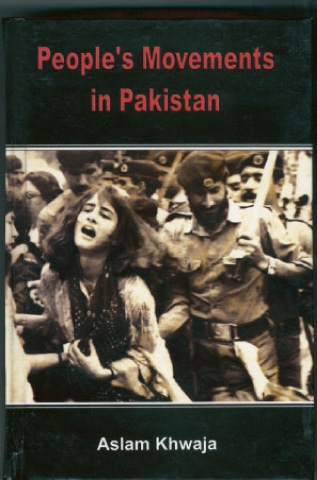

Steeped in the tradition of simple-looking but wise Sindhi fakirs, Aslam Khwaja wanders across his land, taking note of crowd-set courts along the way, and picking up stories of his people’s struggles for democracy, socio-economic rights and self-realisation. His book, People’s Movements in Pakistan, tells us of the sacrifices made by a large number of men and women, their modest successes and their terrible heartbreaks, and offers many a lesson to all those who have the courage to pursue their dreams.

Khwaja begins with a concise account of the Balochistan imbroglio, from the opening part of the Baloch ballad to the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti. We are told of the treaties the British signed with Kalat, the promises made to the latter on the eve of the British withdrawal from the subcontinent, the circumstances under which the state was made to accede to Pakistan, how Gen Ayub Khan’s regime went back on his pledges to the Zehri sardar, and how the first elected government was demolished. Using his access to some of the actors of the 1973 uprising, especially to Asad Rahman, the author throws fresh light on the role of the ‘London group’ of students from Punjab, and supplies some links in Balochistan’s tale of endless woes that are not commonly known.

The longest chapter, nearly one-third of the volume, is devoted to the democratic struggle against Gen Ziaul Haq’s dictatorship. It begins with the launch of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) in 1981 and concludes with a summary of the first steps to offer relief to workers, students and women announced by Benazir Bhutto on becoming prime minister in December 1988.

Revisiting the stories of ordinary Pakistanis who had the great courage to stand up and fight against oppression

After describing the roles played by the various opposition parties in starting the MRD, the author tries to compile a day-by-day record of the agitation in different parts of the country — though in greater detail in Sindh — and also takes notice of differences among the MRD parties on some constitutional issues. Despite a few gaps in the narrative, students of this part of Pakistan’s history will find considerable material on which to build their research.

The overview of the trade union movement, the second-longest chapter in the book, is considerably rich in information about the rise of workers’ organisations in Pakistan and their struggles for labour’s uplift. Khwaja begins with a brief survey of factories and village crafts in Sindh during the 10th to the 17th centuries and traces the founding of cotton-ginning and textile units in Punjab in the last quarter of the 19th century. Workers started organising themselves into unions soon afterwards and the first strikes took place in the 1890s. Extreme action was sometimes resorted to when relevant laws were changed. Notice is also taken of the political parties’ interaction with trade unions.

The author brings to light the history of the trade unions’ fight for their economic rights to the 1970s while giving special attention to the tobacco workers’ agitation in the 1960s. The period of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s government (1972-77) is covered in some detail, especially the June 1972 clashes between the workers and the government in Karachi, which many thought marked the beginning of the suppression of the long working-class movement that had begun in the 1960s. While covering the Gen Zia period, the author takes special note of the massacre of workers at the Colony Textile Mills and the regime’s anti-labour policies. At the end of the chapter he provides a table of labour strikes from 1947 to 1977.

Peasant movements are dealt with province-wise, beginning with Sindh. The chapter includes a fairly detailed account of the struggle and martyrdom of Shah Inayat and a survey of the work done by the Sindh Hari Committee in its various incarnations until 2007, along with brief life sketches of prominent leaders of the committee. The author then adds short notes on bonded labour, the Tando Bahawal case in which an army officer was hanged for the killing of nine villagers, and the courageous resistance to wadera raj shown by Munnoo Bheel and several other bonded workers.

While recalling peasant agitations in Punjab since 1936, the author concentrates on the 1943 resistance to an increase in malguzari [land revenue] tax, the first national Kisan conference in 1948, followed by conferences in 1952 and finally the Toba Tek Singh conference in 1970. A survey of the struggle of tenants settled on military farms in Punjab, which is still continuing, follows. Some extremely useful references have been made to peasant agitations in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

The chapter ‘Art, Culture and Literature’ is full of information about the struggles of writers, artists and cultural workers and their suppression by the state. The highlights are: the arrest of communist workers soon after Independence, the Bangla language movement, the rise of the Progressive Writers’ Association and its being banned, the suppression of the Sindhi language, the formation of Awami Adabi Anjuman, some criticism of leftist writers’/intellectuals’ attitude towards the military operation in East Bengal, the Sindh Language Bill, the campaign of the Zia regime to hegemonise literary and cultural organisations, the theatre of defiance led by Dastak, Zamir Niazi’s chronicle of the plight of the press, and a short survey of books written in prison.

As in other chapters, while discussing women’s struggle for equality and rights, Khwaja includes in the definition of ‘people’s movement’ the work of organisations established to defend and advance women’s causes, such as the Democratic Women’s Association, All Pakistan Women’s Association, Women’s Action Forum, Shirkat Gah, Tehreek-i-Niswan, and the Sindhiani Tehreek. Also included is the work of the commission on women’s rights. Further, he offers brief references to outstanding woman activists, from Shanta (Mrs Jamaluddin Bokhari) and Rana Liaquat Ali Khan to Hajra Begum, Perin Bharucha, Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan, Alys Faiz, Asma Jahangir, Hameeda Ghanghro, Shahida Jabeen, Begum Abbasi, Malala Yousafzai and Parween Rehman. The price that many of these women had to pay for their views and their work is also briefly touched upon.

The author’s desire to record events on a daily basis finds relatively fuller expression in the chapter about the travails of the press and journalists. In addition to taking note of the journalists’ movements against the Press and Publications Ordinance 1963 (the first one), for implementation of the wage board award, and against the sacking of Musawat employees, Khwaja records the persecution of journalists by both state and non-state actors, from the early days of Independence to the murder of Saleem Shahzad. If this is a complete record of actions taken against newspapers and their staff, its value cannot be exaggerated.

In the final chapter Khwaja recalls the circumstances in which student organisations — Muslim Students Federation, East Pakistan Students League, Democratic Students Federation, National Students Federation, Baloch Students Organisation, Peoples Students Federation and All Pakistan Muttahida Students Organisation, et al. — were formed, the high points of their agitations, and the state’s actions against them.

Khwaja’s book is a mine of information not only about what are somewhat generously described as ‘people’s movements,’ but also about the strivings of a large number of organisations and a larger number of individuals who struggled for years — often at grave risk to their lives — for justice, democracy and individual and collective rights. It should become a standard book of reference for students of politics and Pakistan’s social history if — while preparing the next edition for the press — the long MRD narrative is split into sub-chapters, the more glaring gaps in accounts relating to workers, peasants, women and students are filled, footnotes and sources of information are added, the author is persuaded to check his iconoclastic zeal, and the editor pays a little more respect to the Oxbridge community’s sensibilities.

People’s Movements in Pakistan

By Aslam Khwaja

Kitab Publishers, Karachi

648pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, March 19th, 2017