Last month, the Sachal Jazz Ensemble did just that.

Combining western instruments with the eastern sitar, flute, sarod, sarangi, tabla and dholak, the ensemble of seven musicians from Pakistan, four from India and 16 from Britain played to a rousing crowd of over 900.

Jay Visvadeva, CEO and artistic director of Sama Arts Network – an art company that put the show up – seemed quite pleased with the response. “It was a complete sold-out performance and people who had not booked in advance had to be turned away.”

Sachal wooed the audience with 14 tracks, mostly jazz, interspersed with Brazilian as well as some original raga compositions in jazz style. The Pink Panther number, in particular, was delightful.

“It was very refreshing to see Pakistanis on stage – so beautifully removed from common images of Pakistan that people carry,” CNN-IBN Sanjay Suri correspondent.

While he thought some of the compositions were “most imaginatively interpreted and rendered”, he found an element of repetition.

“The concert could have been cut short. It was a pity that many people left early simply to catch the train,” he said.

The band members were, however, delighted with the response.

“I have never been happier” said Baqir Abbas, one of the performers. The 37-year-old flutist last played in London in 2011, with Indian folk singer Hans Raj Hans.

“This was totally instrumental.”

“The western musicians we played with were brilliant and the result was the most beautiful music,” said Abbas, beaming with pride.

Before every big performance, he said, musicians usually pray privately “in their hearts.”

This time, it was different.

“We formed a circle and made a collective prayer,” he revealed, adding that there was a feeling of camaraderie among the performers.

Abbas said everyone performed to perfection.

“Usually there are some moments where someone or the other falters; I can’t recall any of it happening this time.” The musicians in Pakistan had been rehearsing rigorously for this for over two months.

Little known at home, Sachal are nestled in an old quarter of Lahore, now invaded by car showrooms. The ensemble made sound waves internationally last year, with their eastern take of a 1959 jazz number “Take Five” by American Dave Brubeck’s Quartet.

The track found its way to the top of the jazz album charts on iTunes in Britain and the United States

“Sachal’s rendition of jazz in a new format through eastern instruments while remaining true to this form of music is what makes it so different,” explained Abbas.

Acknowledging that the tabla gave the eastern rendering of jazz a distinctive touch, Suri, however, felt “it was a little “overdone” during the performance that evening. He did not find the solo interludes “slipping harmoniously into the composition.”

“The tabla bols in Take Five, did not work at all. It quite ruined the piece everyone had been waiting for.”

Rosie Thomas, a social anthropologist and a pioneer of the academic study of popular Indian cinema, on the other hand, found the rendition of Take Five a “witty take” but felt in other tracks the “overkill of violins playing from sheet music, somehow, stifled the creativity of the musicians.”

While individually, music aficionados would know of Ballu Khan, Baqir Ali, Nafees Ahmed, Nijat Ali and Najaf Ali and even seen them perform with the greats of Pakistani classical and folk music, not many people in Pakistan are aware of the kind of music that is being produced by the artists collectively at Sachal Studios.

Izzat Majeed, 60, a businessman, who owns these state of the art studios, inspired by the Abbey Raod Studios in London, does not like to label the music produced at his studios. “It’s not hybrid, nor is it fusion” he says. He leaves it to terming it simply as “contemporary.”

His long-time friend Mushtaq Soofi, a poet, who helps run the studio after his retirement from state-owned Pakistan Television, explains they produce music for the love of it and definitely not for “commercial purpose”.

“We want to promote and support the traditions of music.”

They don’t work for anybody and nor do they rent the studios out to anybody, but Soofi says that Sachal members are welcome to work for anyone they please.

According to Munir Kaukab, their recording engineer, who would want to leave once they get hooked on to the kind of equipment and quality available at Sachal?

Dipankar de Sarkar, a London-based journalist who is also an amateur musician, in both Indian and western classical traditions finds Sachal’s innovations “fantastic.”

“It’s a landmark on a cultural highway to bridge the cultural divide,” he predicts, adding: “Best response to fundos!”

Having been with Sachal since it began in 2003, Abbas insists these studios gave a new lease of life to the dying “studio recording traditions” that prevailed from the 1940s to the 1990s, after which the computer invaded the music world.

“It’s the only studio in Pakistan where music is not manipulated by the use of computer,” he says. “Music is recorded in its purest form here.”

For many classical musicians, lost in the din of digital and electronic world of music, the Sachal Studios have given them a reason to play again as well as support them financially.

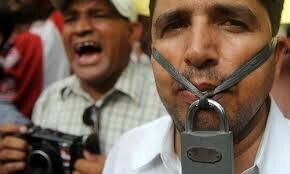

But music in Pakistan had been dying a slow death even before the onslaught of the digital decade.

“The Zia [during the 11years of Islamisation of General Zia-ul Haq’s –dictatorship] era saw the death of music,” says Majeed.

Riaz Hussain, 60, the music arranger at Sachal, laments the loss of “eleven precious years” during Zia’s regime, and calls the former president the biggest enemy of music. “He closed all avenues for us. He said music was haram [forbidden] in Islam.”

“With the collapse of the Pakistani film industry in the 1980s, many violinists, who made up a large part of the orchestra were rendered unemployed,” explained Abbas. And when rock and pop music were introduced, the violin was deemed inappropriate. “Many like Pappu, here,” he said, pointing to the white-haired cello player, had set up a tea stall and had given up the profession.”

When Sachal came on the music scene, they were able to dig out just ten violinists in the city; in nine years they have over 30 working for them.

Today, things seem to be looking up for many of the classical singers thanks to Sachal’s efforts.

They have even been approached by several international filmmakers to do a feature film on the studio and their endeavors towards revival of Pakistan’s classical music scene. Confirming this, Soofi said: “We’re open to these ideas.”

In a very short span, since the studio opened its doors to the music scene in Lahore, in 2003, it has produced over 30 albums spanning a spectrum of genres, from classical to ghazals, and local folk to amazing jazz. Unfortunately, these have not been marketed and not accessible to the people.

The author is a freelance journalist.