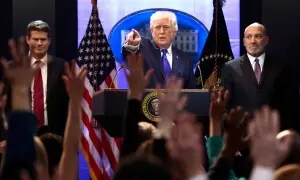

THE obscenely opulent reception arranged in Donald Trump’s honour, with Arab autocrats lining up to pay homage to the American president, forgetting his inflammatory anti-Muslim rhetoric and his likening of the Saudi royal family to ‘slaveholders’ in the past, did not come as a surprise. Nor did the US leader’s softened tenor as he addressed the so-called Arab-Islamic-American Summit in Riyadh last week.

Indeed, there was no mention in Trump’s speech of ‘radical Islamic terrorism’, a term he often used during his election campaign. But what excited the Saudi and Gulf kings gathered at the forum was Trump’s tirade against Iran which he declared was the centre of terrorism and extremism. In the midst of their insecurity, these remarks struck a chord. In the new American president, the Arab despots found a trusted ally and protector that they had missed in his predecessor.

What was supposed to be an alliance against terrorism and extremism has virtually turned into an anti-Iran coalition further widening the regional geopolitical divide. By citing Tehran as the centre of gravity of terrorism, the American president has encouraged sectarian warfare among the Muslim-dominated countries thus diverting attention from the actual sources of extremism plaguing the region and beyond.

What was supposed to be an alliance against terrorism has virtually turned into an anti-Iran coalition.

Surely Tehran too is to be blamed for the ongoing proxy wars in the Middle East along sectarian lines. It is actively involved in the Syrian and Iraqi civil wars. But targeting the country as the bastion of terrorism and extremism is extremely dangerous. Ironically, Iran and the US forces have been collaborating in fighting the militant Islamic State (IS) group in Iraq, while Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries are supporting some extremist Sunni militant groups fighting in Syria.

This approach of containing Iran is bound to further inflame the situation in the Middle East that will have spillover effects in other Muslim countries, especially Pakistan. Interestingly, it’s all happening as the Iranian people re-elected Hassan Rouhani, a moderate, as their president who was also responsible for reaching a landmark nuclear deal with the United States and other nuclear states.

Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states were strongly opposed to the treaty and called for tougher US action against Tehran. The Iran nuclear deal was also the reason for the widening gap between Riyadh and Washington under the Obama administration. The Saudis were extremely worried by the possibility of a US-Iran rapprochement. But those fears lessened after the election of Trump who advocated a tougher stance against Iran and also vowed to scrap the nuclear deal — though it may not be possible considering there are five other signatories.

Hence the grand reception for the new US president when he chose the kingdom as the first destination of his maiden foreign visit as president. The Saudis have also obliged him by signing a multibillion-dollar arms deal and promising to invest billions more in infrastructure development in the US.

Those business deals with the prospect of generating thousands of new jobs in the US have certainly thrilled Trump. The development has also marked the return of the US to its traditional Saudi-centred Middle East policy.

However, given the Middle East civil war and the rise of more dangerous global terrorist groups like IS, a partisan American policy could complicate the situation, further destabilising the region.

It will certainly encourage Saudi Arabia to adopt a militarily more aggressive approach in Yemen and other troubled spots. It may also lead to an escalation in the Iranian proxy war in the region. There is some indication of a realignment of forces in the Middle East with Israel providing implicit support to the Saudi-led coalition of the Gulf countries. What is most worrisome is that any escalation may provide greater space to jihadi groups like IS and Al Qaeda.

This situation raises serious questions about Pakistan’s involvement in the Saudi-led alliance, sometimes described as the ‘Arab Nato’, with its clear anti-Iran bias and apparently divisive agenda. Whatever ambiguity there was about the aims and objectives of the 41-member coalition must be clear by now after the speech at the summit by Saudi King Salman Abdul Aziz who did not mince his words, describing Iran as the main enemy. A major question is whether we also agree with the Saudi agenda.

Frankly speaking, it didn’t matter that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was not granted a private meeting with Trump or that he was not given an opportunity to address the summit. The main question is whether such a divisive Islamic alliance (in sectarian terms) in any way serves our national security and foreign policy interests. It certainly does not.

It was so obvious from the outset that the alliance would not work when its formation was announced unilaterally by the Saudi crown prince in the midst of the kingdom’s military intervention in Yemen. It was a major mistake to commit ourselves to the coalition without having a clear idea about its objectives. Even worse was allowing retired Gen Raheel Sharif to head a phantom Islamic army.

With a former army chief in the top position, we cannot pretend that Pakistan is not an active partner in the military alliance. The government’s decision was in complete violation of the parliament’s resolution to not get involved in the Middle East civil war.

It is also a failure of our foreign policy as we have been unable to clarify our position on the anti-Iran stance at the Riyadh summit. Indeed, it will now be much more difficult for us to extricate ourselves from what is rightly described as a ‘Sunni’ coalition without further antagonising Riyadh. But staying in an alliance which gets us involved in an intra-sectarian conflict will be extremely dangerous for the country.

One had hoped that an inclusive alliance of Muslim-majority nations would help bridge the sectarian divide and bring an end to the civil war in the Middle East. But the so-called Arab-Islamic-American Summit has dashed that hope and only added to the prevailing instability.

The writer is an author and journalist.

Twitter: @hidhussain

Published in Dawn, May 24th, 2017