FOR a party that has spent two decades galvanising a short-changed electorate, the PTI’s policy promises and manifesto fail to recognise a simple truth: politics is the art of the possible. If so, this articulation either reflects the party’s lack of policy experience or a what-ever-it-takes approach to power. That’s not new in Pakistani politics but it’s not a naya Pakistan either.

The problem with the latter is not just moral. It is also that such promises lead to great expectations of delivery — delivery, in one term, by a first time incumbent with no policy experience, likely in a coalition government facing a hung parliament.

Take, for example, the PTI promise of a welfare state. The experience of both rich (GCC) and poor countries (Latin America, Africa) shows the path to a sustainable welfare state is not singular or proven. In most cases, policy intervention to enhance social outcomes led to unsustainable fiscal deficits and debt levels, not to mention deeply rooted public expectations — a fast-growing population means the gap between revenues and spending kept rising as more and more was required for social welfare. This now requires years of painful fiscal retrenchment to remedy, often with IMF support.

Hence, the Nordic countries’ success in marrying capitalism with a welfare state is the exception not the norm. Factors behind their success include high income taxes that yields 20-26 per cent of GDP and equals 65-70pc of the total tax take due to high marginal income tax rates (40-60pc) and high tax compliance.

Promises lead to great expectations of delivery.

The latter is helped by a well-documented economy where employers deduct income taxes at source and self-filers are unable to evade given high financial inclusion — almost everyone over the age of 15 in Sweden, Norway or Finland has a bank account; 90-95pc have a debit card; and 60-75pc save in a financial institution. It is this availability of verifiable information from third parties which makes evasion difficult. What also helps is the employment structure: services employs 75-80pc in Sweden and Norway; agriculture is less than 5pc.

In contrast, in Pakistan, direct taxes yield just 4pc of GDP due to lower income tax rates (20-30pc) and weak compliance — less than four million out of the 94m employed are registered payers. This is not just due to weak public institutions and the lack of a tax culture but also weak financial inclusion. In 2014, just 13pc of over-15 Pakistanis had bank accounts; even fewer (3pc) had a debit card or saved in a financial institution. Then there is the employment structure — in FY14, 44pc were in agriculture where documentation is so poor that 90pc of farmers claim to own less than 12.5 acres (the tax threshold).

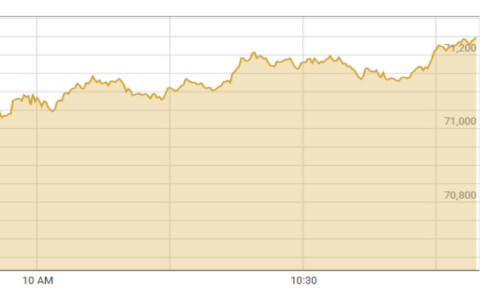

Meanwhile, the problem with focusing on lofty ideals is that it detracts focus from binding and immediate challenges. The burn rate of net State Bank foreign exchange reserves over the last 12 months rose to $575m in May. The stock fell further to $9 billion end-June — that at a time when oil is up and gross external financing needs, including the current account deficit, are over $25bn.

This explains the focus of market participants, investors and economists on a post-election IMF programme. However, there is precious little from the PTI on measures to reduce reserve burn or approaching the IMF. Even where the manifesto’s focus on higher tourism and foreign investment is concerned, neither is a function of reforms and investment alone. The political environment matters; so does FATF and relations with the West, home to the largest pools of the private capital/savings it wishes to attract. Further, there is significant lag between reforms and higher investment and tourism. Meanwhile, as the fall in forex reserves shows, time is not what Pakistan has.

The reality is that the policy choices available to the new government centre narrowly on expenditure restraint — revenues take time. Even here, devolution implies nearly 40pc of government spending is from the provinces.

Hence, without winning the provinces, fiscal retrenchment will fall to the central government. Here too, an activist judiciary could challenge measures that are in the centre’s domain. Case in point is fuel prices. Since January 2016, international oil prices are up over 200pc in rupee terms while domestic retail fuel prices have been adjusted by not even half that amount. This backdrop is hardly a start to delivering on 10m jobs and 5m housing units.

The issue is more than electoral heartbreak. Without managing expectations, Imran Khan risks becoming the Barack Obama of Pakistani politics — the promise of change could bring him to office but the lack of it during his term could aid a fourth force’s rise, perhaps the one we saw deployed on Islamabad’s borders late last year.

The author is an economist.

Published in Dawn, July 24th, 2018