Of the three countries that were once a single entity, Pakistan seems to have fallen way behind. With all its posturing, waving of the green flag, shouts of ‘Pakistan Zindabad’, it cannot fudge the historic numbers that blatantly tell the story of economic and political turmoil that led to neither growth nor human development. Without an excuse for its inept management, Pakistan lags behind India and Bangladesh in most indicators.

Rupee’s journey

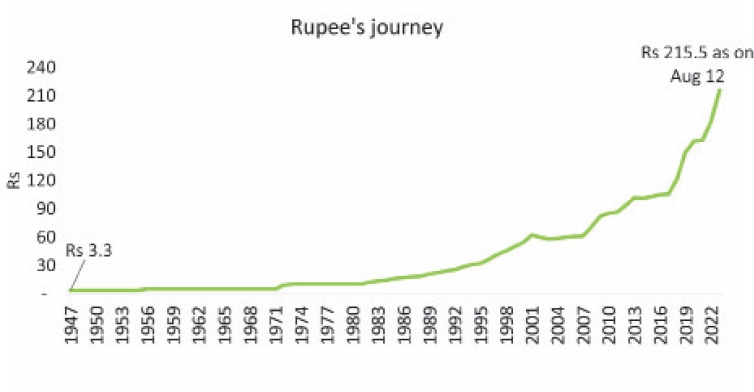

After independence, remnants of Pakistan’s colonial heritage lingered for the rupee that remained linked to the pound sterling till September 1971, according to the State Bank. Given the bungee dive that the rupee has taken of late, a time when the PKR remained constant for years seems like the golden period. It wasn’t.

In 1949, the Bank of England devalued the pound sterling relative to the rupee, leading India to follow suit. By keeping the exchange rate constant, Pakistan’s exports were expensive relative to its competitors in its main market at the time of independence: India. An archived New York Times article of August 1, 1955, states that the Pakistan Government reduced the value of the rupee by one-third in a day, bringing it down to the same rate as India in hopes of boosting exports. An effort that was too little too late.

Pakistan maintained a fixed exchange rate till 1982, converting to a managed floating system that remained in place till the International Monetary Fund put its foot down in 2018. Previously, Pakistan used to keep the dollar artificially stable by selling its reserves, hardly feasible during current times when the country floated perilously close to a default.

Averaged out, the Pakistani rupee has steadily weakened since it came into existence with the recent appreciation being an anomaly following weeks of speculation that artificially pushed up the value of the dollar.

Inflation

“In our time, we got a few anna for pocket money,” muse old grandparents while tch tching at prices. Though this is a refrain multiple generations have heard growing up, the prevailing over 20pc inflation rate will put the elderly horror of current prices to shame. Further adjustments are expected as electricity rates continue to march up, though the real inflation is hardly reflected in the ‘official’ rate quoted by World Bank data that was used to make the graph.

India and Bangladesh are no strangers to volatility of inflation rates though both countries have fared better than Pakistan in recent years. The recent 50pc hike in fuel prices in Bangladesh to trim its subsidy burden will further aggravate its 7.5pc inflation rate. At 95 to a dollar, Bangladesh’s taka is more than twice as strong as Pakistan’s rupee but the global crisis created by the Russia-Ukraine war has pushed it to approach the IMF for a bailout as well.

While the Indian rupee has received a drubbing as well, it is nowhere close to running to the IMF for a bailout. At around INR 80 for $1, its depreciation has been roughly 7pc in 2022 with the slight expectation that the worst is over. For both regional countries, a stronger local currency has helped hedge against inflation compared to Pakistan’s rupee’s free fall.

GDP growth rate

Pakistan’s story of GDP growth rate has always been of boom-and-bust cycles that have gotten steadily shorter. The economy overheats as soon as growth rates perk up, leading the government to reign it in and enter a ‘stabilisation’ phase while knocking at IMF’s door with the proverbial dollar bowl.

India and Bangladesh have not escaped the volatility that makes their GDP growth rate graph look like a death-defying roller coaster ride. Despite that, India’s GDP growth averaged 4.4pc during the 1970s and 1980s, accelerating to 5.5pc during the 1990s-early 2000s, and further to 7.1pc in the decade before the pandemic, according to a World Bank blog. Its progress has been broadly diversified, accelerating the fastest in services, followed by industry but less so in agriculture.

“Much of Bangladesh’s growth is owed to its exports which zoomed from zero in 1971 to $35.8bn in 2018 (Pakistan’s is $24.8bn). Bangladesh produces no cotton but, to the chagrin of Pakistan’s pampered textile industry, it has eaten savagely into its market share,” explains Mr Pervez Hoodbhoy in an article.

Population growth rate

“My husband refuses to use birth control measures,” laments Saima, a maid and mother of six children, not all of whom she has given birth to. “He already has four sons, one from me and three from his previous wife, yet he wants more while refusing to provide for any of them,” she laments. Her tale is similar to many others that belong to the lowest income classes and are solidly driving population growth in Pakistan. Without measures, the population may double in the next 33 years.

In the last six decades, India’s population has more than tripled. Despite bringing its population growth rate down, it gains about a million inhabitants a month and is on course to surpass China as the world’s most populous country by next year.

In contrast, Bangladesh has been more successful in bringing down its population rate. From government efforts to convince ulema to educate the masses to higher literacy rates for females, a combination of factors has led the country that was once part of Pakistan to bring down its fertility rate from 6.1 in 1980 to 2.3 in 2010.

GDP per capita

In 2021, before the rupee’s devaluation eroded what little strength the local currency had, India’s per capita income was over $1,000 more than Pakistan and Bangladesh’s was $740 more. Meaning: an average Indian or Bangladeshi was better off than a Pakistani.

At over $3tr, India is the sixth largest economy in the world with the second largest population. IMF’s projected real GDP growth rate for 2022 is 7.4pc. In the last fiscal year, it a record high of $418bn in exports.

Bangladesh’s exports were $52.08bn and its GDP last year was $416bn. It’s national income has multiplied 50 times, per capita income 25 times (higher than India’s and Pakistan’s), and food production four times, according to an article by Ishrat Hussain. To put their progress in perspective, Pakistan’s per capita income in 1990 was twice as much as Bangladesh’s but has fallen today to only seven-tenth, he says.

At a GDP of $346bn in 2021 and annual exports of $31bn, Pakistan’s numbers pale in comparison, explaining why an average Pakistani is worst off.

FDI inflows as a % of GDP

After an all-time high in 2007 at 3.67pc, Pakistan’s FDI as a percentage of GDP has drooped down. In 2007 and 2008, Pakistan attracted reasonable inflows of $5.6bn and 5.4bn respectively but the momentum could not be sustained owing to militant violence, global financial meltdown, political upheaval, and usual inconsistent economic policies, lack of rule of law and so on.

With over 44m cases and half a million deaths, India suffered a lot more than Pakistan during the pandemic. Despite that India continued to attract foreign direct investment at record levels while Covid-19 wreaked havoc in the country, amounting to $81bn in 2021-21, 10pc higher than the previous year.

The historical impetus of foreign cash has allowed India to improve its infrastructure and increased productivity and employment. It has led Pakistan’s neighbour to acquire sophisticated technology and mobilise foreign exchange reserves that can be used to stabilise its exchange rate.

Despite steady economic growth in the country over the past decade, foreign direct investment has been comparatively low in Bangladesh compared to India and Pakistan. At around 1pc, it is one of the lowest rates in Asia.

In absolute terms though, Bangladesh has fared better. The FDI stock in Pakistan fell from $41.9bn to $35.6bn in five years to 2020. Bangladesh on the other hand built its stocks from $14.5bn to $19.6bn and India from $318.3bn to $480.3bn in the same period.

According to the IMF, an increase of a dollar in capital inflows is associated with an increase in domestic investment of about 50 cents. As in the case of India during the peak pandemic period, FDI has also proved to be resilient during financial crises.

Another instance is the East Asian countries where investment was remarkably stable during the global financial crises of 1997-98. The resilience of FDI during financial crises was also evident during the Mexican crisis of 1994-95 and the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s.

Given its importance, is Pakistan an attractive destination for foreign investment in the region? To put it bluntly, the answer is, no, according to the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. The reason why is simple: Pakistan has had volatile and episodic growth since the 1950s with low rates of local investment, lags in innovation and low productivity.

The policymakers need to make strong efforts to come out of this vicious circle of low investment, low innovation and low productivity which is hardly possible when each government spends its tenure firefighting to keep the economy afloat while battling it out for the throne of power.

Military spending as a % of GDP

Defence is one indicator where Pakistan outshines both countries. With perpetual enmity against one neighbour, suffering from persistent low-key (and frequently high-key) terrorism from another neighbour, and various insurgencies within the country, the military chunk of the budget is 17.5pc. So for every Rs6 spent by the government, more than Rs1 is spent on the armed forces.

Though Pakistan spends a higher proportion of its income on defence, it is dwarfed by India whose military expenditure is $70.6bn compared to Pakistan’s $10.3bn. With fewer hassles on its border, Bangladesh’s expenditure is $4.4bn.

Source: World Bank, SBP and CEIC Data

Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, August 15th, 2022

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.