Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan’s declaration that his government will now direct its energies to countering sectarianism can only be viewed as a positive development, though it will take a lot to pacify sceptics who continue to raise concerns about the slip between cup and lip.

The minister declared zero tolerance for those terming others as ‘infidels’, questioning their faith and fuelling sectarian fires in the country, already polarised along a number of lines. Nisar’s statement was significant inasmuch as it followed two rounds of consultations with the leaders of the umbrella organisation representing the Madaris (or religious schools) all over Pakistan.

Most significantly the second round of consultations chaired by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was also attended by the Chief of Army Staff General Raheel Sharif and the Director General (DG) of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

If the interior minister’s words can be read as representing the civil-military consensus on the issue, there would be no sweeter music to many ears in Pakistan.

Nonetheless, the rollout of practical measures will be keenly awaited, because though the roots of sectarian intolerance in Pakistan in terms of a major incident can be traced back to the early 1960s, it nowhere near represented the constant persecution of sectarian and religious minorities which started in the 1980s and continues unabated to this day.

Two things happened towards the end of the previous decade, in 1979 to be specific. The march of the Soviet army into Afghanistan, and the Iranian revolution which saw to power a Shia theocratic regime would have profound impact on Pakistan. Both these events created a tidal wave of change, and a nasty one at that, as hundreds of millions of dollars started to flow into Pakistan to indoctrinate thousands of impoverished people into becoming virulent militants.

The primary aim of the western powers led by the United States was to counter Soviet influence in the region by trying to force out the Red Army from Afghanistan. Some of the West’s Gulf allies led by Saudia Arabia shared this goal but also wanted to bolster anti-Shia militant forces to nullify any influence Iran acquired over Pakistani Shias, many of whom saw Imam Khomeini as a credible religious leader.

The Shia protest over Gen Ziaul Haq’s rollout of Islamic laws, including forced deduction of Zakat, which saw thousands gathered in Islamabad in the summer of 1980, shook the regime. While Zia amended the law and made Shias exempt from this forced levy and allowed them to pay, collect and distribute Zakat as per their own ‘fiqh’, he never forgave them. And the result is there for all to see.

One particular Muslim school of thought, regardless of how small the number of Pakistanis who adhere to it, was patronised by the State to a point where its influence (just count the number of mosques and madaris controlled by it) outstripped others which together may have represented some 80 per cent or more of Pakistan. This particular school of thought provided the cannon fodder for the anti-Soviet military campaign.

Then, realising the efficacy of such ‘non-state’ actors, the military establishment started to further develop and deploy these ‘assets’ to its covert wars in Indian-occupied Kashmir and in other areas of ‘strategic’ interest.

Whereas in the past, such as in the genesis of sectarian violence in the country, for example in the southern Punjab town of Jhang, sectarianism may have been rooted in the tussle between the haves and the have-nots, what fuels it today is toxic ideology and nothing more, which explains its scary intensity.

This backdrop leads one to believe that the challenge is enormous and will require an iron will to meet it with any level of success.

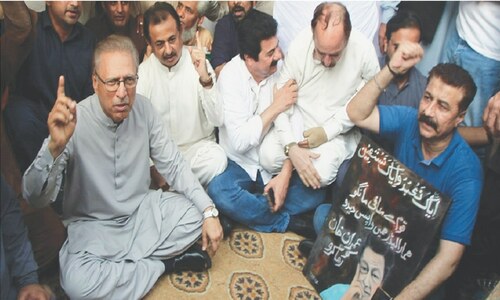

For a start, let’s see if key government ministers stop publicly fraternising with sectarian leaders who routinely make hate speeches and lead frenzied slogans of ‘Kafir’ against other sects.

Equally, the military will have to demonstrate that anyone whose hand causes murder and mayhem in the country and violently drives wedges in society is not and can never be an ‘asset’ and needs to be brought before the law.

Once we have such demonstrable evidence, the reservations about welcoming Nisar Ali Khan’s statement will melt away and be replaced with relief and joy.