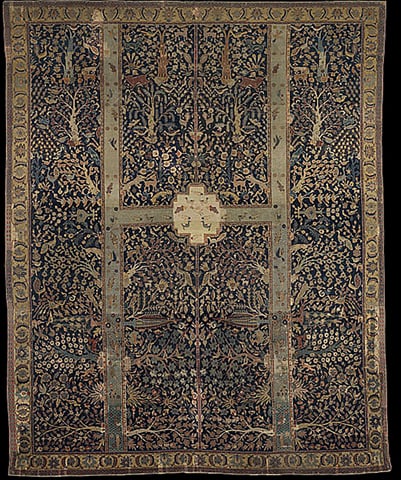

It is the lingering impact of unusual artefacts that makes viewing museum exhibits so worthwhile. It is for the same reason that the show Eternal Springtime: A Persian Garden Carpet, from the Burrell Collection currently on at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, piques interest. Looking at the ‘Wagner Garden Carpet’ is like discovering a new link to an old subject. Regal, intensely patterned but aged and sombre hued, this quiet exhibit invites reflection.

Gifted by Sir William Burrell to the city of Glasgow in 1944, this prized ‘Wagner Garden Carpet’ is considered to be one of the three earliest surviving Persian garden carpets in the world — the other two being at the Jaipur Museum in India and the Museum of Industrial Art in Vienna, Austria. Due to its large size and condition, measuring approximately 5.5 x 14.3 metres, it has only been displayed thrice in the last few decades.

Produced during the Safavid period in the 17th century Kirman — a well-known carpet-making city in south-eastern Iran — this carpet has a formal garden layout on a dark blue background. It is dominated by two long parallel water channels that are linked by a central pool and two short branch channels, all together forming the shape ‘H’.

The design of the ‘Wagner Garden Carpet’ from the Safavid era delights the eye and soothes the mind

The garden’s six rectangular sections are vertically symmetrical, with the right side of the carpet mirroring its left. The garden is filled with cypresses, flowering trees and shrubs, and populated with an array of birds, butterflies, animals and several types of fish and duck. Lions, leopards, gazelles, peacocks, storks and pigeons roam the garden too.

The layout of the flora and fauna gradually changes direction in the top half of the carpet, creating a panoramic view of the garden for the person sitting on it at the bottom half, a most unusual layout for this type of garden carpet. It almost invokes a heavenly-walled menagerie that immerses the person sitting on it in its natural but well-ordered world. Reminding the viewer of its cultural roots, its design was inspired by both the pre-Islamic Persian Paradise and the descriptions of the Garden of Heaven in the Quran.

As a relic, the ‘Wagner Carpet’ reflects the cultural history and art ethos prevalent during the Safavid era. Current art audiences sensitised to the rigorous regimen of miniature painting will be able to draw parallels between the imagery, layout and workmanship levels found in this carpet and the vocabulary, composition and precision lavished on the Persian miniature. The similarity in the garden format — as a space for repose, leisure or meditation or as a forested hunting ground — and the specific flora and fauna visualisations in the Persian miniature and the ‘Wagner Carpet’ is striking. Painted on wasli as a fine art creation or woven in silk, cotton and wool as a textile art product ,both mediums are underpinned by a highly disciplined, demanding work attitude. This also indicates that, be it art or craft, both disciplines were accorded the highest esteem in that era.

Under the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal dynasties, carpet-weaving was transformed from a minor craft based on patterns passed down from generation-to-generation into a statewide industry with patterns created in court workshops. In this period, carpets were fabricated in greater quantity than ever before. They were traded to Europe and the Far East where, too precious to be placed on the ground, they were used to cover furniture or hung on walls.

Within the Islamic world, especially fine specimens were collected in royal households. This manner of carpet production bears resemblance to the miniature painting workshop at the imperial Mughal court in the 16th century which was more complex in organisation than any atelier that India had ever seen. The Mughal workshop started out large and grew rapidly, so that a very heterogeneous group of about 50 artists in 1565 had by the year 1600 reached the unheard-of scale of about 130 painters.

The imagery of the ‘Wagner Carpet’ is a merry mix of garden and forest vegetation and an amazing variation of wildlife abuzz with life and activity. The title ‘Eternal Springtime’ relating to this bustle and motion provokes inquiry on the contexts associated with Islamic Gardens.

In the Persian paradise garden or Charbagh, the most important elements were water, sanctuary and shade which provided a refuge from the daily trials of nomadic desert life. Its form, copied in Persian carpet patterns, was based on the four rivers of life which divided the garden into four quarters.

After the Arab invasions of the seventh century, the traditional design of the Persian garden was used in the Islamic garden. Persian gardens after that time were traditionally enclosed by walls and were designed to represent paradise. In the Charbagh, four water canals typically carry water into a central pool or fountain, interpreted as the four rivers in paradise, filled with milk, honey, wine and water.

The general theme of a traditional Islamic garden is water and shade, not surprisingly since Islam came from, and generally spread, in a hot and arid climate. Unlike English gardens, which are often designed for walking, Islamic gardens are intended for rest and contemplation and usually include places for sitting. ‘The Wagner Carpet’ too offers a garden that delights the eye and soothes the mind.

“Eternal Springtime: A Persian Garden Carpet” is being displayed at the Islamic galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York from July 10 to October 7, 2018

Published in Dawn, EOS, July 29th, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.