In one monochrome capture, dated 2007, from Arif Mahmood’s book Silver Linings, a devotee’s plaint lies next to a marbled portion of the saint’s tomb at the Daata Sahib shrine in Lahore. The plaint in Urdu can be read clearly.

“Assalaam Alaikum, Hazrat Daata Ali Hajveri (Rehmat Allah Aleh),” it begins formally. “My daughter’s wedding is on the 17th of the lunar month and on the 28th of the English month. I have nothing. Everything is possible with your blessings. Please ease my difficulties. Pray for my daughter and for me.”

This brief note, from an unnamed, ungendered devotee of the saint, in a few short, plain words, shines a light on why so many millions of people flock to shrines all over Pakistan and elsewhere. We have become so cynical about religion and its misuse — bombarded as we often are with news of abuse of power, of the financial scandals around shrines and their worldly caretakers, and the petty exploitation of people’s earnest sentiments for political gains — that we sometimes forget the human need for comfort, solace and hope that draws people to such places in the first place, people who — for varied reasons — often cannot find these things elsewhere.

In the last four decades, there has also been a ‘purist’ onslaught on the culture of shrines, which sees spiritual devotion to saints as something outside the pale of ‘real’ Islam, as a social phenomenon influenced by ‘pagan’ culture, something to be mocked and looked down upon. In its most extreme forms, this aversion has also resulted in actual violence against shrines and their devotees. Nothing engenders hate like a lack of understanding and empathy — the exact opposite of what the inclusive, tolerant Sufis hoped to instil.

Mahmood, one of Pakistan’s foremost photographers, refers to the ‘non-rational’, undogmatic, intercessionary role of shrines in his introduction to the book. He says, “the mediation of a saint between the disciple and God fascinated me … There was something special about witnessing emotional helplessness in finding tranquillity and bliss through the holy soul of the other.”

Arif Mahmood’s handsome book of photographs taken at Sufi shrines over 32 years is not simply an ethnographic documentation. It is also a personal spiritual journey

Silver Linings is actually a compilation of photographs, both colour and black-and-white, taken by Mahmood at various shrines across Pakistan — from Bhit Shah to Pakpattan, from Sehwan to Kasur, from Karachi to Multan and Lahore — over the span of some 32 years.

He says, “It is my life as a photographer and, maybe, my main retrospective.” The book grew out of an initial exhibition in 2010 and images from it have been included in a number of other exhibits, including at the Canvas Gallery in Karachi earlier this year.

But as you delve into this beautifully printed and produced coffee-table type book, you realise that Mahmood’s is not simply an ethnographic documentation. It is not with the dispassionate eye of the distanced photographer that Mahmood has captured these images. It is truly, as Mahmood acknowledges, a personal spiritual journey, an attempt to understand and internalise, that drives these pictures.

Mahmood points out that he had been taking photographs of shrines right from the beginning of his career as a photographer, but that his quest to understand began in earnest after the passing away in 2006 of his mother, whom he would often accompany on her many pilgrimages.

“After she passed away, my visits to these and other shrines increased,” he writes in his introduction. “I missed her and could relate to these places through her memory. It was as if I could feel her scent there.” This then connects the personal to the intellectual exploration.

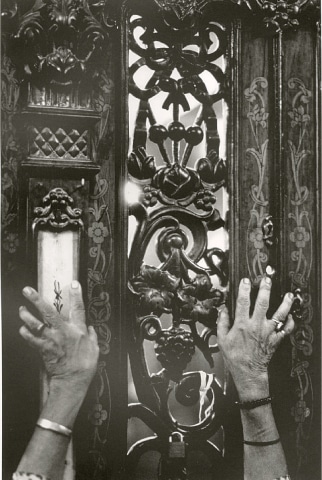

The first part of this book, a section titled ‘The Journey’, perhaps showcases this perfectly. There is the light and shadow playing off a dimly lit lamp at the Lal Das shrine in Sehwan, the glimmer of incense sticks at the Shah Jamal shrine in Lahore, the barely visible fakir at dusk at the Bodla Bahar shrine, lit only by the glow of the diya [lamp] in his hands, the blurred close-up of the moving ankle-bells of a dhammal dancer, a shehnai player straining to blow into his reed, the outstretched hand of a devotee resting on the wall of a tomb, close-ups of pillar carvings and door bolts, frescoes and mirror-work, conch-shells and silhouetted Quran readers — abstractions that convey more the atmosphere and feeling than simple visual documentation.

At the same time, these abstractive close-ups also feel like the photographer’s own rabbit-hole — you go into the minutiae not only to delve deeper, but also to lose yourself and to let yourself be overwhelmed. Recall Bulleh Shah’s admonishment to cut out extraneous distractions and get to the essence of things — the miniscule ‘nuqta’ [dot]: “Ik nukday ich gal mukdi ai.”

Other sections of the book, ‘Saints and Sinners’ and ‘Intricacies of Grace’, showcase more expansive views of shrines and crowds as well as the faces of some of the devotees, who seem to harbour many untold stories of their own journeys.

The photographs are periodically interspersed with quotes from the Holy Quran, Hadees and a durood, as well as poems and quotes by Sufi poets, presented calligraphically in Arabic, Urdu, Punjabi and Sindhi and also translated into English as an appendix at the back of the book. I noticed one small typo in one of the transcriptions, but generally much thought has gone into this book’s layout and presentation. Overall, the feeling one gets from browsing Silver Linings is that it is far more than a collection of images; it is a labour of love, in both a physical and metaphorical sense.

The first line of one of poet Munir Niazi’s couplets reads, “Mohabbat ab nahin hogi, yeh kuchh din baad mein hogi” [Love will not happen now, it will ensue a few days later]. Arif Mahmood’s process of image-making — “One sees and collects; later one finds meaning,” he had once explained to me — seems only a slight twist on the poet’s words.

The reviewer is Dawn’s Editor Magazines. He tweets @hyzaidi

Silver Linings

By Arif Mahmood

ISBN: 978-9697120437

322pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, December 5th, 2021

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.