Najm Hosain Syed is a most prolific poet, writer and intellectual who has contributed tirelessly to literature in the native language of Punjab. Although he has been actively writing for more than half a century and, despite having a huge number of books to his credit — 32 collections of poetry, 14 books of non-fiction and 10 plays — it is surprising that one does not see much about his works in the mainstream media. Najm seems to be standing out of the mainstream yet influencing the language and literature silently, watching the happenings around him and writing poems incessantly. Last year saw him come out with three books, this year two more have appeared. However, the sheer number of his publications should not give the impression that his is a money-churning enterprise as each book costs only Rs 30 — merely a token price in the current times.

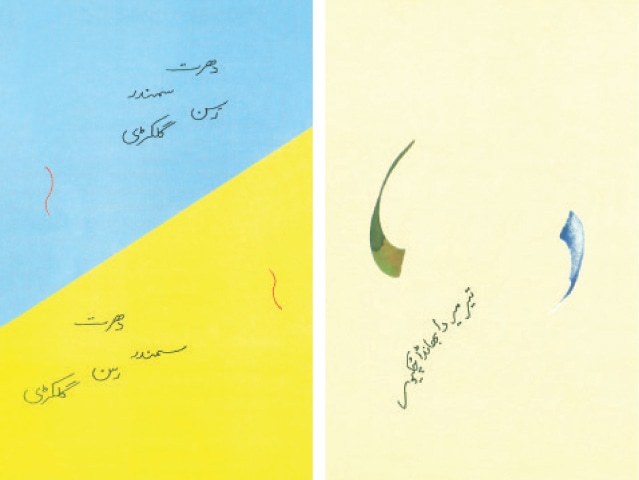

The two books that were released this year are Dharat Samandar Rasan Galakdi [Land and Sea in Embrace] and Taer Maer Da Bhanda Chukaiway [Doing Away with Yours and Mine]. For Najm, the surroundings of poets and the times they live in are of prime importance as poets react to time and space through their work and draw inspiration and imagery from them. “Why the poet draws his imagery from his immediate, everyday environment is because the environment can hold his attention and he can remain alive to it,” he writes in Recurrent Patterns in Punjabi Poetry, a book of his English articles, first published in 1968. “His attitude towards things and people around him may be one of criticism, it cannot be one of superfluous or pedantic indifference.”

Staying true to these words, folk characters frequent Najm’s poems; Saido Phuphay Kuttan, Taya Sohnu, Mauju Mistri, Masi Sarghi, Bhaa Shappa and, above all, Sagho Malangni, all make an appearance; sometimes they are the mouthpiece of the poet, at others they are representative symbols of society. Through their communications with each other, they bring a dramatic quality to the verse and help the poet bring his poems closer to the reality of general public life in Punjab. However, unlike the mainstream media, they avoid presenting stereotyped portrayals of Punjabis.

Two new books of Punjabi poetry by the prolific Najm Hosain Syed continue his exploration of his immediate environment

These folk characters may seem like creations of the poet, but they are taken from local lore and bring with them plenty of folk wisdom. For instance, ‘Socheen Paey O’ [Lost in Thoughts] depicts a scene where the lights have gone out because of electricity ‘load shedding’ and Masi Sarghi tells the others that the actual light is in one’s inner self. Meanwhile the speaker in ‘Mauju Mistri Di’ [Of Mauju Mistri] says: “Bahzay waylay / Chhaan kannu / Dhup syani hondi aey / Bahzay waylay, baat kannu jiwain chup syani hondi aey” [Sometimes sunlight is wiser than shade/ Just as sometimes silence is better than talk].

In both the books under review, Sagho Malangni appears at least six times and the reader starts wondering who is this Sagho with whom the poet is so preoccupied. She appears in the poems in Najm’s earlier books, too. In ‘Taer Maer Da Bhanda Chukaiway’, the poet provides an answer to this question: the all-knowing Sagho Malangni is not a common woman and not less than a mystery. Nobody really knows where she came from or her identity. She mixes with all and is friend to all and sundry. She is, in essence, a symbol of Punjabiat and one of the poet’s many creations that reflect Punjab’s social milieu: “Saghar jaat di jatti jay rajputanay di / Zraa vaderi hoee / Ghar chhad nikal gaee / Desoon des phiri / Kinhu kithay milli aey Burju / Kisay nu saar nehyon / Menu tay apnay pata aey / Kum saray kardi oo” [She belongs to Saghar caste of Rajputana / A runaway child / A wanderer / Whom she met and where / Nobody has an inkling / I just know that she does all kinds of work].

Folk characters frequent Najm’s poems; Saido Phuphay Kuttan, Taya Sohnu, Mauju Mistri, Masi Sarghi, Bhaa Shappa and, above all, Sagho Malangni, all make an appearance; sometimes they are the mouthpiece of the poet, at others they are representative symbols of society.

Another distinctive aspect that sets Najm’s poetry apart is the dramatic effect he manages to create. Many poems in the two books are dramatic, and some are dramatic monologues to be exact, such as ‘Wekho Mian Ji’ [Look, Mian Ji], ‘Puranay Retired Professor Uzar Din Da Third Lecture’ [Third Lecture of the Old Retired Professor Uzar Din], ‘Kul Sun Leo Jehri Mein Keeti Babay Sirajay Naal’ [Listen to What I Did to Baba Siraj] as well as ‘Chalo Chalye’ [Let’s Go] and ‘Hun Apnay Ghar Da Kam Nahi Mein Kardi’ [I Don’t Do Domestic Chores Anymore].

Najm has his own reasons for adopting this technique. “Why the poet seeks a dramatic mould of presentation, often echoing the everyday conversation, songs and riddles of common people, is because he knows that the social context is the best guarantee for artistic objectification of experience,” he writes, again in Recurrent Patterns in Punjabi Poetry. “The poet is essentially a dramatist who seeks to convey to his audience a uniquely personal experience through the medium of shared experience.”

In both these books, Najm takes up social and political themes besides class struggle and contemporary world matters such as homelessness, the changing times and their effects on the life of the common man. The poem ‘Chitawni’ [Warning] discusses the reality of the book called Bahishti Zevar [Heavenly Ornaments] written by Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanvi. It tells how the book is a means of making a wife more home-centric to serve her husband, her worldly god. In the poem, Najm says: “Wich dasya gya aey / Kinj apnay khudawand nu / Deenh raat ohda apna banaya bahisht wikhawna aey” [The book shows / How to show your husband / The paradise of his own making, night and day].

‘Gawan’ [Song] and ‘Zorawar’ [The Powerful] have political themes, whereas ‘Daarrhi Aam Hoee’ [Beard in Vogue], take up the themes of changing social conditions and the greater influence of religion on the life of common folks: “Daarrhi aam hoee / Khaas khaas khaskhasi vi / Lammi laam hoee / Kithay romali kithay taulia / Koi baoo koi aalam aulia / Gandh kup hath nup puls policy / Turo, traffic jam hoee” [The beard is in vogue / The thin one has also got longer/ It comes in various shapes / It’s equally common among those / Having Western or religious education / Measuring it is the new policy / Move on, life is stuck].

The reviewer is a member of staff

Dharat Samandar Rasan Galakdi

By Najm Hosain Syed

Suchet Kitab Ghar, Lahore

ISBN: 978-9695571105

120pp.

Taer Maer Da Bhanda Chukaiway

By Najm Hosain Syed

Suchet Kitab Ghar, Lahore

ISBN: 978-9695571099

111pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, September 30th, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.