When it comes to talking about menstruation, women get creative — code names are de rigueur.

The period is a “friend visiting”, “Aunt Flo”, “my time of the month” and any other mixture of bizarre titles. Yet, beneath all these code names is the underlying language of shame and disgust; of attempts to disguise a natural bodily function most women experience every month.

Shame is fundamental to the 'family-friendly' terms for menstruation.

It is the admission that you are impure and your body cannot be permitted into certain spaces. It is a silent suffering; an acceptance that this is one experience we are expected to keep locked inside the harem, lest we offend the other half of the population.

Also read: On paper bags, purity and periods

So when a group of students in Lahore decided to tackle this shame head on, they were accused of elitism, of manufacturing oppression by — you guessed it — concerned, liberal-leaning men.

A group of women (and men) installed menstrual pads on the Beaconhouse National University campus with labels like “This blood is not dirty”, “It’s something so natural” and “Why should I be embarrassed?”

The idea behind the protest was to make people aware of how women are often shamed for going through a natural, biological process.

They were roundly berated for the public display, accused of spreading dirty images and told "it really was not a big deal".

Also read: Dear Pakistani men, here's how you talk about periods

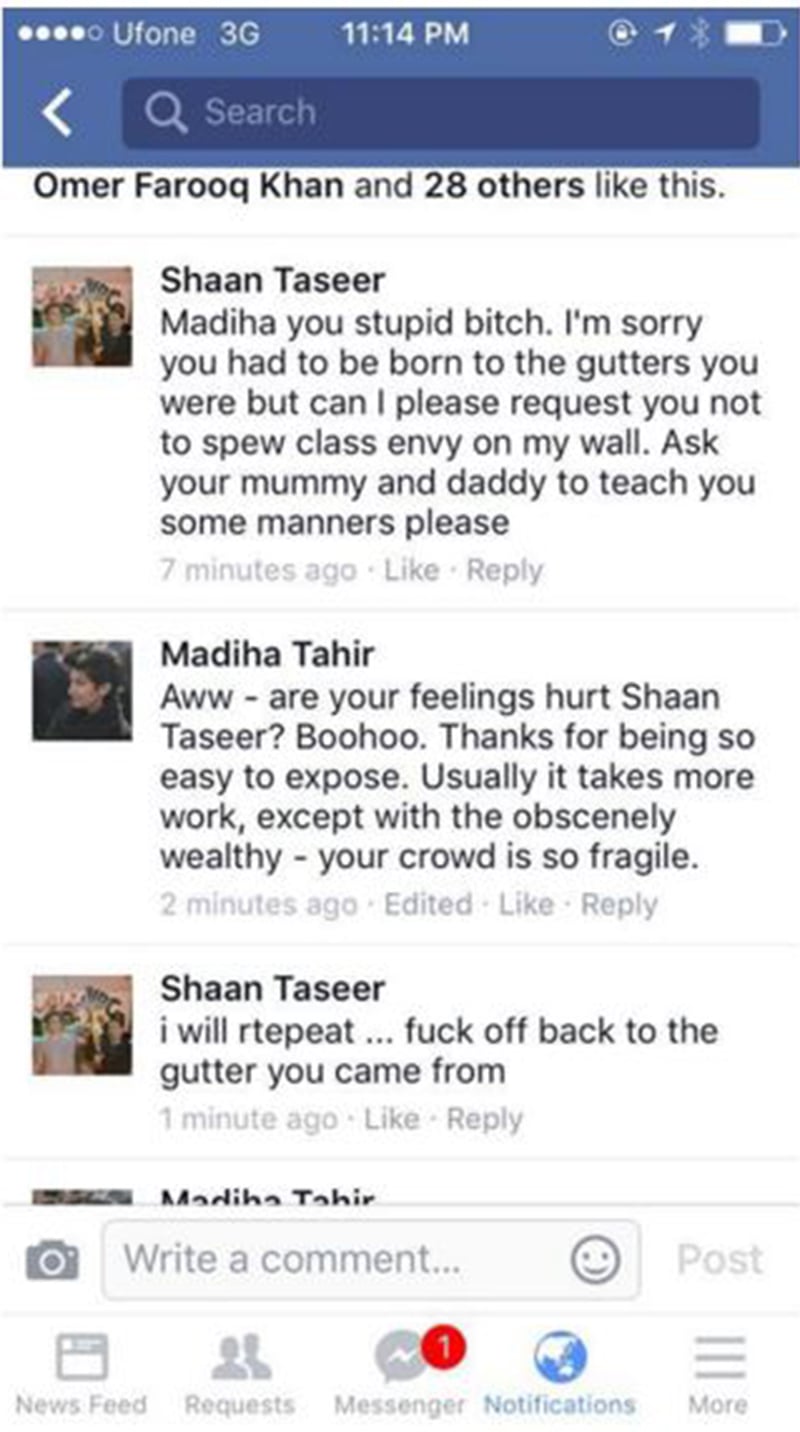

Most recently, the students' protest served as the unlikely catalyst for a war of words between Shaan Taseer and journalist Madiha Tahir. The same Taseer who has recently been in the public eye for speaking out against Lal Masjid cleric Abdul Aziz.

In his post, Shaan Taseer accused the BNU students of being Pakistan's 'bourgeois' lot, apathetic to the plight of the average Pakistani woman who he firmly believes remains unaffected by their protest.

After he disdainfully labeled the BNU protest a result of a privileged classes' frivolous problem, he himself resorted to offensive class-based insults at Tahir — a dramatic contrast from what he was initially championing.

Why should the social class of the BNU students be a factor to undermine the protest?

The very fact that the BNU protest triggered such a reaction just validates the disregard that members of the educated elite have for the struggles of half of the population in Pakistan — that they are simply oblivious to the shame that underlies menstruation for all women in this country.

Patriarchy is a pretty interesting phenomenon, like a virus, it informs everyone’s views, without regard for their class, educational background or gender.

It is not surprising then how it has infected even the supposedly liberal, supposedly progressive, who claim to speak for the disadvantaged.

These critics, and the loudest of whom are men, are offended by an experience they know nothing about.

Yet patriarchy, a system where men have always had a space to share their views, allows them to interrupt a conversation for which they are woefully unqualified, by virtue of their gender.

Yes, the stigma surrounding menstruation impacts the most economically and geographically disadvantaged women. But without an open discussion about menstruation, whether on a university campus or in a health clinic in a village, all women in Pakistan will reap the consequences of a lack of information and debate.

Most rural Pakistani women rely on recycled cloth and rags when menstruating, and are unable to access the right health resources partially because their menstrual hygiene is not high up on the list of concerns of healthcare providers — there is also no cheap, sanitary, widely available alternative to rags.

If the students at the BNU have taken it upon themselves to expand this discussion, then ultimately, the benefits will be reaped by women from all backgrounds in Pakistan.

Also read: Five ways Pakistan degraded women

Who is providing period supplies to women leading displaced lives in refugee camps and slums?

Who is talking to an impressionable girl experiencing her first period, who doesn’t want to go to school that day?

These questions are part of the discussion and why all women need to be framing this discussion in the first place.

If some men are squeamish about the conversation on menstruation, then for once, they should stay silent and let the women take the stage.

Maybe then, we won’t need to use code names for their convenience.