However, because Pakistan has historically refused to act against certain militant groups — such as the Haqqani network — Americans fear that their interests do not coincide with that of Pakistan. Therefore, from the American perspective, the relationship is one of mistrust and unmet expectations. In his book Magnificent Delusions, Pakistan’s former ambassador to Washington, Husain Haqqani, writes that America sees Pakistan as making and breaking promises since the time of the Soviet war.

While tracing the historical trajectory of a relationship based on mutual incomprehension from 1947 onwards, Haqqani clearly states the position of both countries: Pakistan sees America as an unreliable ally with a regional agenda as well as a military warehouse for the procurement of defence equipment and a guarantee of economic security. And while America over decades might have perceived Pakistan as an important geopolitical partner in times of war (the Cold War, 1954-72; the Soviet war, 1979-89 and the ‘war against terrorism,’ 2001-present) and as an “ally in creating an opening for US ties with China,” it also sees it as an “irritant” obsessed with India; and a country where the “cancer of terrorism” is so acute that the Obama government decided to “target, train and transfer in Afghanistan so the cancer doesn’t spread there.” Haqqani quotes a New York Times report where Obama stated that “it did not matter how many troops were sent to Afghanistan if Pakistan remained a haven [for militancy].”

From the Pakistani perspective, it supported US counterterrorism initiatives and policies after 9/11 — targeting Al Qaeda and other linked regional militant organisations — in exchange for aid. For its part, Pakistan believes that the US will abandon the region (Obama’s initial announcement of a withdrawal timeline after which combat troops will not remain in Afghanistan has been interpreted as lack of commitment) as it has in the past. Thus it feels the need to safeguard its strategic interests and counter Indian influence in Afghanistan. This is also why America’s support for Pakistan becomes all the more urgent.

Perceptions about the other have fuelled greater instability in relations between the two countries. Successive governments have either enjoyed a cordial or less-than-cordial personal rapport among counterparts within the military and civilian governments who have often misunderstood each other’s limitations. Even so, some smooth sailing in this relationship can be attributed to close personal associations between leaders from both countries — Ayub and the Eisenhower government; Richard Nixon and Yahya; Musharraf and George Bush — but that cannot (and has not) alter national priorities. Haqqani writes that Americans have always questioned what they get from Pakistan in return for aid (and for often turning a blind eye to human rights abuses and transgressions, such as nuclear proliferation and export of terrorism) and whether Pakistan can be trusted (the raid against Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad is an example of this mistrust), whereas Pakistan wants more aid.

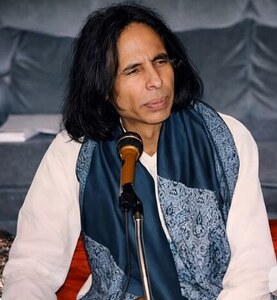

As Pakistan’s ambassador to the US from 2008 to 2011 (at the time when Bin Laden was killed in the Abbottabad raid), Haqqani was privy to the inner machinations of the army and the civilian government and had to defend his government against various accusations. He has also been a long-time critic of the military establishment and its alleged role in nurturing militant proxies. The author of a previous book, Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military (2005), which focuses on the links between Islamic extremism and the military, Haqqani’s viewpoint is not favoured within the Pakistani establishment. His tenure as ambassador ended when he resigned and left the country after the ‘Memogate’ incident in 2011, when he was accused of seeking US help to rein in the Pakistani military.

Haqqani refers to Ziaul Haq as “a most superb and patriotic liar,” for instance, for convincing the Americans in the ’80s that Pakistan would not persist with its nuclear programme or test nuclear weapons. Haqqani is quick to dissect how Zia took the opportunity to play hide-and-seek with the US (“in pursuit of American aid, he told The New York Times that ‘Pakistan was not making a bomb’”), astutely pointing to the changing dynamics in the relationship between both countries at that point. Anti-communist hardliners might have been attracted to Zia’s rhetoric with Carter endorsing the CIA assistance programme for Afghan resistance being routed through Pakistan — Zia also got the Saudis on board his Afghan project — but the aftershocks of this jihadi war project remained Zia’s legacy in the region and the ‘war on terror’.

It is interesting to be reminded how little this relationship has changed when it comes to Pakistani leaders clamouring for aid and the American misconception that they can demand prerequisites to assistance. The post-Partition years witnessed persistency on the part of Pakistani leaders requesting assistance with building an army though America was not eager to push aside India while courting Pakistan. And America made that clear to Pakistan. Even then it was believed that with India and Pakistan “it was difficult to help one without making an enemy of the other.”

But the CIA was wrong to believe that Pakistan would align its policies with the West and be willing to provide troops to secure the Middle East in return for US pledges to secure its borders against India, writes Haqqani. The Americans had also believed that bases in Pakistan would be offered in exchange for aid. “In 1947-48 Pakistan had yet to do anything for America, yet it still expected huge inflows of US cash, commodities, and arms,” Haqqani writes. It requested a $2 billion loan; the US responded with 0.5 per cent of that amount, $10 million.

Historically, Pakistan has never rejected American aid outright — whether for military or civilian purposes — and it was no different during the Cold War (and later the Soviet war) as lucrative assistance came Pakistan’s way. In return, Pakistan assisted in spy operations against the Soviets and later during the Soviet war, America was pleased as Russia “lost more men and equipment than they had in any military engagement since World War II.” Partial credit for this goes to the American provided Stinger surface-to-air missiles used by the ‘mujahideen’. Not only had Pakistan given two-thirds of its resources provided by the CIA to Islamist groups by the late 1980s (decades later, former US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton had acknowledged that America had financially assisted the ‘mujahideen’) but Zia had exercised his ambition for control in Afghanistan through the installation of a ‘friendly’ government and with the help of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence.

Nothing Haqqani writes regarding the pattern of the US-Pakistan relationship is unknown. But his retelling of history reiterates that placating one another has led to greater distrust and acrimony as the relationship remains motive-driven and insincere, at best. American motives for engaging Pakistan in times of war have differed from the latter’s interest and reasons to participate. America’s military, civilian and development aid hasn’t rid the country of growing anti-Americanism or a dangerous right-wing ideology. This is especially true as the Obama administration’s ongoing drone programme generates hatred and suspicion among Pakistanis even though ground intelligence is locally provided with the tacit understanding of the Pakistani establishment.

The long-held and presumptuous perception that America needs Pakistan more than Pakistan needs America, which is what Jinnah had said when he called Pakistan the “pivot of the world” in 1947, is reflective of our country’s delusional thinking (and working), notes Haqqani. Failing to learn from past mistakes has further destroyed the trust between the two countries. In 2012, when Pakistan shut down Nato supply routes through the country, forcing the international community to find expensive alternatives to refuel the war effort in Afghanistan, a similar belief system came to the fore. After the Abbottabad raid, America was able to publicly voice its anger at Pakistan and stated that it was supporting terrorism “as part of its national strategy.” Pakistan, for its part, was unwilling to admit that anything was wrong and needed to be straightened.

Richard Holbrooke believed that America would get more out of Pakistan through engagement than bullying and isolating, and this stands true at present. As special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, Holbrooke believed trade and economic ties with regional countries would strengthen Pakistan as would assistance in the education, health, and energy sectors. Senior advisor to Holbrooke, Vali Nasr, recalls that this advice was disregarded by the Obama administration at a time when the schedule for a troop drawdown had already been chalked out. Pakistan is a failure of American policy, wrote Nasr in his book, The Dispensable Nation, in which he stated that a prudent course of action would have led to greater engagement. Managing Pakistan to re-shape the US-Pakistan relationship needs to be thought through without giving heed to the conspiracy theories and hatred that have shaped the narratives in both countries.

Haqqani’s detractors may claim he favours America’s way forward vis-à-vis Pakistan, whereas in fact he treads a careful and balanced position, holding both America and Pakistan equally responsible for their relationship of mistrust which needs acknowledgement so that expectations are lowered and divergent interests understood. America, he advises, should not expect aid to translate into leverage, and Pakistan must not pursue its military ambitions through American aid. The problem lies in identifying Pakistan’s national interest: it cannot become a regional player and leader in South Asia while supporting terrorism. Pakistan’s survival is hinged on redefining its priorities when it comes to fighting militancy and aiding economic progress.

Magnificent Delusions: Pakistan, the United States, and an Epic History of Misunderstanding

(history)

By Husain Haqqani

Public Affairs, US

ISBN 1610393171

432pp.