Estimates, forecasts and the budget are all very well if one wore fringes and bead headbands while looking into a crystal ball.

Every hope of a V-shaped recovery is contingent on there not being a second wave of Covid-19 while Pakistan is firmly in the grip of the first wave.

Another unknown is the possibility of the coronavirus mutating down the road the way the Spanish flu did when the second wave hit.

Much of the world is banking on a vaccine that may as yet not exist.

Short of a winged messenger bringing glad tidings, all talk of the growth rate and future prospects is just that: talk.

The PTI government’s (only) feather in the cap is the 71 per cent decrease in the current account deficit.

Hence a few across-the-board changes such as 2pc customs duty being abolished on 1,600 tariff lines and reduction of tariffs on raw materials and semi-finished goods fit the bill.

More specifically, a kaleidoscope of segments, from Quran publishers to button makers,has benefitted from the budget.

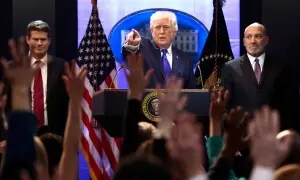

Trade, as we know it, had been changing before Covid-19 as the ‘leader of the free world’ Trump was one of the harbingers of bringing back the age-old notion of economic growth: import substitution.

Independently of the pandemic, many countries had jumped on this bandwagon.

Pakistan had made some hay, and was looking to make some more, when the US-China trade war started in the hopes of attracting some of the foreign direct investment in the textile sector.

There was some chatter about growing/importing soya beans to export to China, one of its biggest imports from the United States.

None of the plans bore much fruit before the coronavirus whammy hit. Going forward, Covid-19 can put globalisation into a coma, if not killed it, as suggested by some international analysts.

The pandemic will entrench a bias towards self-reliance for all global economies.

And is that a bad thing?

Even though Pakistan is a cotton grower and textile exporter, till last year one could find t-shirts made in Bangladesh in Karachi’s Zainab Market and baby rompers manufactured in India in malls despite the trade ban.

India is waiting in the wings to grab China’s slice of exports.

It has readied land twice the size of Luxembourg to offer companies that want to move their manufacturing out of China and has reached out to about a thousand American multinationals, reports BBC.

Clearly, Pakistan has been losing the international game.

But the pandemic has uprooted global supply chains and changed how the game is played.

It may be an idle hope but closed borders could force local industries to step up and deliver to domestic demand, leading to first domestic than global competitiveness.

Pandemic-induced protectionism may be this decade’s fad, but it could lead to an increase in domestic trade.

With an import-reliant economy for consumption and manufacturing, a high enough increase in trade within borders to offset the drop in exports appears so far beyond the realm of possibility that it is laughable.

As part of the Belt and Road Initiative, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor foresaw a world that took global trade to new heights, a vision that may have at least been put on the back burner till we are under the pandemic’s shadow.

Keep in mind that the aftershocks of the 2009-10 recession were still reverberating when the coronavirus reared its ugly head so there is no knowing when, or even if, the global economy will resume its pre–Covid-19, pre–US-China trade war levels.

Thus, the laughable must become conceivable, starting with the food bill.

The humble daal eaten in ramshackle houses belonging to those at the bottom of the economic strata is an imported product.

It is ludicrous that an agrarian economy had food imports of $4.5 billion, accounting for nearly 12pc of the imports, in July-April this fiscal year.

Edible oil, pulses and tea were the top three items and while growing tea leaves is not feasible, oilseeds and pulses can be grown if crops could be made less politicised.

By the same token, raw cotton is the top textile input.

Pakistan produces short- and medium-staple fibre raw cotton with a high trash content of 9pc as opposed to a global average of 3-4pc.

While domestic supply is fully utilised, global demand requires synthetic fibres and long-staple clean dry raw cotton.

With the exception of denim products where Pakistan is globally competitive enough to be part of Levi’s supply chain, apparel made from Pakistan’s cotton results in defected low-quality fabrics that are not usually printed or dyed.

Why can’t investment be made to improve the quality of local cotton instead of spending hundreds of millions of dollars each year importing it?

Together, edible oil, oilseeds, pulses and cotton imports clocked in at $2.8bn till April this fiscal year.

This roughly converts to Rs461bn (at the current exchange rate), an amount greater than the petroleum levy the government hopes to earn this year.

Why can’t the budget set aside a proportion of that amount to develop Pakistan’s domestic supply instead of playing around with subsidies and tariff lines?

The auto sector, which The Economist called “an absurdly protected industry” in 2015, has been an elephant in the room for some time.

With the contraction in the economy, its imports nearly halved this fiscal year though there has been the excitement of new players, fresh investment and higher domestic competition in the not-so-distant past.

It is debatable how much localisation each player achieved, but an inward-looking economy requires a renewed interest in a higher level of import substitution.

Pakistan cannot be self-sufficient like Cuba, North Korea or Iran, nor should it aim to do so. But a reduction in imports cannot be through the hammers of duties and a more expensive dollar alone.

History bears witness that regional export powerhouses, India and China, became competitive domestically before becoming forces to be reckoned with.

But these are realities that this budget, and all the budgets before, has ignored.

The measures necessary to bring about sweeping changes are not projects that deliver growth rates today.

Ours may not be the generation that will benefit but those of our children and grandchildren. But this philosophy does not guarantee re-election.

Hence, the government will toot the horn of the short-term reduction in the current account deficit, which will balloon again when times are better. And the future will be ignored once again.