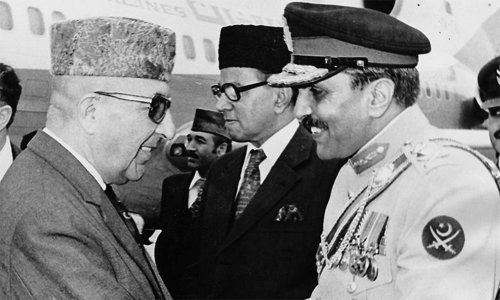

BY now the name of Gen Ziaul Haq has practically become a metaphor for the darkest decade in Pakistan’s history. The patronage of militant groups may have a longer history, preceding the era of the general whose death anniversary just passed a few days ago, but the proportions that it assumed in Ziaul Haq’s time was truly monstrous.

He is remembered for many things: the sinister laws that were passed to solidify his rule, his experiment with ‘managed democracy’ (which too has a longer pedigree but took concrete form in his time), his foreign policy, and the first steps towards economic liberalisation that were undertaken during his time. And of course his death in a plane crash, the biggest mystery of which is the cloak of silence that was dropped on it.

The biggest legacy of the general is the contradictions he left Pakistan mired in. The country was in a close and deep alliance with America, while at home the general’s regime stood on the shoulders of extremist elements for its own legitimacy.

Economically, he tried to reverse the legacy of both his predecessors, by opening up the economy to encourage competition and roll back the nationalisations and halt the growing role of the state in every area of economic life. But his economic policies left the country trapped between a rentier business elite demanding more protections and foreign creditors demanding more openness.

The general was caught between his dreams and reality, eventually losing touch with both. Much the same fate befell Musharraf, although in his case when the time came to choose, he opted to cling to his dreams and jettison his contact with reality. The results are clear to see.

Gen Zia was caught between his dreams and reality, eventually losing touch with both.

Today Zia is dead and nobody in the country, including in the army that he led, is interested in asking who did the dirty deed. Musharraf, on the other hand, has lived to dream of electoral victory on the promise of confronting the Taliban when he cannot even muster the courage to face the court trying him for treason, or even win the Sind Club election let alone a parliamentary one.

The general who wanted to rule forever, and was laying down the architecture of eternal dictatorship in the days following the dissolution of the Junejo government, was scared stiff of a 35-year-old woman whose father he had executed and whose popularity he could do nothing to extinguish. Those who met him in the twilight of his life describe a man who was obsessed with Benazir Bhutto and couldn’t complete a train of thought without mentioning her at least once.

He came to power promising elections, he left promising elections. By May 1988 it was clear that any election would only be won by the PPP since it was the only party capable of fielding a candidate on every seat in the country, and the general’s men took to giving private assurances to all they met that the general’s regime was here for a lot longer than being conveyed in public statements. That is when his plane exploded, precisely at the time when his dream of being in power indefinitely must have seemed closer to him than ever before.

His infamous Eighth Amendment, used by him to dismiss a government elected under his own rules, was subsequently employed to dissolve the PPP government, and also the government of his own protégé, Nawaz Sharif. All components of the general’s rule and his legacy were at loggerheads with each other.

One very interesting dimension of the general’s rule was its impact on the civil service. The rise of Ghulam Ishaq Khan was an emblematic achievement of his rule, drawn by a marriage of convenience. Mr Khan was a man of many shades, skilful at building a network of support for himself within the services, keenly aware of where talent lay, supremely loyal to his own people, but clumsy at his attempts to engineer a political outcome in the great civil contests that began following the general’s death and completely beholden to GHQ for his position.

Who remembers the network of civil servants he pulled into a tight network around him? There was A.G.N. Kazi, the master administrator who held almost every important economic post in the country, V.A. Jaffery, the quiet and temperate technocrat of sorts and so many others. And circling in their midst was the ever present Mahbubul Haq, the thorn in Khan’s side, whom the general had taken a liking to despite Khan’s best efforts. Mahbubul Haq served as finance minister twice, once in 1985 and then in 1988, replacing Wattoo once the Junejo government had been dismissed. But that is another story.

The point is this: this entire network, which continued wielding considerable power so long as their benefactor enjoyed a good rapport with GHQ, was swept away once Khan was gone from the scene following his fatal clash with Nawaz Sharif in 1993.

In politics too, the general opened the door to so many of the same politicians who are today vilified as emblematic of everything that is wrong with civilian rule. Nawaz Sharif first used the power of money and mass advertising campaigns to win in the 1985 election. Who subordinated civil institutions to play the role of dividing up the political space between loyalists and opportunists? Who wanted to create Mehran Bank and for what purpose? Was Jam Sadiq Ali really such a big improvement on Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi in Sindh? Who gave us the IJI and how was it created?

So many questions, all with a direct relevance to our times, all the legacy of the general and his men, who toyed with the country with the wiles of a schoolboy. So many memories to rake up every time this infernal anniversary passes us by. And so many anniversaries in every year.

The writer is a member of staff.

Twitter: @khurramhusain

Published in Dawn, August 18th, 2016