Viewers who frequent galleries are familiar with the caption ‘Untitled’ — they know that the artist who has produced this work has chosen not to name it and prefers that the painting speak for itself. Yet, titles are in a way the first and the most accessible tool in the encounter with an artwork. The name of a piece serves as an introduction to the ideas and themes that the artist is trying to communicate and helps the audience form their interpretation.

However, despite the benefits that a good, descriptive name can bring, many artists throughout history have opted out, choosing instead to title their artwork ‘Untitled.’ The reasons behind this are as varied as the works themselves but generally many artists enjoy the idea of offering something to the world on their own terms without any additional context or placement within time or space. Nevertheless, ‘Untitled’ is still a title and leaves one wondering whether the concerned art is what the artist says is art or what the viewer thinks it is. This element of mystery prompts multiple readings.

There are many reasons for not titling artworks, and many philosophies about titling. While some artists think of phrases out of thin air, others struggle with titles. Most artists do not title for a very simple reason: titles come from the intellect and that is not where most art comes from. Many abstract artists do not title their work as they prefer the work to be viewed completely objectively. Some artists want to convey a distinct meaning, others want to confuse, obfuscate or evoke irony. J.M.W. Turner is an example of an artist who used ironic, complex titles — for instance, ‘The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838.’ Tracking untitled artworks online is difficult and they create bookkeeping problems for galleries keeping records of what has been sold to whom. A good title can help sell the artwork and become a part of the buyer’s narrative; conversely, a bad title can hamper sales.

How far does the title of a painting weigh in on understanding the artwork itself?

Surprisingly, titling artworks is a modern phenomenon. The history of the picture title spans the last 300 years. In earlier periods, when works of art were produced for the elite, there was not much need for titles: the patron and artist typically negotiated a picture’s subject, and the eventual owners, more or less, knew what they would be seeing.

Works of art that remained site-specific and visible largely to a local population also didn’t require titles. Think of an altar in a local church or a fresco in a princely palace. But, when images begin to circulate widely, the art market grew and public viewing spaces, such as the 18th century salons or modern museums, were established. Art criticism evolved and people began to connect images with titles and descriptions. At the same time, new technological developments, from popular prints to computer images, allowed for inexpensive reproductions to reach a wider audience.

Dealers, writers, poets and curators were the most common source of titles. Edouard Manet painted his most famous work in 1863 but it remained unnamed. The poet and critic Charles Baudelaire referred to it the following year as ‘Nude with a Black Cat’ but it was Manet’s friend Zacharie Astruc, a critic and fellow painter, who named the painting ‘Olympia’, which Manet used when he submitted the work to the 1865 salon.

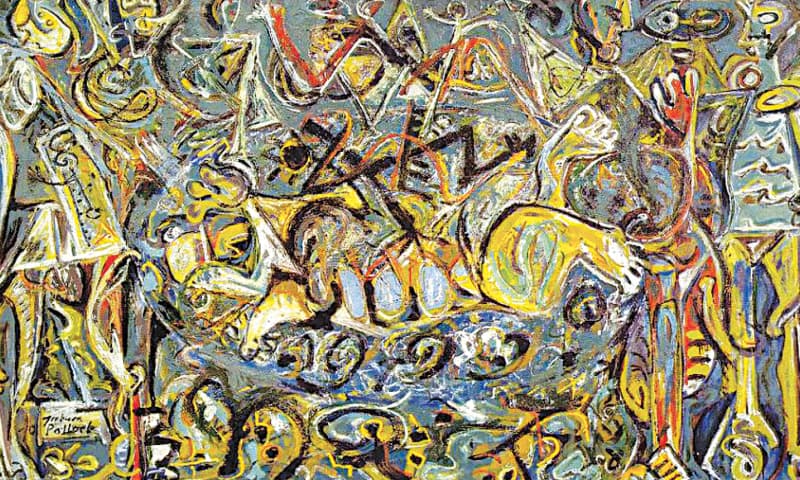

Even modern pictures often derive their titles from middlemen. Jackson Pollock’s ‘Pasiphaë’ (1943) appears to have been named after the mythical queen who cuckolded King Minos and gave birth to the Minotaur, and some distinguished commentators interpreted it accordingly. But Pollock had actually intended to title his painting ‘Moby Dick’: it was a museum curator who came up with ‘Pasiphaë.’ “Who the hell is Pasiphaë?” the artist is reported to have inquired.

Yet even when modern scholars have good reason to question a traditional title, both that title and the interpretation it implies can be almost impossible to change. In the 19th century, commentators realised that Rembrandt’s ‘The Night Watch’ neither depicted a watch nor took place at night. But the painting continues to be recognised by that name.

Giving a title to a work of art is relative to the artist’s preference and viewer /buyer perception but historian E.H. Gombrich points out that, “The chance of a correct reading of the image is governed by three variables: the code, the caption and the context. Jointly the media of word and image increase the probability of a correct reconstruction.”

Published in Dawn, EOS, July 1st, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.