Amin woke up in the middle of the cool December night in the hotel he was staying in Karachi on Shahrae Faisal. He was finding it hard to breathe. What was that smell, he recalled thinking.

Smoke! Suddenly he was aware of chaos and noise coming from outside his door. He heard screams too. Utterly disoriented, Amin stumbled towards the room door. Reaching it, he unlatched it and opened it. Smoke came billowing into his face. Slamming it shut immediately he looked around, now frantic.

He quickly wet a towel under the bathroom tap and covered the opening under the door with it. He wet another smaller towel to cover his nose and mouth. His thinking was still impaired, but instinct told him to rush to the big window. He slid it open. The second floor window of his room overlooked the swimming pool. Someone yelled out to him to tie his bed sheets to the window curtain and use it as a rope to climb out. Pulling the sheet off the bed, he did so and unsteadily climbed out on the ledge.

The ledges were speckled with shards of glass as some people in their panic had broken the window panes by throwing furniture at them. Women and children were crying.

Winter months seem to attract more than their share of fires in Karachi and there seems to be a dark edge to this phenomenon. But everything else about them — our planning for them, our responses to them and our inability to learn lessons from them — is hardly seasonal

A family on the ledge one floor above him was trying to climb down. The mother was squinting and crying about her missing glasses. The father was carrying a baby and the mother was clutching the hand of a petrified little girl. Amin called out to the father to toss the baby to him. The father above threw the screaming baby his way, wrapped in a sheet. Amin took the catch but it unsteadied him enough to make him fall backwards. Hitting his head on the first floor ledge on his way down, he fell in the swimming pool with the baby still in his arms.

Someone plucked the child from his arms and pulled him out. He vaguely recalled being lifted on to a stretcher as he saw someone throw down a mattress to jump on but missing the mark. He realised it was the mother of the child. She couldn’t see without her glasses. As he was being rushed towards an ambulance, he also saw many other hotel guests running outside. Everyone was running away from the building.

Not everyone though. He saw some men in red — or was it orange? — running in the opposite direction, going inside. Crazy, he thought, before succumbing to unconsciousness.

Amin was one of the lucky ones. Twelve people, including five doctors who were staying at the hotel, lost their lives in the fire and 75 were injured. That was in December 2016. But the panic and tragedy of fire accidents are all too regular and familiar to people who follow the news in Pakistan.

According to an estimate, fire incidents or accidents cause property losses and insurance claims worth Rs 400 billion annually in the country. Big cities all over Pakistan witness frequent fire incidents but the basic factors leading to the fires remain shrouded in mystery. Most of the time it is all said to be due to a wiring fault or short-circuit.

In the case of this particular fire at the four-star hotel, there was talk of the hotel having an outdated fire safety system along with faulty wiring which the management had failed to fix. A case was registered by the police against the owners and management of the hotel. The First Information Report (FIR) cited criminal negligence, carelessness and failure to follow the safety plan for emergencies. The hotel management was also held responsible for not informing the emergency services in a timely manner. It took firefighters over three hours to contain the fire.

It emerged that the fire had started in the kitchen on the ground floor. It spread, trapping many hotel guests in their rooms. Many guests claimed that they had learned about the fire themselves instead of hearing a fire alarm or being informed by the hotel management. They said when they had tried calling the reception desk there was no answer.

The hotel also lost a staff member who had saved many guests before succumbing to suffocation himself. The hotel management said that the entire incident grew out of control due to the guests panicking. They said there was a fire alarm system in place but after going off for a few seconds it failed due to the wires burning up because of the short-circuit that started the fire in the first place. If the guests didn’t get an answer from the reception desk, they said, it was only because that area had filled up with smoke and the staff was helping out in the evacuation process. The management insisted they held regular fire drills and the building had as many as three emergency exits from where most of the 600 guests managed to escape. “Otherwise there would have been more fatalities than 12,” said one management representative.

In February 2017, police submitted the final charge sheet in the Regent Plaza fire case stating that the fire safety system in the hotel, installed over 20 years ago, was outdated. A news report in Dawn stated that the hotel’s chief executive officer, managing director, chief security officer, chief engineer and supervising engineer had been booked for manslaughter.

Many months passed and the hotel remained closed. But it quietly reopened for business after some nine months. Nobody asked what became of the case.

WHO CARES ABOUT SAFETY ANYWAY?

Part of the problem is the usual nonchalance with which Pakistanis treat safety hazards. There are regulations in place to prevent outcomes such as the Regent Plaza fire but these are seldom acted upon or enforced.

Genuine causes for fire hazards are aplenty. A surveyor who works with an insurance company to assess the extent of losses after a fire incident at any building fire provides an overview to Eos. Poor maintenance, not cleaning cable or panel ducts regularly and inflammable objects lying around near electric wires are all fire hazards. Contact of “water on naked wires or voltage fluctuation can lead to genuine losses due to short-circuit,” he adds.

Machines and motors heating up because of overloading can also lead to fires. Normally machines run on 220 watts but if there is a wire-break and there is no earthing or a neutral phase, the voltage can shoot up to 440 watts. This usually occurs when there is rain, he says.

Locked godowns with running air-conditioning or refrigeration and inflammable paint may also result in a disaster. Nylon or polyester can create static charge, particularly in dry weather. And the sparks may turn into flames, the insurance surveyor points out.

About the many fire incidents in the city, the vice president of the same insurance agency agrees with the surveyor that housekeeping plays a big part. “Maybe they don’t have a proper garbage disposal system and the fire was just caused by a carelessly tossed cigarette stub,” he says.

FIRE SAFETY PROVISIONS

According to the Building Code of Pakistan — which since 2016 also includes fire safety provisions — all multi-storey buildings should be constructed on roads as wide or broader than 30 feet to allow access to emergency and fire vehicles. Escape facilities consisting of doors, walkways, stairs, ramps, fire escapes and ladders, arranged in accordance with the general principles of the Building Code of Pakistan, are meant to be in place. Emergency and fire vehicles should be able to easily access the emergency exit staircase of the buildings.

Each staircase should be clearly marked by clear and easily legible exit signs. All buildings should have one multi-purpose dry chemical powder 6kg-fire extinguisher for every 2,000 square feet of floor area. Also, two 6kg-fire extinguishers should be placed on each floor.

Buildings taller than four storeys should have a pressurised internal fire hydrant system with an independent overhead tank of at least 7,500 gallons and an external underground water tank of 15,000 gallons. Automatic fire alarm systems are mandatory, along with a sprinkler system. The sprinkler system should be connected to the pressurised internal fire hydrant system.

By law, there should be regular inspection, servicing or recharging of portable fire extinguishers, the servicing, modification or recharging of fixed fire extinguishing systems, and the servicing or modification of fire alarm or fire communication systems.

Cooking ranges in kitchens are supposed to have hoods. There need to be regularly maintained and sprinkler systems in all the rooms, halls, corridors and the internal car parks need to be regularly tested. Separate air handling units for various floors are supposed be provided so as to avoid the hazards arising from the spread of fire and smoke through the air-conditioning ducts.

Fire drills should ideally be conducted once every three months and on each shift to familiarise the entire staff with the procedure. So they may be conducted in the morning, in the afternoon and in the evening.

The domino effect of one fire incident doesn’t end there. It’s a bigger game. Usually “when one factory is set ablaze, and they get their claim, there are more factories owned by the same people for which they want to claim huge losses, too,” adds the officer.

All fire escape doors and exits should have self-closers and all smoke alarms should be shrill enough to be audible in all sleeping areas.

On paper, everything has been thought of and procedures laid down. But like most regulations in Pakistan, they are easily bypassed with a little bit of greasing of palms and with officials looking the other way.

The consequences of this lackadaisical attitude are often terrible, as the Baldia Factory fire, which claimed the lives of at least 258 factory workers in 2012 showed. That fire, alleged to have been a deliberate act of arson, would not have claimed so many lives had some basic fire safety regulations been followed by the factory.

LETTING THE FIRST RESPONDERS DOWN

Those directly in the line of fire, are the first responders such as the Fire Brigade.

“Whenever there is an incident of fire, you see people running away from there. But firefighters will be running towards the fire,” Tehseen Ahmed Siddiqui, the chief fire officer of Karachi’s Fire Brigade Department (FBD), tells Eos. “We respond to some 4,500 fire incidents annually, with more in winters as opposed to summer time,” says the fire chief.

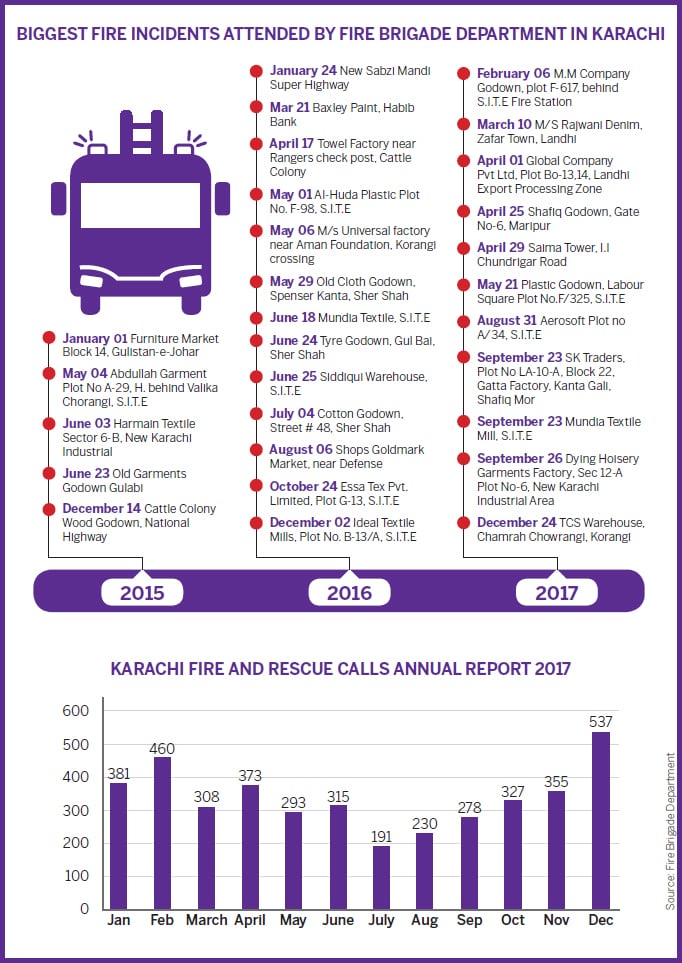

In December 2017 alone, there were a total of 537 fire incidents which the FBD responded to. The biggest incidents — called ‘Stage Three Fire Emergencies’ — of 2017, included fires which broke out at the M.M. Company Godown (Feb 6), Rajwani Denim in Landhi (March 10), Global Co Pvt Ltd (April 1), Shafiq Godown in Mauripur (April 25), Saima Tower on I.I Chundrigar Road (April 29), Plastic Godown at SITE (May 21), Aerosoft Plot SITE (Aug 31), S.K. Traders Plot at Shafiq Mor (Sept 23), Mundia Textile Mill at SITE (Sept 23), Dyeing Hosiery Garments at New Karachi Industrial Area (Sept 26) and at the TCS Warehouse at Chamrah Chowrangi, Korangi (Dec 12).

But the lackadaisical attitude extends beyond private companies to government planning as well.

The central fire station of Karachi, known as Al-Markaz, was built in 1914. It lies a walking distance from Civil Hospital’s Burns Centre. There are 22 fire stations that come under the FBD including Al-Markaz, which respond to all fire emergencies, although Karachi Port Trust (KPT), Defense Housing Authority (DHA), Cantonment Board Clifton (CBC), Pakistan Air Force (PAF) and Pakistan Navy (PN) all have their own fire brigades. “They may have more manpower, superior vehicles and equipment but it is Karachi’s FBD that is usually going in to brave the blazes and put out the fires in their areas too,” says Siddiqui.

The fire chief says that there should ideally be one fire station per a population of 100,000. Instead, in a city of about 20 million, there are only 29 fire stations of which four are dedicated to military bases. The FBD has only 19 fire tenders and four snorkels — of which only one is operational — along with a rescue and ladder truck.

“There would be only one firefighter from our department holding a water line or hose whereas you will see six of KPT or CBC men holding a line. But they don’t seem to have the required training or morale,” says the fire officer, shaking his head.

But morale is different from being provided the requisite training and resources. The FBD men will make their way into a burning building without masks on to protect from smoke inhalation, covering their nose and mouth only with a handkerchief, the FBD chief boasts. “They are that charged up in emergencies,” Siddiqui says. But then comes the damning admission. “That is how our department has lost 24 lives in the line of duty and have many injured,” he admits.

PLAYING WITH FIRE

Aside from the lack of preparedness inflicting disaster-readiness, however, there is an even darker side to the cases of fire incidents.

The police officer investigating fire incidents is a very nervous man. He requests anonymity for the fourth time during our interview. I assure him and prod him to speak. He begins by showing me an SMS message he has received from a high-up in the Sindh government. It is a request, or rather an ultimatum, for a copy of the first information report (FIR) that needs to be submitted to the surveyor or insurance company after a fire incident at a godown. “I hope you can oblige rather than my having to go elsewhere,” reads the message.

“They play with fire. It is a game for them,” he finally speaks in a hushed tone.

“Look, I have a family to take care of. My children are young,” he says. “So I do oblige them,” he admits while reaching for the paper napkin to wipe the sweat accumulating on his forehead. “Maybe speaking to you will lift some weight off my chest,” he says.

“Ninety percent of all fire incidents here are deliberate. There are very few accidents,” he claims.

The police officer explains that most reported incidents are arson cases but they are expected to put them down as ‘accidents’. “They need the insurance money,” he explains.

The reasons can be varied. An order or consignment may have been cancelled and the seth [factory owner] needs to make up for his losses with insurance money. Or a manufacturer might have produced inferior quality material that a buyer rejected. So the factory owner plots to set it ablaze to receive insurance money and cut his losses.

On December 12, 2017, fire tenders reached a warehouse at Chamrah Chowrangi, Korangi, soon after an alarm was raised during a fire incident. “We were informed that the fire broke out only half an hour ago,” says a firefighter. But then the blazing building collapsed.

“How is this possible?” asks a first responder also present at the location. “It couldn’t have been burning for 30 minutes for it to collapse like that,” he says. “There is a sublimation process. It takes burning for more than six hours, at 500 degrees Celsius, for the concrete to segregate from the iron bars,” he explains.

These are questions that never make it to the police report.

Do insurance companies facilitate and readily pay the claim amount?

“Before insuring a building we have an inspectors’ team visit it to check if they have fire extinguishers, fire buckets, fire alarms and other safety standards in place,” says the vice president of an insurance agency who spoke to Eos on condition of anonymity. “After a fire we work on the advice of our surveyor. If his report is clear, we do pay the amount.”

When an insurance surveyor from the same firm is asked whether buildings and factories are ablaze deliberately, the surveyor says that it is very difficult to determine what happens in those cases. “We can easily see if someone is claiming 10 million in rupees from an insurance company but only have material worth 500,000 rupees destroyed lying on one side. That is, of course, a fake claim,” he says. He skirts the real question being asked.

According to the police officer, the insurance surveyors have no choice either. “Just like I worry about my family if I say no, they worry about their business because the people asking for the claim have many more companies and consignments insured with these firms. When they threaten to go to some other company for insurance cover, the insurance companies also comply,” he explains.

And it is not just one or two businesses that may pull out. The insurance firm risks breaking ties with the entire business communities that the business owner belongs to, for example, the Chinioti biradari, the Punjabi Saudagaran, etc, the police investigator points out.

The domino effect of one fire incident doesn’t end there. It’s a bigger game. Usually “when one factory is set ablaze, and they get their claim, there are more factories owned by the same people reporting fire incidents for which they want to claim huge losses, too,” adds the officer. Some owners ‘suffer’ fire incidents every year, he says.

The owners will cover up with excuses as thin as blaming voltage fluctuations as the cause of fire, or they will delay before calling the fire brigade so they can blame the fire department’s tardiness, he adds.

An interesting circumstantial bit of evidence backing up the police investigator’s claims is that most fires erupt in December. The timing is no coincidence he says; December is year-end for closing accounts and balancing the sheets. “Their shortfalls they make up for by burning things and claiming losses,” he claims.

In 2017, of the 4,048 fire incidents in Karachi, 537 took place in December. In fact, 1,733 of them took place in just four months from November to February, the coolest months of the year. Unlike other cities up north, Karachi is not cold enough for wide usage of electric heaters either.

A senior executive director of an insurance agency who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity tells Eos that the firm depends on the surveyor’s report where he has determined the cause of an incident of fire to fulfill a claim.

I ask an insurance surveyor if he has ever been threatened to tailor his report after a fire.

The surveyor becomes silent. “Look,” he says, “This is Pakistan. I may assess damage at a certain amount but the people filing the claim may want me to raise the amount. It happens all the time.

“Mostly they succeed. Tell me, what can a surveyor do when a tycoon has the fire department and the police station on whose reports we also work, on their side already? We can’t stand up to them alone,” he says before falling silent again.

The writer is a member of staff.

She tweets @HasanShazia

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 14th, 2018