty because enumerators could not get access to some troubled and remote areas of Fata. The process was postponed in some areas at that time.

The countrywide census this time around is being conducted in two phases. In the first phase, enumerators will carry out a house listing practice in three days. After the completion of this exercise, they will begin the headcount, which will take another 15 days. The PBS has divided the country in 166,801 house blocks. Each block comprises 200-250 houses. Under the plan, there will be one supervisor for each block to conduct house listing and headcounts.

Meanwhile, an official in PBS’ Peshawar office confirms that a separate pro-forma carrying details about IDPs, who are now officially called Temporarily Dislocated Persons (TDPs), has been printed. All 166,801 supervisors will be given this additional set of pro-forma for the verification of TDPs, wherever they may be settled in KP or any other part of the country. This is an additional set of responsibility, in addition to the headcount and house listing duties that they are supposed to perform.

“Our enumerators will distribute pro-forma containing particulars about TDPs during the census, apart from distributing Form-A and B,” he says, adding that this special pro-forma would help the government in collecting data about displaced population.

The official agrees that movement of enumerators and collection of census data will be a difficult task as compared to the previous exercise.

The writer is a member of staff.

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, March 20th, 2016

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.