New Delhi’s actions in India-held Kashmir are despicable. There can be no two opinions about it. Short of war, it behoves Pakistan to take every action possible to show solidarity with struggling Kashmiris.

But does it follow that those actions are practical?

Bilateral trade is heavily tilted in favour of India with our imports five times more than our exports. And that is without accounting for informal trade that is estimated to be about twice that of formal trade. On the face of it, it appears that the ban on trade with India makes as much economic sense as political sense, especially given Pakistan’s beleaguered trade balance.

But the reality is far more convoluted than simple trade numbers or knee-jerk emotional responses.

The real picture

“The tops of many bottles, such as paint or medicine, have a polymer-based material, which is on the list of items not importable from India. Practically speaking, however, almost all that is available in the market is sourced from India,” said a trader on condition of anonymity.

“Indian companies have set up shop in Dubai, which they show as Chinese. When an order is booked and processed, its paper work indicates that the product’s origin is China. It’s a fairly open secret all along the chain. And this is not the only product, there are many others on the banned list that are imported in a similar manner,” he said.

Another importer explained the use of switch bill of lading in importing from India through Dubai. “It is only paper,” he said candidly. “The original bill of lading is for some party in Dubai. Through a switch bill of lading, the consignment shifts to our name with the country of origin no longer India.”

When it comes to small-scale firms that cannot shift vendors or absorb extra costs, commercial interests may supplant patriotism

“We will shift imports to China,” said a third importer with patriotic fervour. However, he too conceded that while he supported the trade ban and would opt to source materials from elsewhere, there were some raw materials he would have to import from India via the United Arab Emirates.

Talking about the practicality of the ban, he pointed out that several Indian companies had plants all across the world. One could be importing from Africa or Germany, but the company manufacturing the consignment would have its headquarters in India.

“We import from three different companies in India. Since the trade ban, six to seven of our orders have been cancelled,” narrated an importer and distributor. Imports from India include reactive textile dyes, 80pc of which are coming from New Delhi as they cost less and have easy raw material availability. Other imports consist of food flavours since the Indian taste profile is similar to ours and their technology is more advanced, he explained.

Import breakdown

However, he was completely in favour of the trade ban. “Yes, the cost of importing from elsewhere is higher but the difference in most cases is about 10 per cent. We can absorb this cost or adjust our prices rather than import from India. I do not regret my cancelled orders, I will simply import from elsewhere,” he said.

Walking into a branded store in a posh mall in Karachi, one can see packs of over-priced baby rompers bearing the made-in-India tag. Not only do imports of such consumer goods put unnecessary pressure on the import bill, it is galling to one’s pride to find products that could easily be made in Pakistan to be flaunting our hostile neighbour’s tag.

But these imports do not consist of the bulk of formal trade with India.

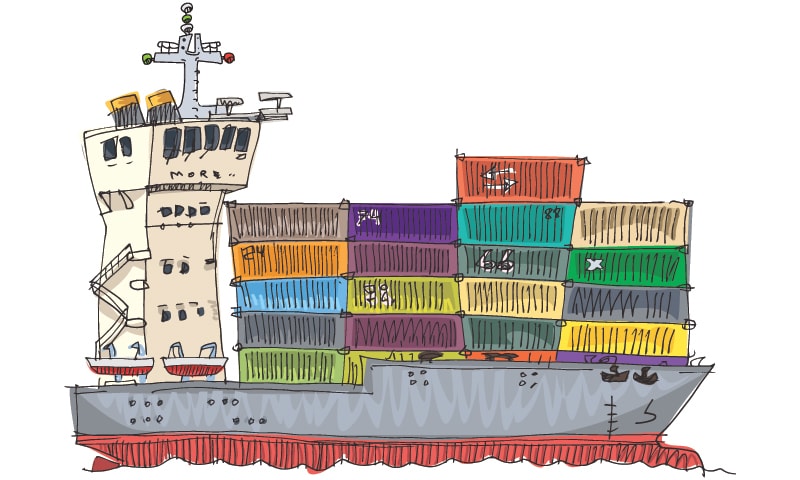

Amongst what is sourced from India are raw materials and intermediate goods that are used by Pakistan’s key export sector — textiles. An analysis of numbers from International Trade Centre (ITC) indicates that cotton has been amongst the top import items since 2007 and accounted for a third of Pakistan’s total cotton imports in 2018.

As the illustration shows, dyes (textiles and others), cotton yarn and textile spinning machines, all used by Pakistan’s vital textile industry, constitute a hefty portion of the country’s total imports of those goods at the HS Code 6-digit level.

Should Pakistan be growing cotton rather than importing from India? Most definitely. Similarly, cotton yarn and dyes are products that should be manufactured domestically irrespective of the trade ban.

However, these arguments have been made since time immemorial. It does not change the ground reality that in the short-to-medium term at least the cost of doing business will rise because of the trade ban.

As an importer and small-scale manufacturer pointed out, switching over to alternatives requires experiments. For example, in case of dyes the manufacturer would have to test strength, tone, particle size, level of dispersion in water and so on before finalising a new vendor. Many would opt to remain with Indian suppliers even if they condemn its actions in India-held Kashmir.

Despite the picture painted by the numbers, various business leaders and association representatives downplay the impact of the trade ban, holding the view that geo-political issues supersede economic interests.

Calling the government’s action a political and principled, Pakistan-India CEOs’ Business Forum Founder Amin Hashwani went on to speak about honour amongst thieves.

“Even smuggling from India under the guise of the Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade may reduce because even thieves have rules,” he said.

The export impact

In terms of numbers, Pakistan’s exports to India are negligible and dispersed over several tariff lines. Not only para-tariffs and non-tariff barriers made it difficult to export what was permitted, at times anti-Pakistan nationalist sentiments made Indians opt for local alternatives.

However, as Mr Hashwani pointed out, dry dates from Sindh are exported primarily to India.

While the dollar value of exports is not significant, it does affect that section of date growers and exporters substantially.

In 2018, India accounted for 31pc of Pakistan’s cement exports. An analyst covering the cement sector asserted that Pakistan-India relations have already impacted cement players, especially those that are situated near the border.

Solidarity with Kashmiris may be the common rhetoric among all businessmen. But when it comes to business interests, especially of small-scale firms that may be unable to shift vendors or absorb extra costs, commercial interests may supplant patriotism. Those who have the scale and the availability of alternate avenues can afford nationalistic sentiments.

Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, August 19th, 2019