"Nations have been defeated politically and economically, but their intellectuals, working under the influence of civilisation, literature and culture, not only transformed the political and economic defeat into victory but also overcame hostile forces."

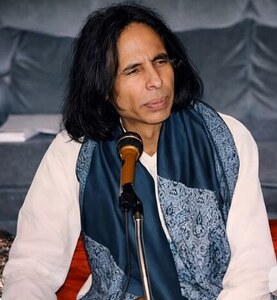

Believing in his own frame of reference, Ghulam Murtaza Syed, popularly known as G.M. Syed, devoted his life to the formulation of a distinct national identity for Sindh, both on intellectual and political fronts. The goal of his entire life focused on this single cause: the political autonomy and prosperity of his ill-fated land, Sindh, and her inhabitants. Syed offered mysticism as the ideology to achieve this objective. He was among the last of thinkers and politicians who tried to change the course of history through their politics based on ideologies.

Nonetheless, in clear contrast to the official discourse of Pakistani nationalism based on Muslim identity, Syed was a strenuous supporter of Sindhi nationalism culturally rooted in mysticism. He was also a severe critic of state ideology and the two-nation theory. Consequently, he was labeled and pronounced anti-state and anti-Islam by the pro-state intelligentsia. He remained a controversial figure in the politics of Pakistan and his intellectual work redefining the concept of religious identity and cultural nationalism in Sindh was often misunderstood.

However, when it came to conviction and commitment to his cause, Syed was regarded as a person of indisputable merit by all the ranks of the establishment. It is unfortunate that he was never offered a chance to defend the charges against him in any court of law, despite the fact that he paid a very high cost in the form of almost 33 years of imprisonment, sometimes even in solitary confinement. He died in police custody at Jinnah Hospital at the age of 91.

It is a misfortune that this giant literary figure was always overshadowed by his "controversial" political personality. The author of more than 60 books, Syed, as remembered by Dutch scholar Oskar Verkaaik, "was in many ways a remarkably productive, original, and largely autodidact intellectual, creating his own personal interpretation of Islam out of a range of intellectual influences such as 19th-century Islamic reform, Darwinian evolution theory, theosophy, 18th century Sindhi poetry, Marxism, classical Sufism, German idealism, and probably more." Beside many books and articles on political ideology, Syed also wrote on culture, history, politics, religion and theosophy.

In his book Religion and Reality, Syed offers a detailed account of Sufism and its comparative study. He explores the notion of mysticism interwoven with the Sufi traditions of land, historically associated with the dispossession of private property. Syed dedicated this book to Shah Inayatullah, the great saint and mystic of Sindh, often known as Shah-i-Shaheed. He waged a war against religious prejudices and local landlords by quoting the Persian couplet:

"Gone is my head in the way of God Verily, it was a great burden for me."

These were the actual words uttered by Shah Inayat right before his death.

Shah Inayat Shaheed was called the first socialist martyr by Sibt-i-Hasan, a renowned Marxist scholar, because he died leading a peasant movement under the slogan that the land belongs to those who plough it. He was killed by a fake fatwa through a conspiracy of the landlords. Thereafter, the mullah has remained a figure of condemnation in the folk poetry of the land.

Furthermore in Religion and Reality, Syed rejects the concept of revelation and instead offers a theory of the evolution of religions where Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam and science are considered as the different stages of the evolutionary process of religion. However, he declares not science but mysticism as the final and ultimate destination of humankind's search for absolute reality.

Thus Syed constructs the cultural and political identity of Sindh on the foundations of mysticism and segregates it from religion, which is interpreted and dominated by the clergy. He defines mysticism as a code of life which consists of belief in the unity of diversities, the rejection of the domination of the clergy, the segregation of state and religion and the equality of human beings. He writes, "the collective life of humanity, passing through various stages of evolution, is advancing towards its final goal, which is the unity of thought and action." The objectives of all religions may be defined as unity, peace and the prosperity of the human race, and for this Syed believed Sindh, as the cradle of mysticism, would have to "play a particular role": "the land of Sindh has to deliver a special message of love and it has to play a particular role."

Syed was fully aware of the fact that his book could be misunderstood - that while the orthodox might label him an apostate or a communist, the progressives, inclined to materialism, might declare him a conservative Sufi mullah. The expected reaction transpired and the book was banned, but all the fuss couldn't shake the honest sharing of his intellectual endeavours and ideological beliefs.

Syed uses the ideological frame of mysticism in his political ideology of "Sindhu desh." He rejected the false notion of a nation-state based on religious identities. Instead, he established a theory that Sindhi culture, based on the unity of religions, would lead to the unity of cultures.

In his book Sindhi Culture, Syed articulates culture as the inner and outer development of the personality of an individual and a nation, a "bottomless well of expression, emotions and actions." For him, culture is an organic reality of nations nourished over centuries, passing through the evolutionary process and subsequently achieving the absolute reality of the oneness of all cultures, the synthesis of many into one, a cosmopolitan culture. He characterises Sindhi culture as rooted in the Sufi (mystic) code of life and the traditions of love, non-violence, co-existence, non-partisanship and finally, the right of self-determination.

Viewing the perspective of history held by most people, Syed not only rejects the official narratives which were largely written by court historians belonging to the ruling regimes of respective times but he reinterprets the history of Sindh and introduces Raja Dahir, Mukhdoom Bilawal, Doleh Darya Khan, Dodo Soomro and Shah Inayat as the native heroes of Sindh and the pride of the Sindhi nation. All these people were put to death in wars against invaders, and among them Makhdoom Bilawal and Shah Inayat were the martyred Sufis of Sindh who challenged the authoritarian regimes of their times. Thus Sufism in Sindh became a symbol of resistance against authoritarianism. Syed denounces the theory that Islam came through the conquest of Mohammad Bin Qasim; rather, it spread through the preachings of Sufi saints, he claims. He condemns Mohammad Bin Qasim as an invader and argues that authoritarianism of both state and religion has always been resisted by the native inhabitants of Sindh. The clergy, authoritarianism and orthodox Islamic teachings never found adherence in Sindh and the mullah has remained a figure of condemnation in Sindhi folk culture and in the poetry of Sufi poets:

"The Mullah committed suicide when he recognised the truth about Allah The Mullah's mother is deeply anxious, feeling that she is filled with poison." (Shah Latif)

Syed has also reinterpreted Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai in Paigham-i-Latif. Unlike previous interpreters who looked at Latif as a saint to be understood only through spirituality, Syed provides a comprehensive socio-political analysis of his times. In Syed's view, patriotism, freedom, prosperity of the country, deliverance from corruption, the spirit of self-sacrifice and tolerance are the highest values the poet has successfully inculcated in the people of Sindh through his verses. For Syed, Latif stands as an icon of the collective social consciousness of the nation, revealing the ethos and the deep sorrows of the people of Sindh.

Almost all of Syed's literary works offer an alternative theory to challenge the established discourse on religion, history and politics. They initiate a new and productive discourse, rendering his literary work controversial and antagonistic in the eyes of the Pakistani establishment. However, the salvation of Sindh and mysticism remains the central theme in his works.