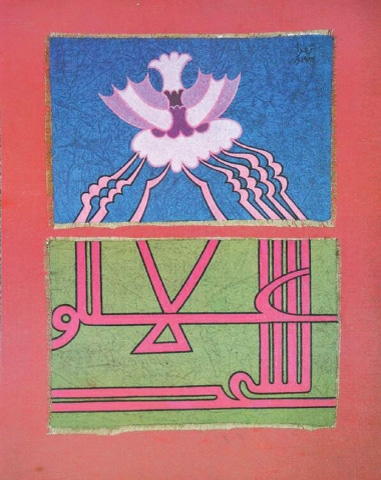

In 1984, modernist painter Anwar Jalal Shemza, who had relocated to Britain in the 1960s, was making arrangements to exhibit a new body of works, Roots in Pakistan, when he unexpectedly died of a heart attack. His wife, Mary Shemza, thought it important to press on with her late husband’s project. In 1985, she travelled to Pakistan with her three-year-old daughter, bringing with her over 100 artworks by her late husband. The memorial exhibition toured several major cities in Pakistan. Upon her return to the UK, Mary left behind five paintings, and five drawings with the Pakistan National Council of Arts (PNCA) for exhibition purposes.

At this point the narrative bifurcates and a heated controversy ensues. Mary claims that the artworks were left behind as loans, which was the understanding when the PNCA made efforts to purchase the paintings, in 1988. The offer was embarrassingly low due to a lack to funds and was duly rejected. On the contrary, the PNCA administration firmly adhered to the position that the works were in fact bequeathed to the PNCA at the culmination of the 1985 exhibition, which paid tribute to the late Shemza. The Roots series were put on display at the National Gallery of Pakistan, Islamabad, as part of the permanent collection.

“It has been a grave injustice to be without the works for so long,” comments Mary, who has pursued the return of these artworks through both personal and diplomatic channels. “I have been requesting the return of these works for the past 30 years, supported by several legal documents. It has been far from easy for me as I do not live in Pakistan. On some occasions, my emails have not even been acknowledged, even when I have backed them up with registered air mail letters.” In 2017, she engaged the late advocate Asma Jahangir to serve notice to the PNCA and commence legal proceedings if restitution was not made.

Earlier this year, the newly appointed Director General of the PNCA, Dr Fouzia Saeed, convened a verification committee to again assess the status of the Shemza artworks. The committee presented its report to the PNCA board members in a meeting in August. Based on the report’s findings, it was affirmed that the artworks were indeed on loan and efforts must be made to rectify the long-standing negligence and forceful detainment of the works. The Roots series were finally handed over to Mary’s representative (her niece based in Lahore) in a small ceremony earlier this month, and are now on their way to the UK.

Conflicting narratives around the return of 10 Shemza paintings reveal a saga of incompetence and lack of professionalism

This unexpected reversal has undermined the decades-long stance of the PNCA administration, and has elicited a heated response from some members of the arts community. Their viewpoint is that the Shemza artworks are a national treasure and returning them in such haste puts a big question mark on the impartiality of the verification committee’s report (June 2020), and the legitimacy of the ceremony of return (September 2020).

The opposition is led by the chairman of National Artists Association of Pakistan (NAAP), Ijaz-ul-Hassan who, until 2019, also served on the PNCA board. In a letter addressed to the Prime Minister, Hassan has been vociferous in claiming that the Shemza exhibition of 1985 was in fact organised “at the urgent initiative of National Artists Association of Pakistan (NAAP) to pay him tributes following his demise. Following, completion ... 10 paintings were selected by Shemza’s wife and gifted, and not loaned, to the National Art Gallery in order to ensure that her late husband’s creative art work remains on permanent display as a prominent Pakistani artist.”

The letter raised further concerns that the recent return of the artworks has set a dangerous precedent “opening the floodgates to further depletion of national art treasures” through similar restitution claims in the future.

The letter also brings to attention an FIA investigation of 2016, according to which 137 paintings by old masters were missing from the archives of the PNCA, including rare and highly valuable works by Ustad Allah Ditta and Ustad Bashratullah. Thus far, there has been no serious investigation to recover these missing works.

Several former director generals and PNCA executives also categorically oppose the return of the Shemza artworks, asserting in recent press statements that donated or gifted artworks become property of the state and the process cannot be reversed. It is also being implied that Mary is only aggressively pursuing the matter of late, now that Shemza’s star has markedly ascended and his works fetch an attractive price in international auctions.

It is true that Shemza’s stature and relevance as a modernist in the Pakistani diaspora has become prominent in the last decade or so, primarily due to the efforts of the London-based gallery, Green Cardamom. The gallery team has worked towards creating scholarship and renewed interest in Shemza’s art practice — an effort fully supported and facilitated by his wife. As a result, Shemza is today in major reputable collections in the UK, including Tate Britain and the British Museum.

Establishing the veracity of a narrative out of the two conflicting ones that are circulating these days is beyond the scope or intent of this article. However, there are some fundamental questions that need serious consideration — does the PNCA have documentary evidence that the 10 Shemzas are a gift to the Pakistani public from the late artist’s wife, dated 1985? If they were gifted, why then were offers made by the PNCA to purchase these paintings? Have the artworks ‘officially’ been registered in the PNCA permanent collection ledger, and, if so, on what grounds? Why has the apparent gap in provenance been overlooked for over three decades, despite continuous requests for return by Mary Shemza? Could there be similar gaps in provenance for other artworks in the PNCA, potentially exposing them to future claims?

Controversy aside, this incident should be considered a wake-up call. It has made glaringly visible the systemic lethargy and lack of professionalism at the PNCA, an organisation whose history is riddled with scandals and charges of misconduct. The National Accountability Bureau, which is being requested to look into this curious case of the 10 Shemzas, can perhaps solve this intrigue with a rather simple clue: provenance.

Published in Dawn, EOS, October 4th, 2020

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.