GIVEN recent by-election results and a groundswell of support for the PTI, questions around the fate of other parties are more relevant than ever. It remains worth asking what does the future look like for the two major political parties that still have national ambitions, the PML-N and the PPP.

For some, this may simply be a question of the fate of their leadership and their families. The future of the parties is tied to how well the next generation of leadership is able to adapt and keep the party spine of first and second-rank politicians in place.

This dynastic view of survival seems to pay reduced dividends with each subsequent generation. The PPP’s electoral base has shrunk geographically in the preceding years over the course of two leadership transitions (from Benazir to Zardari, and with the ongoing one from Zardari to Bilawal).

Shehbaz Sharif too has struggled in keeping the PML-N base intact and it increasingly looks like the disqualification of Nawaz from active politics has caused partly irreversible damage to the PML-N’s electoral potential.

Do these trends suggest a move towards one party domination across not just one, but several future elections? PTI partisans remain convinced that a two-thirds majority, if not more, is within their grasp if free and fair elections are held soon.

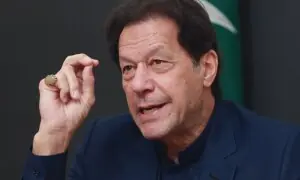

There is a reasonable basis to these expectations given the success in the by-polls. PTI candidates did very well across Punjab in the provincial assembly ones, and Imran Khan decisively won nearly every seat he contested.

However, Pakistan’s political history tells us that domination by one party or the establishment tends to run its course; sometimes through the pressure of the citizenry and other times through the intervention of the military: 1969 and 2007 are examples of the former, where citizens mobilised to weaken an incumbent regime and pave the way for a new political dispensation; 1977 and 1999 are examples of the latter, where a dominant party was elbowed out under the risk that it was becoming ‘too dominant’.

If there’s one aspect of our political landscape that remains reasonably constant, it is that no one arrangement can paper over all of society’s political differences.

If there’s one aspect of Pakistan’s political landscape that remains reasonably constant, it is that despite best efforts, no one arrangement can possibly paper over all of society’s actual political differences. There are many examples of this, but a recent one is the previous version of the ‘same-page’ regime between 2018 and 2022.

Also read: Dynastic politics

Leadership disqualifications and NAB cases kept opposition parties at bay, but they remained relevant in by- and local elections throughout this period. Similarly, even with the ouster of the PTI and the setting in of another ‘same-page’ regime, the political prospects of the new opposition party have only grown more vibrant.

Part of this simply has to do with anti-incumbency sentiment. With rampant inflation and unmet expectations, voters are likely to punish whoever is in government either by voting for the opposition party or by staying home.

A close look at the by-poll results in Punjab reveal that this is at least part of the story in some constituencies. The PTI’s vote share has held firm, while the PML-N’s has gone down in tandem with the overall turnout. This is also tied to the ‘sales pitch’ of the parties: with difficult economic circumstances, parties in government have nothing to take to the voters, while opposition parties can promise better days, self-respect, freedom etc.

In part, then, the immediate future of the PML-N and PPP is tied to the level of voter apathy at the next elections, and what the PTI will face once it is back in government and performs at whatever level.

But there is another reason for the continued existence of multiparty competition. And that relates to the tangible social differences that exist in Pakistani society, much like they exist in any other society. Can one party represent all conflictual interests within one broad tent? Can the same party adequately represent Pakhtuns and the Baloch in Balochistan? Urdu-speakers and Sindhis in Sindh? Rural and urban middle-classes in Punjab? Deobandis and Barelvis across the country?

Does it have enough space to accommodate all constituency politicians, who’ve made careers fighting elections with each other and cultivated followers in their own small pockets?

Temporarily, it is possible to unite a broad swathe of the electorate under one leader, out of distaste for the status quo.

It is also possible that in the not-so-distant future, ethnic conflicts become less salient in some parts of the country as a more homogenous national identity takes root. But other entrenched differences, across economic classes, sects, and geography will likely stay perennially relevant, and will always play themselves out after some time has elapsed.

Take the case of the Indian National Congress, the oldest party in India. It mobilised the Indian masses and helped create an independent state. After independence, it controlled every aspect of administration and all the resources that the state had to offer. Yet it lost a provincial election to the communists within a decade in Kerala.

The Peronists in Argentina at one point held 139 out of 145 seats in the Lower House and 65 per cent of the total vote for the presidency. They’ve never matched that performance in subsequent elections, frequently failing to secure more than 50pc in the first round.

What this tells us is that in a country where elections determine who gets to govern, the future of the PML-N and the PPP is definitely not tied to the degree to which they can hang on to establishment support, but the degree to which they can stay relevant, legitimate, and connected within different real divisions in society.

A failure on these aspects will probably open up space for a new party, or a rebranding of an older one, or even perhaps a splintering of the dominant party. But the political system will always offer space for opposition.

The writer teaches politics and sociology at Lums.

Twitter: @umairjav

Published in Dawn, November 14th, 2022