MORE than four decades after he took this country hostage, Gen Ziaul Haq’s death anniversary triggers a ritualistic lament about the generations born or brought up under his dark, repressive regime. Less familiar but growing steadily in recent years is the counterargument that casts him as a mujahid and as a leader with guts and vision.

The insinuations about his greatness, integrity and faith in his ideals was always there — spread rather thin in the proud accounts of Afghan war veterans, the earnest-sounding sworn Z.A. Bhutto enemies and the versions of many who had gained personally during his rule. In more recent times, the appreciation of his person has increasingly appeared in the mainstream.

Read: The man to answer for a lot that went wrong with Pakistan

The pious Zia image is rising slowly as his biggest rival ZAB suffers proportionally because of a less emotional, less respectable dealing with his legend in public. Just as until five years ago people felt uneasy about making any light comments about the PPP slogans regarding its ever-living leaders, it was rather rare for individuals to speak up in favour of Zia in a crowded room filled with strangers. That has changed. Now you have WhatsApp groups in which members hail Zia as a shaheed and a ruler who was brave enough to create examples even if it required him to hang a few.

These admirers who have come into the open are pretty much ‘Zia’s children’ to use a favourite term to describe those who came under his influence from an early age and could never shrug off the effects. Only they are truer representatives of his methods. They are his heirs.

There had been signs of a revival and return that we chose to ignore, as we celebrated a victory against a general that never was.

One doesn’t know if Nadra rules would allow such a preposterous request but it would be interesting to find out how many Pakistani parents named their offspring, born after July 5, 1977, after Zia. I guess it would be somewhat of a revelation for many of my friends who it seems have been nursing guarded aloofness if not outright contempt for everything associated with an individual with despicable qualities for 43 long years.

Two lakh, seventy-nine thousand, four hundred and thirty-three… suppose you were to be confronted by this many statements of defiance by Pakistanis who didn’t share your hatred for the man and the name and your disapproval for the legacy which, to our collective discomfort, is far too widespread to be summarily dismissed from the Pakistani memory slate. The discovery could be as devastating as the late realisation by the naive that a return to representative rule in itself was not the panacea for all the ‘Ziaul Haqqis’ that we had been subjected to.

We did ask a friendly Nadra official in confidence, and the gentleman graciously offered the three namesakes of the infamous dictator that he had in his family for any small errand that we wanted to assign them. Apparently, all three belonged to the post Z.A. Bhutto generation, as do so many others who share the same name.

My estimate of the local trajectory, influenced by the readings of some pro-Zia veteran journalists, tells me that they are less likely to get into an identity crisis or other controversies for bearing too heavy a label than a Qazzafi Malik or an Osama bin Ashar whose inspiration has since been seriously discredited.

Then why blame veteran journalist and old Zia loyalist Mujibur Rehman Shami Sahib for having written a column eulogising the man born of an electoral fraud? The column was well on its way. It was written and ready, and if there was to be any dispute, it had to be over the timing. It is moot if 32 years after his death is sufficient time for Zia to make a resounding comeback into Pakistani politics.

You and I may say that the resistance to his rule has faded too quickly whereas given all the cynicism that we have managed to generate around ourselves, the more popular view is that the general had never left the decision-makers’ post he had set up for himself in the heart of the country’s power base. This is manifest in the Zia-ian route a government appears to take in an attempt to solve serious issues such as the curriculum — even when that government may consist of ministers drawn from the cabinet of a subsequent military ruler with a liberal tag.

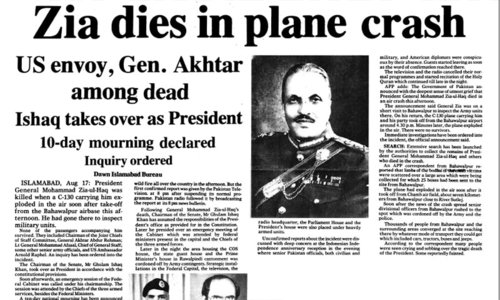

There had been signs of a revival and return that we chose to ignore, as we celebrated a victory against a general that never was. In recent years, a huge number have been found taking their contempt of the cruel usurper to a level where they observe a mock mango day on Aug 17. The gesture, in a jesting vein, commemorates those who are believed to this day to have placed a bomb inside mango cases on board the plane carrying the unwanted dictator and some others on Aug 17, 1988. Could it be that our failure to effectively put a legacy to rest is best captured by the ambiguity which surrounds the departure of the founder of that legacy, and by most progressive accounts, the individual who caused us the gravest harm?

We were denied, or couldn’t secure, the high we get from defeating an oppressor, unlike the situation in other countries where dictators are toppled by the display of people’s power in the town square. Someone did it for us. We do not know who, and it was as if we have since been waiting for that divine hand to intervene again and again.

The hidden element is most conspicuous in all commentaries on Pakistani politics, like those that tell us that though the course is unknown, the outcome is certain. We hear that such and such person — a prime minister, chief minister, or mere cabinet member — is soon going to lose their job. How he is going to be stripped off is irrelevant since you never know in this country what innovative ways may be found for an ouster that is most desired and that has been agreed upon by you never know who.

Like in life, in death, too, Ziaul Haq ensured that he frustrated the Pakistanis who preferred to pull him down.

The writer is Dawn’s resident editor in Lahore.

Published in Dawn, August 21st, 2020