Adeela Suleman — Not Everyone’s Heaven

Edited by Rosa Maria Falvo

Skira, Italy

ISBN: 978-8857241661

216pp.

Living in a city such as Karachi is a complex experience. Substandard living conditions aside, its hardened citizens are endlessly faced with their own mortality every time they step out of the house, becoming emotionally fraught and perpetually on edge. The city suffers at the hands of this violence, yet it also, in an odd way, feeds off of it, thriving within its embrace.

This complex relationship of human nature with violence and trauma lies at the heart of Adeela Suleman’s art, which emerges from her toxic love affair with the metropolis and, ironically, becomes her lifeline in the bid to navigate and survive it.

This basic premise is laid out, dissected, unpacked and expanded in the artist’s recent book Adeela Suleman — Not Everyone’s Heaven, edited by Maria Rosa Falvo and featuring a collection of essays and an interview. It charts the trajectory of the artist’s career over the past two decades, offering a layered investigation into her life and mind, influences and intellectual reasonings, and the countless readings her works offer in relation to the environment in which they were conceived, as well as the wider global context.

Salima Hashmi sets the stage against which the artist’s works can be neatly placed, read and understood, with a brief plotting of the socio-political atmosphere and historical series of events that nurtured Suleman’s practice. Hashmi brings special attention to the series of influences that formed the basis of Suleman’s investigations, at the centre of which is the city of Karachi and its urban political landscape, which honed her creative instincts, mental tenacity and unrelenting drive, and provided the grit and sense of activism in her work.

A book celebrates and dissects Adeela Suleman’s art which focuses on the relationship between death, violence, power and injustice

This is further elaborated by Hameed Haroon in his essay ‘The Art of Urban Resistance’. The Karachi of Suleman’s childhood and adolescence is described as a volatile warzone, yet at times this violence, grime and hardened rawness is laid out in tones of romanticisation, bordering on the fetishistic. Perhaps this is why Haroon reminds us that the artist’s engagement with the city and its cultural idioms of popular and transport art is not a superficial othering or exoticisation, but rather an insider’s perspective, coming from a middle-class life spent travelling in public transport and working with local craftspeople in a studio situated in a low-income colony.

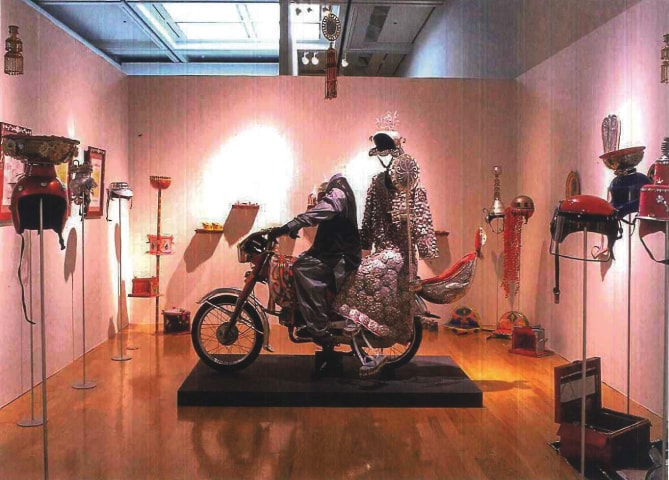

Haroon picks out a few seminal works that illustrate the trajectory of Suleman’s practice and the pulses that run through each phase of her career. Suleman begins with tongue-in-cheek depictions of the power dynamics of gender in Pakistani society and the ways in which this is manoeuvred between class, culture and religion in her breakthrough works ‘Tip Top Tea’ and ‘Salma Sitara and Sister’s Motorcycle Workshop’. This also initiated her vocabulary of found household items and kitchen utensils — tools women use within the homes, brought out into the streets to help negotiate a dangerous world.

This initial use of wit is meant to be a hopeful take on the disregard for women’s safety, but seems rather to point out our hopelessness in society, the onus of our protection thus falling on our own heads yet again. This language is further used to explore the male/ female relationship and its complexity within various contexts over the next decade or so, beyond which there is a shift in Suleman’s narrative and visual language.

Quddus Mirza, in his essay ‘Death, Migration and the Maiden’, describes this shift in terms of material and composition, “from single objects made with multiple components to installations consisting of different pieces arranged to denote a story.” However, perhaps a more potent change is an increasingly direct engagement with the concept of violence, death and terror in the global contemporary context, articulated through metaphors, symbols and myths.

The hopelessness that previously hid behind dark humour is now more directly addressed, as is our oddly complex relationship with violence as a species. This is encapsulated in the recurring symbol of the dead bird, endlessly repeated in beautiful hand-beaten metal and arranged into chandeliers and wall hangings.

Mirza’s essay moves the discussion beyond obvious influences towards a more intellectual study. To Mirza, death is a form of migration, and vice versa, which is an interesting take that, when applied to Suleman’s work, opens it up to myriad profound interpretations that go beyond such simplistic readings as ‘violence’.

By extension, the institution of marriage in South Asian cultures that the artist critiques in ‘Tip Top Tea’ becomes a form of migration (and death?) for the bride-to-be. One feels this could have been utilised as a promising interpretive tool to bring more focus to the arguments put forth in the remainder of the essay, but is abandoned henceforth. Mirza instead analyses the conceptual, formal and thematic threads and their various connotations in Suleman’s practice.

The next phase of Suleman’s oeuvre utilises history as found imagery, according to Mirza. The headless figure of the warrior seen brandishing weapons in perpetual conflict is interpreted by Mirza, through literature and myth across cultures, as the “persistence of conflict beyond physical demise, even for futile gain ... Such characters are not in confrontation with another human being, but their presence and postures reveal the permanence of violence.”

By this time, the artist has moved beyond the theme of feminism, yet her art still seems to originate from a female point of reference, where violence and power appear to have a masculine nature — as Mirza quotes Susan Sontag: “war is a man’s game… killing has a gender and it is male” — which the artist seems to temper and pacify through the use of beauty and femininity.

At this point, the glut of violence and gore in Suleman’s work reaches a frenzied climax, yet its beautification tames it to a level of politeness and grace that makes it almost compelling, and one wonders whether the artist is attempting to break us out of our desensitisation, or merely feeding further into it. This line of critique is addressed in the interview by Falvo, where she questions the artist about the fine line of turning witnesses to violence into voyeurs and silent participators.

In response, Suleman likens her work to memorials of death and violence in that they “camouflage violence with beauty. The viewer is drawn by the sheer aesthetic of the work and then pushed back by the violence it has inherited. It’s a back and forth process of realisation.” While one understands the conceptual reasoning, it becomes difficult to ignore the direct effect of the aesthetic aspect making it easier to view and digest the bloodshed that might otherwise make one instantly look away. But then again, unless we face the hard truth, we cannot begin to take actions to remedy it.

The book ends with a short piece on ‘The Killing Fields of Karachi’, the artist’s installation at the 2019 Karachi Biennale (KB). Mohammad Hanif aptly condenses the implications of the destruction of this work, of not only the silencing of truth, but the denial of art as a mechanism of spreading that truth, relegated to a status of mere wall décor by the authorities.

The response of the KB Trust’s board members further enabled the brutal censorship and, as a result — as Mohammad Hanif aptly concludes — “[Policeman] Rao Anwar becomes our culturally sensitive issue, the 444 plaques [of those allegedly extra-judicially killed by Anwar] form the basis of our country’s disgrace, and the questioning eyes of [one victim] Naqeebullah Mehsud’s father represent insolence.”

This became a sort of culmination and real-world materialisation of the artist’s narrative of death, violence, power and injustice, inadvertently proving exactly why art such as hers is a necessity.

The reviewer is an independent art critic and curator. She posts about developments in the art world on Instagram @nimrak.art

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, October 17th, 2021

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.