The timing of British medical journal Lancet’s issue on Pakistan’s health sector could not have been better. With governance in Pakistan having recently changed hands, the four research papers in the issue titled ‘Health Transitions in Pakistan,’ undertake an analysis of the country’s health performance over the years and offer recommendations for the future.

The study, which was carried out keeping the 18th Constitutional Amendment in mind, especially points to the challenges and opportunities in the areas of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, and the increased burden of lifestyle or non-communicable diseases. The study makes a strong case for future health reforms by calling for universal healthcare with a focus on equity.

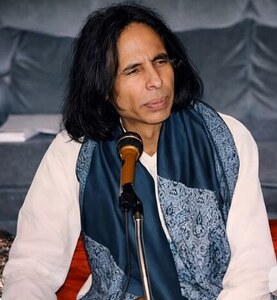

The research was headed by Dr Sania Nishtar, president of Heartfile, a think-tank for health policy in the country, and Dr Zulfikar A. Bhutta, director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health at the Aga Khan University in Karachi.

At the federal level, the study recommends increased investments in the health sector to at least five per cent of the GDP by 2025. At the moment, the investment stands at an abysmal 0.9 per cent. To make health a political priority and hold governments accountable, experts have suggested calling for an all-parties conference on health that seeks commitment for an “agreed set of actions”.

The recommendations made in these papers include increasing excise duty on cigarettes and using that revenue towards the prevention of non-communicable diseases and introducing nutrition as well as maternal, newborn and child health in the national income support programme.

The researchers also call for a national health policy that conforms to the 18th Constitutional Amendment and the establishment of a health division under the ministry of inter-provincial coordination.

What many do not know is that the burden of non-communicable diseases and injuries is quite high in Pakistan. Non-communicable diseases include diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. According to one of the papers, Pakistan is among the top seven countries with the largest number of diabetic people. Drawing attention to the huge economic toll of these diseases — approximately 232 million euros — the findings suggest not only further research into the ailments but also that they be made a national priority with policy, legislation and programmes developed accordingly. These should promote healthy diet and physical activity to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in premature deaths of individuals between the ages of 30 and 69.

But why should a British journal be interested in Pakistan’s health system?

With universal healthcare gaining traction, countries are trying to figure out how best to use limited resources and capacity to implement it. Therefore, there is an emphasis on putting health at the centre of nation-building and social welfare agendas.

Lancet’s editor, Richard Horton, lists a number of reasons why Pakistan’s health system received this attention. He terms Pakistan a “research productive nation” where public health practitioners have delivered important innovations through programmes such as community-based Lady Health Workers; health experts have made a “demonstrable difference,” both in Pakistan and internationally, in identifying the threat of non-communicable diseases in Asia; they have signalled the dangers of abolishing Pakistan’s health ministry; raised alarm about substandard medicines, and lastly, mobilised the Muslim world to end polio.

“The introduction of a new cadre of community health workers has had an especially important part to play in reducing stillbirths and newborn mortality, evidence that has had global reach,” Horton writes.

But a big question is whether the study has been noticed by those who can make a difference in the system. While it is too early to say if it has had an impact, Dr Bhutta is “very optimistic” that the new government will take note of the recommendations. “We provide a blueprint and a comparison of portfolios. We have done the needful in taking this forward by engaging political parties at various levels,” he says.

Additionally, all mainstream political parties have listed health as a priority in their manifestos. They recommend an increase in budgets, specially the PPP (five per cent of consolidated government spending), while the MQM and the PTI recommend four and 2.6 percent of the GDP, respectively. The PTI also promises a hundred per cent improvement in the existing public health sector coverage and the MQM 100 per cent coverage in vaccination and a 50 per cent reduction in maternal and infant mortality rates. The PPP aims to reduce population growth from two per cent to 1.6 per cent and to eradicate polio by 2015.

But, says Bhutta, “the devil is in the detail and implementation strategies.” He knows that far too often there remains a huge disconnect between policy and implementation. He also hopes that not only would there be greater political ownership of healthcare programmes with the new government but also importantly an end to “policy vacillation” that leads to changes in key programmes.

It is imperative that this volume of evidence be made available to policymakers, practitioners, researchers, the civil society and other stakeholders. For example, by implementation of several primary and secondary packages of care for mother and child — like the antenatal care, child care, post natal care, immunisation and nutrition — by year 2015 almost 58 per cent of maternal and child deaths, that are estimated to be about 367,900, can be averted, and 49 per cent of an estimated 180,000 stillbirths can be prevented.

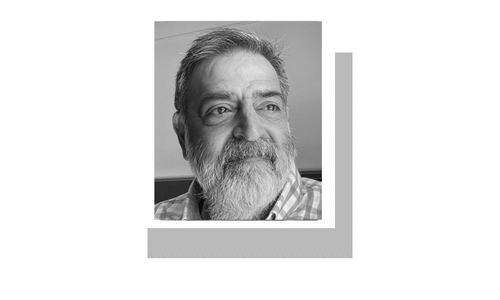

Doctor and demographer Farid Midhet was particularly disappointed to read about the lack of progress in mother and child health, despite several large-scale intervention programmes over the last decade. “I believe there is a need to sit down and analyse why things are not working in this particular area,” says Midhet.

Such an in-depth analysis, he says, would require looking into trends in new national demographic and health studies. “It would also help set guidelines for the government to steer the efforts of donors in this field, such as USAID, which is funding six components of the maternal, newborn and child health programme on an extremely large scale,” he adds.

According to Bhutta, improvements don’t always require huge investments but just the need to ensure that the existing public sector programmes are implemented.