THREE more individuals sentenced to death by military courts have had their sentences stayed by the Supreme Court while the appeals are to be heard.

The convicts and their families have raised a disturbingly familiar set of objections: the accused were not allowed to pick their own lawyers at the trial stage; the defence was not allowed access to the state’s evidence against them; and the families only learned of the sentences via press releases.

The latest appeals add to the dozen cases already before the Supreme Court, and for now, there is no indication which way the court is leaning — the stay of execution does not suggest innocence in the eyes of the court, merely that the sentence is irreversible and therefore the appeals process must be completed first.

What is clear is that military courts by their very design cannot ensure due process or a fair trial and that only the Supreme Court stands in the way of the total annihilation of constitutional safeguards of fundamental rights.

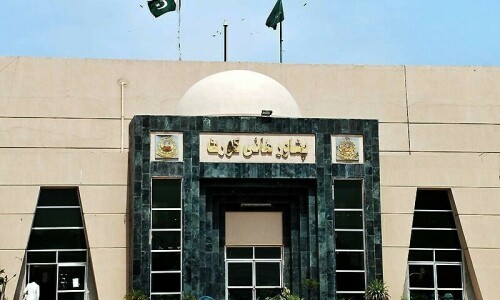

Given that the Supreme Court itself sanctified the creation of military courts for terrorism offences under the 21st Amendment, the other tier in the appeals process was not expected to produce favourable results for those seeking enforcement of their rights — the Peshawar High Court, absent any clarification by the Supreme Court about the grounds of a successful appeal, has already turned down most requests to overturn sentences handed down at the trial stage in the military courts.

Nor has the PHC generally seen fit to convert death sentences to lesser punishments. The real concern, then, is that the Supreme Court has not shown any urgency in dealing with the appeals of military court convicts.

In January the sunset clause in the 21st Amendment will mean that, barring an extension by parliament, military courts will cease to exist. It is possible that the edifice of military courts could be dismantled before the first batch of appeals is decided.

A question that is not before the Supreme Court, but ought to be asked of those who pushed for and sanctioned military courts is whether convicting 76 individuals in 18 months has been worth the price of distorting the Constitution and sabotaging the justice system in the country.

The alternative — reforming the criminal justice system — may have been more difficult and involved coordinating across many institutions and tiers of government, but such a project could surely have been achieved in two years, if the institutional will had been found. What the country is left with, instead, is a still-broken criminal justice system and military courts that are soon to expire and that will leave in their wake a host of legal complications to resolve in the appeals stage.

It truly appears to be a case of a terrible original idea compounded by predictable complications.

Published in Dawn, May 12th, 2016